writing is an inherently dignified human activity

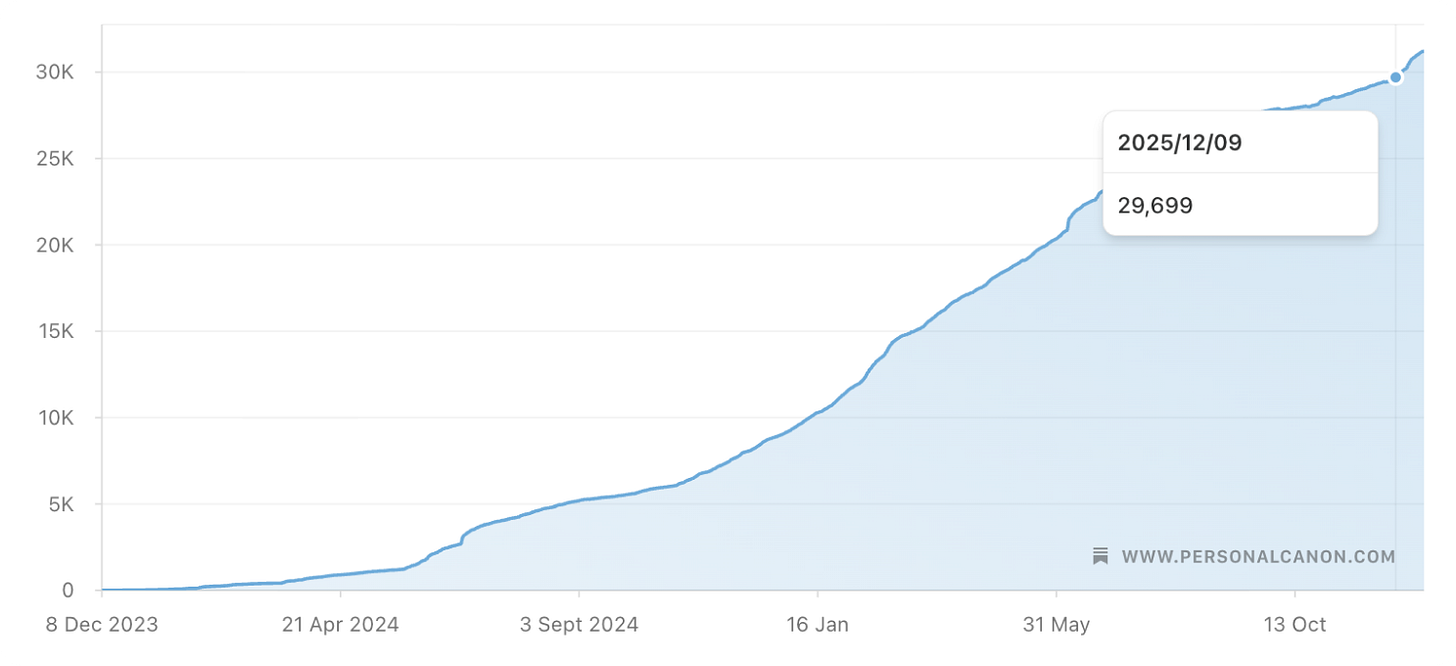

the case for starting your own newsletter ✦ and reflections on 2 years, 52 posts, and 31,000 subscribers

In 2023, after several years of failed new year’s resolutions, I decided to try something new. My annual attempts to “write more” never seemed to last longer than a month; I began to fear that I was someone incapable of finishing projects, of executing on ideas.

But in early December, I seized upon a sudden, capricious urge to start a newsletter—drafting my first post on a Wednesday evening after work—and once I’d sent my first email, it was easier to continue writing. That was my first strategy: to begin my resolutions in December, unburdened by the cumbersome weight of the new year.

A few weeks later, while drafting the usual new year’s resolutions—scroll less, read more, call my parents every week—I came up with a second strategy: to offer myself the generous buffer of a two-year goal, instead of compressing all the changes I wanted to make into 12 months. As I wrote in my journal,

What…might be possible in 2 years? What if I seriously, very very very seriously, commit to my literary practice?…

It typically takes me 2 years of unrelenting but highly diverting & pleasurable obsession to become really, really good at something & make it a part of my life. To turn it into something that seems to come naturally to me…so that’s what I’m doing now.

I decided I would write one newsletter a week, and do it for two years before quitting. That meant 2 years of consistent writing, even if no one was reading. As my longtime subscribers know, the weekly schedule fell apart almost immediately; after the first 3 months, I went from one newsletter a week to one every 2 weeks, or longer. (Earlier this year, when I was grieving a friend’s death and a breakup, I didn’t post anything for 5 weeks.)

But I kept on writing. On December 9, two years after sending my first newsletter, I was quoted in Jay Caspian Kang’s weekly column for the New Yorker, where he described me as a writer “who publishes heady critical essays on Substack.”

It was an unexpected and deeply gratifying way to celebrate two years of writing personal canon. And in a year where writers are justifiably distressed by the dawn of a post-literate society, a brain rot without borders, and ChatGPT-induced cognitive decline, the success of this newsletter seems especially improbable. Concretely: I write a newsletter about literary criticism with over 30,000 readers, who have chosen to receive 4,000 to 10,000–word emails discussing books by independent presses (including Fitzcarraldo, New Directions, NYRB Classics, And Other Stories) and university presses (including MIT Press and Yale University Press), alongside literary fiction and nonfiction from Big 5 publishers.

Writing this newsletter has convinced me that there is an immense hunger for intellectually stimulating, challenging content—in spite of the internet’s tendency to elevate clickbait and slop. The 3 most popular newsletters I’ve ever published are about:

Research as a leisure activity (and why it’s worth pursuing outside of academia)

Close readings of essays published in New Yorker, Bookforum, n+1, and Harper’s

The case for reading Marcel Proust’s 3,000-page modernist novel, In Search of Lost Time1

These are all subjects that, according to conventional wisdom, should only have a niche audience. But it turns out that the audience for this writing—alongside my other posts on self-deception, conceptual metaphors, and the philosophy of aspiration—is much larger than I expected.

And my readers—generous, intelligent, discursive, insightful—have also surprised me. They include literary critics and English professors, as you might expect, but also venture capitalists, startup founders, quantitative researchers. People have subscribed after seeing my newsletter featured on the front page of Hacker News; the literary magazine Lapham’s Quarterly’s link roundups; the economics blog Marginal Revolution; and the Indonesian-Irish influencer Moya Mawhinney’s YouTube channel. And many of my readers are young! Despite all the handwringing about Gen Z’s screentime, many of them are collectively ditching their phones for book clubs and literary readings instead.

Writing this newsletter has given me an “appealingly contrarian” perspective, as Kang observed in his column, on how the internet has influenced our intellectual lives. We may be living through a decline in literacy and the death of the humanities—but every time I send a newsletter out into the world, I hear from people who are committed to taking art, literature and ideas seriously, despite what our phones are doing to our attention spans.

After 2 years, I’m convinced that reading and writing are the most dignified and worthy activities that anyone can do—and, in fact, are activities that everyone should do. Below, some reflections on:

How writing can change your intellectual and social life—and even your sense of self

In defense of performative reading (and how to turn the literacy crisis around)

Advice and recommendations for starting your own newsletter

I wrote about my first year of newsletter writing in—

How to change your life (by writing on the internet)

When I began writing this newsletter, I was 29, living in San Francisco, and working for the software company Notion. At the time, these seemed like inauspicious conditions for a writing practice—I had this vague, barely-conscious belief that writers were Ivy League humanities majors who, upon moving to NYC after graduation, immediately landed a journalism or media job—thanks to a coveted magazine internship the summer before, or well-connected writer friends. I had none of these things. Surely this meant that I couldn’t write?

Two years later, I’m 31, living in London, and still working in tech—at a climate startup called Watershed.2 I’ve written 51 newsletters, along with book reviews for The Atlantic, ArtReview, Asterisk, Asymptote, The Believer, the Cleveland Review of Books, and the LA Review of Books.3 I do all this on weekends, Monday mornings, Thursday evenings. In cafés, in bed, in the kitchen while the oven is preheating, in a conference room ten minutes before my first meeting.

You don’t need to quit your day job (or have a “dream job”)

I used to think that I didn’t have enough time to write unless I had an entire day free. But it turns out that you can steal away little slivers of time from an ordinary day, and devote those miscellaneous seconds to writing, and get a lot of work done.

My best writing (and my best thinking) happens when I have hours to sprawl out and shepherd loose ideas into a more coherent shape. But on days when I didn’t have that, I had 5 minutes before work to type out an outline in the Notes app. Or 15 minutes after lunch to line-edit a paragraph. If a friend was running late to dinner, I’d reread drafts on my phone, wincing at the clumsiest sentences, and bolding the parts I wanted to edit later that evening.

After years of wanting to write—and not doing so—I was taken aback by how by how little time it took to finish a newsletter. It turns out, as the technologist Nabeel S. Qureshi wrote, that

Things don’t actually take much time (as measured by a stopwatch); resistance/procrastination does…If no urgency exists, impose some.

My heroically short-lived attempt to post weekly meant that I was always desperate for a newsletter idea. And once I had the idea, I couldn’t be picky—I had to finish it immediately before the next week began. My early newsletters were crudely written, underdeveloped, amateurish. But as Ira Glass, the producer of the renowned radio show This American Life, famously observed:

For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not…your work disappoints you. You gotta know it’s normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week you will finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions.

Two months into writing my newsletter, I sent the first everything i read newsletter (which included capsule reviews of books, films, essays and poems) because I had no other ideas. And my weekly post was overdue. I wrote it in bed on a Tuesday evening, laptop propped up on my knees for three hours, and sent it during lunch the next day.

It became a recurring series, and the blithely informal title—which I chose purely because I had no other ideas—has since inspired several other literary Substacks and Instagram accounts.

How it started; how it’s going—

Do what you really want to do now!

Early on, whenever I felt discouraged by my mediocre writing, I would cheer myself up like this. First, I would find a newsletter or blog I admired: stylish, well-written, distinctive in voice and approach. (And popular: they often had thousands of readers.)

Then, I would go into the newsletter’s archives and scroll down to the very first post I could find. It was always more raw, unpolished, and amateurish than the writing I was familiar with. I can’t describe how reassuring this was! I could see how people had become—through persistent and publicly-observable attempts—the writers that I knew and loved.

It does take time to write, and to write well—but that time is measured over months, if not years. I don’t write every day, although I’d like to. But I write almost every day. And I finish my projects. Before, I would put off projects until I was ready—when I had finally attained, in the words of the film critic A.O. Scott, a “state of perfectly cultivated being…once you’ve read everything, then at last you can begin.”

But it’s doing the work that makes you ready. You become capable of writing an essay by writing the essay. You become capable of writing a novel by writing the novel.4 And you can start doing the work now: with a day job, with a 50-minute commute on the overground, without an MFA (or even with an MFA that didn’t fully prepare you—because even an excellent education requires that the education be used, at first clumsily, and then more fluidly, to become truly useful).5

People like to daydream about the writing they’ll do when things are perfect. When they have an easier job, when they get accepted into a residency, when they’ve saved enough money to take a sabbatical. In tech, people will joke that they’re waiting for a life-changing IPO—and then they’ll start writing, painting, making music.

But taking your literary, artistic, and intellectual ambitions seriously—and carving out time for them, in between work, commuting, childcare, stakeholder management, grocery shopping—is one of the most satisfying things you can do. And the reality is that if you don’t start your work now, you won’t have the discipline to do it later. There may be a time in your life when everything is easier. But you need to start closing the gap between your taste and your execution today. Read the book that you’re afraid you can’t understand yet. Write the essay you’re not sure you can pull off. How else will you become capable of it?

Thought daughters, performative reading, and how to turn the literacy crisis around

Writing this newsletter has made me particularly invested in two specific discourses about how people read—and write—today:

The performative reader. I still can’t tell how often this man (or woman, or they/them) is observed in real life. But in 2025, the idea of a performative reader is highly visible and frequently ridiculed online. “The presumption” behind the meme, as the journalist Alaina Demopoulos wrote in The Guardian, is that people reading conspicuously identifiable books in public are “performing for passersby, signaling they have the taste and attention span to pick up a physical book instead of putting in AirPods.”

Though in 2025 the performative reader is assumed to be a man, closely associated with this stereotype is the moral panic around hot girls reading and writing in public. See: the glut of celebrity book clubs in 2024. Also see: people mortally offended that charli xcx, the PC Music–affiliated pop star, had the temerity to start writing on Substack. (Are musical performers not allowed to perform any other virtues?)

The literacy crisis. “We used to read things in this country,” Noah McCormack lamented recently (and as publisher of The Baffler, it’s an existential threat to his vocation if we stop). But now? In 2024, a few months after I began writing personal canon, the theologian and educator Adam Kotsko described a “confluence of forces that are depriving students of the skills needed to meaningfully engage” with books:

For most of my career, I assigned around 30 pages of reading per class meeting as a baseline expectation…Now students are intimidated by anything over 10 pages and seem to walk away from readings of as little as 20 pages with no real understanding…Anecdotally, I have literally never met a professor who did not share my experience.

It’s only gotten worse as students have started using LLMs for “reading” and “writing” texts. Earlier this year, the poet Meghan O'Rourke and philosopher Anastasia Berg wrote about the impact that LLMs are having on basic literacy and comprehension (they teach creative writing and philosophy, respectively, at two of the most academically rigorous universities in the country).

Taken together, these crises suggest that we are increasingly fetishizing and aestheticizing the ability to read, at a time when this capacity seems most threatened. Universal literacy is one of the most hard-won victories of educators and activists of the past few centuries; the right to access written language, scholarship, and formal education was highly contested and has only been taken for granted in recent memory.6

And literacy involves more than just accessing what others have written, but having the agency to actually contribute back to the written word. To articulate—from your own subjective, distinctive, and highly contingent experience—what you think about other people’s ideas. To be a participant in the world.

One of the curious things about the handwringing around the “performative reader” is how paranoid it is. It presumes that people reading in public are doing it for the wrong reasons, which is to say: they are reading because they want to be seen as readers, not because they have a genuine, unforced interest in reading.

Reading as lifestyle (non-derogatory)

The panic around the “performative reader,” as the writer and The Yale Review editor Jack Hanson noted, can be characterized as

the collective noticing of the presumably young man who reads books in public, perhaps while also drinking wine or smoking, wearing some kind of hip accessory, in the hope of getting attention and, ultimately, laid.

First of all: don’t we want young people to get laid? (The loneliness crisis is also a crisis of sexual intimacy, as the writer Magdalene J. Taylor has observed.) But also, Hanson writes:

There is something really odious about the adolescent impulse to point out someone else’s everyday, ordinary social ambition, and to condemn them for it. Someone wants favorable attention? Who doesn’t?…If some men do read in public in hopes of sexual conquest, staring blankly, turning pages automatically, positioning the cover just so…Well, I think we can all agree that it’s pretty low in the ranks offenses carried out for that purpose.

And there is something not just odious, but incoherent about the assumption that performing literary ambition is inherently wrong or fake. The original function of the word “performative,” Hanson writes,

was originally intended to describe how apparently artificial practices have a constructive social function: performances, though in some sense contingent or even arbitrary, make real things happen…

Nowhere is it suggested that a performative act is fake; to the contrary, it is a central component in the production of our social reality.7

When the term was coined in twentieth-century social theory, it was, Hanson suggests, “a genuine advance in modern human self-understanding.” It helped people become conscious of how they could, through their behaviors, construct new selfs and new societies. But the colloquial use of performativity “doesn’t describe our freedom to remake our shared life, it reveals our falseness and our shame.”

But what if we reclaimed this idea of falseness, of doing something for the wrong reasons?

In Aspiration: The Agency of Becoming, the philosopher Agnes Callard describes a hypothetical music teacher who is frustrated that her students are taking her class for the “wrong reasons.” The right reason would be that they already understand the intrinsic, inherent value of music. But they don’t yet. That’s why they’re taking her class. “Consider,” Callard writes,

…what kind of thinking motivates a good student to force herself to listen to a symphony when she feels herself dozing off:…perhaps she conjures up a romanticized image of her future, musical self, such as that of entering the warm light of a concert hall on a snowy evening. Someone who already valued music wouldn’t need to motivate herself in any of these ways. She wouldn’t have to try so hard.

But Callard doesn’t think that trying condemns someone to failure. And wanting to appreciate music—or literature—or art—for the wrong reasons does not prevent someone from accessing the right reasons, eventually. In the student’s case, Callard suggests that

“Bad” reasons are how she moves herself forward, all the while seeing them as bad, which is to say, as placeholders for the “real” reason.

The real reason to read literature is that it is an autotelic activity—it has inherent, intrinsic value, even if it doesn’t make you more intelligent, attractive, cultured, respected. But it’s still meaningful to read for the wrong reasons.

And positive societal outcomes can occur even if someone is, let’s say, buying books for the “wrong reasons.” The performative reader who buys a book from Transit Press (an independent, nonprofit publisher based in Berkeley) just to post it on Instagram? They’re still supporting a publisher responsible for bringing Nobel Prize–winning literature to the United States.8

Literary consumption is different than other forms of conspicuous consumption. Books are often cheaper than tasting menus, international travel, and designer fashion. Let the girls (and guys) romanticize their reading lives a little! If a sultry Sunday morning selfie (with a copy of the NYRB conspicuously present next to a matcha latte) is what gets more people to read literary criticism, why not celebrate it?

Surely it’s better to make conspicuous book and magazine consumption into an aspirational activity—it’s better than recurring Klarna payments for poorly made clothing. As the writer and brand marketer Ochuko Akpovbovbo argued in her newsletter last year:

Reading is hot, good literary taste should be celebrated, and people aren’t reading nearly enough for ‘hyper consumerism’ to be…attached to this conversation.

The aestheticization of literary taste can help turn reading more into an aspirational project. This seems like an unambiguous social good. Newsletters like postcards by elle (over 100,000 subscribers) and Instead of Doomscrolling (over 300,000 subscribers) testify to the immense power of organizing the inchoate aspirations of young people into a focused, directed desire to read seriously and take your intellectual life seriously. Both have an accessible, informal tone—which they use to recommend essays from esteemed publications like The Paris Review, The Hedgehog Review, and Aeon, as well as books by writers like Ali Smith and Edith Wharton. The women behind these newsletters are helping to create a culture where knowing what to read is just as desirable (if not more desirable) than knowing what to buy.

Write for yourself (in order to think for yourself)

Human behavior is imitative. We read because the people we admire do so. We begin to admire the writers that have altered our ways of thinking. And often, we seek to imitate our new idols—by beginning to write ourselves.

This desire to write is, I think, something to cherish. I often come across articles that imply that writing badly is somehow offensive to others—that’s unnecessary, or even selfish, to inflict your mediocre work on the world. But because I see reading as an essential human behavior—an infinitely precious capacity that everyone should practice—I accord the same dignity to writing.

One’s initial ability is, in some senses, irrelevant. In a newsletter from earlier this year, the cultural critic rayne fisher-quann suggested that choosing to write is a lot like choosing to walk:

It’s rarely the most popular, the most effective, or the most efficient way of getting to your destination. I don’t always want to do it, and it’s not always technically enjoyable; sometimes it’s boring or slow, sometimes it’s tiring and pointless…Nonetheless, I always feel worse in my body and mind when I avoid it for too long, and it’s a loss that feels greater than just the quantifiable enumeration of calories I didn’t burn or sunlight I didn’t see.…When you choose to walk, you choose not to pursue immediate gratification or even comfort but simply to expand the number of things that might happen to you. Walking invests in the potentiality of your experience with almost no promise of tangible reward at all, which is something like being alive.

If you’re exclusively interested in the output of writing, then it makes sense to chastise people who write badly—because the output seems to be inferior to what others are capable of producing. But if you think of writing as a process, then you understand that writing badly is the only way to begin writing well, and the output isn’t the piece—it’s the mind that labored earnestly to produce the piece.

The labor is not just in producing the writing; it is in becoming the mind that has an idea that is worth putting into writing, and then striving to convey it in the best possible form. As Fisher-Quann observes,

An essay is not the process of translating a fully-formed idea into words on a page; it is the process of discovering and testing an idea by challenging it with form, syntax, structure. The friction between idea and ability…[is] the fundamental condition of the writer, and it is precisely through that friction that we discover what it is we actually have to say.

Expressing ideas effectively through writing is not something that people are born being able to do or not do; it’s a muscle that anyone can develop and that anyone can let atrophy.

What do you want your life to look like? What’s the right way to treat other people? Was the film you just saw good or bad, and why? What conditions are necessary for an ethical and equitable society? What’s more valuable than people think it is? What’s less valuable than people think?

To write is to wrestle, very deliberately, with whatever your first instincts are when confronted with these questions. And to take those instincts further—to develop a more sustained, comprehensive point of view and make it concrete.

I used to read other people’s essays and be intimidated by their intellectual virtuosity and confidence. It seemed effortless—how they could invoke particular literary quotations, historical anecdotes, philosophical frameworks and pop-cultural phenomena to support their arguments. But when I began writing, I realized that this performance of effortlessness involved a great deal of effort. Rarely do writers have all this knowledge from the start. Writing is what gives you this knowledge.

When you start writing, that’s when you really start thinking seriously. Only when you finish the piece do you understand what you’re trying to say.

Writing as metamorphic activity

One of the best interviews I listened to this year was with the writer Henrik Karlsson, who—on Jackson Dahl’s Dialectic podcast—suggests that writing is a form of self-cultivation:

The project I’m doing is basically turning myself into a certain type of person who is able to have these thoughts. The essays are…just exhaust from the project. The work is growing emotionally and intellectually in such a way, and just going out into the world, talking to people, reading, looking at things, and becoming the kind of mind that can have these thoughts. That’s the real work.

Karlsson’s description reminded me of a framework that the longtime blogger and technologist Venkatesh Rao proposed last year. In “Striver, Seeker, Icon, Leader,” Rao suggested that there are 2 ways to write. You can write instrumentally, and “try to change the world in predictable ways, while acquiring some sort of legible extrinsic reward…[like] esteem or money.” But you can also write metamorphically: to transform yourself (metamorphosis).

Metamorphic words…attempt to change the author in unpredictable ways, which you can think of as an intrinsic reward of sorts…

If you don’t like, or are bored with, who you are right now, whether as a writer, or more generally as a person, you can write yourself into an unpredictable new version. It’s a kind of disruptive self-authorship lottery…You can achieve metamorphic effects with other media too, but writing is particularly good for it.9

Metamorphic writing can be private; the diaries and journals of famous writers, like Franz Kafka and Virginia Woolf, can often be read as künstlerromans: they show how Kafka became Kafka, one page at a time. (In one entry, he writes, as if to remind himself: “Hold fast to the diary from today on! Write regularly! Don't give up! Even if no salvation comes, I want to be worthy of it at every moment.”)

But metamorphic writing can also be public. I’m touched by writing that frankly displays the writer’s aspirations—to think more clearly, to behave more ethically, to live with greater integrity. Writing can be a way of forming these aspirations and holding yourself accountable to them—until the traits which are affected, which are performed, become natural to you.

And when it comes to the work of writing—which is also the work of thinking, reading, and living—I’ll say this. As a human being, intellectual discovery and gratification are your birthright. Nothing is more worthy, and more self-actualizing, than taking your interests seriously and pursuing them as far as you can go.

No, it is not too late to start a newsletter

If you’ve made it this far, then please consider this your invitation to take your intellectual, artistic and literary life seriously. And if that ideal life involves writing a newsletter, here are some of my favorite resources:

If it feels too frivolous to write. Begin by reading the writer and essayist Charlotte Shane’s profoundly insightful newsletter deconstructing creative angst:

Here’s a question for everyone who writes, paints, composes, etc., and is haunted by a sense that they’re wrong (bad, selfish, irresponsible) for doing so: if you give up your songs, your art, your poems, what will you replace them with? Where does that energy go? Is writing or art-making in the top five most frivolous things you do?…What good things happen when you stop? What good things are prevented if you persist?

Shane and Jo Livingstone also co-host the Reading Writers podcast, where they transmit their deep love of reading—with guests like Tony Tulathimutte, Torrey Peters, Marlowe Granados and Sarah Thankam Mathews.

If you don’t have a style yet. Not a problem, as the art director Roman Muradov (much-admired, much-imitated) observes:

Style is the sum of your shortcomings. You copy as many artists as you can, and you copy them wrong, then put a lot of thought and time into analyzing their work (as well as your failed copies), and within those missteps is probably where you’ll find your style.

If you want to write (without succumbing to trivial hot takes and hype). kate wagner is surely one of the internet’s most iconic writers, capable of both memetic humor (on her tumblr McMansion Hell) and engrossing criticism (for The Nation, the NY Review of Architecture, and others). She also has an excellent newsletter, and her essay on how to write essays has great advice on choosing a subject, writing what you want, and avoiding ephemeral hot takes.

If you don’t like disclosing too much about your personal life. Conversational, first-person writing performs exceptionally well on Substack. But this doesn’t mean you have to be overly confessional! The literary critic Merve Emre offers a few alternate approaches. One, as she wrote about for The New York Review of Books, is the familiar essay:

The familiar essay seldom treated the author as its object of interest. Rather, familiarity concerned the relationship triangulated between the essay’s writer and its reader—a relationship between friends. Always, this friendship was mediated by the presence of an object to which the writer had committed her powers of perception and analysis, and, through it, secured her reader’s interest: a novel or a painting, a historic figure such as Cato, a creature such as a moth.

The other approach, as Emre suggests in an interview with Sara Fredman, is “relentless sublimation”:

You don’t have to write an essay about your marriage and your divorce. You can just write a piece of criticism that’s about a book like [Sarah Manguso’s] Liars, and you can betray so much about yourself and still not be exposing or betraying others.

If you’re trying to decide how often to post. There are 2 strategies, broadly speaking. I began by posting as often as I could (sending one newsletter a week for the first 3 months) and now send the occasional, high-effort email once or twice a month. They both work, in different ways:

Post as often as you can. It’s the “secret of blogging,” the journalist Max Read observed, and a central part of the success of figures like Matthew Yglesias: “The single most important thing you can do is post regularly and never stop.” In software development, this is similar to “release early, release often.” You can think of this approach, Venkatesh Rao suggested, as the investment strategy of dollar cost averaging, applied to content creation:

If a post happens to say the right thing at the right time, it will go viral. If not, it won’t. All I need to do is to keep releasing…It’s mostly about averaging across risk/opportunity exposure events, in an environment that you cannot model well.

Post rarely, but do exceptional work. On YouTube, the foremost practitioner of this strategy is Natalie Wynn. Most channels upload videos weekly; Wynn posts 1–2 video essays a year on ContraPoints. Henrik Karlsson, who writes one of my favorite newsletters, has observed that “When I have a slower publishing cadence my blog grows faster”:

When I started writing online, the advice I got was to publish frequently and not overthink any single piece…I’ve now written 37 blog posts and I no longer think this is true. Each time I’ve given in to my impulse to “optimize” a piece it has performed massively better (in terms of how much it’s been read, how many subscribers it’s generated, and, most importantly, the number of interesting people brought into my world).

It’s worth nothing that my 3rd most popular post, no one told me about proust, took 18 hours to write.

And the resources I shared in my one-year anniversary newsletter are still valuable—especially Max Read’s advice after 3 years of writing a newsletter; M. E. Rothwell on how to grow on Substack; and Adam Mastroianni’s argument against the slop school of internet success.

And if you have any other questions, leave a comment below—I’ll do my best to answer them all!

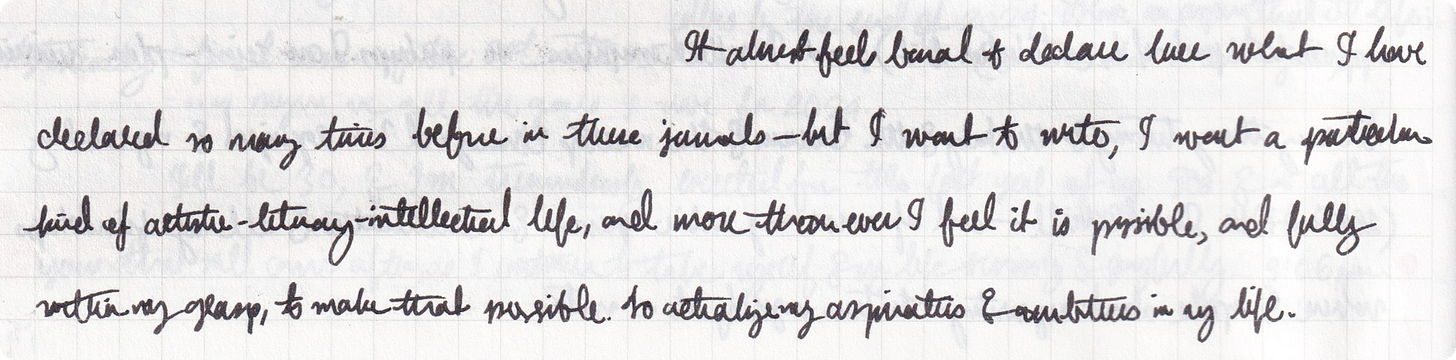

While drafting this newsletter, I went back to some of my old notebook entries, from the earliest weeks of personal canon. In one, written on my 29th birthday, I reflected on the life I wanted to have in the coming decade:

It almost feels banal to declare here what I have declared so many times before…but I want to write, I want a particular kind of artistic–literary–intellectual life, and more than ever I feel it is possible, and fully within my grasp, to make that possible.

For most of my twenties, I was afraid to begin writing. I believed, with the curiously ingrained pessimism of youth, that I was—somehow—already too old to begin. Because I hadn’t written anything of substance yet, I believed that I never would.

But as the designer, art director, and technologist Eric Hu once tweeted,

[A] big regret is saying to myself back in 2019, “I want to do this thing but I feel too old to start and it’s going to take five years.”

Those five years went by like nothing. I’m even older than I was and that yearning never left. Glad to start now but don’t make the same mistake.10

I’m turning 32 in a few days. And I feel more optimistic and energized than I did in my early twenties, when I foolishly believed that it was too late to become someone new. Every morning I wake up eager for the next book I’ll read, the next essay I’ll write.

“Doing as much as you can every day,” the technologist Nabeel S. Qureshi wrote, “is a form of life extension.” If you want to feel young for the rest of your life, start writing.

Four recent favorites

I brake for <br> tags ✦✧ The year’s best personal essays ✦✧ Your favorite newsletter’s (latest) favorite newsletters ✦✧ Touching, feeling, cataloguing, shopping

I brake for <br> tags ✦

I don’t have a car (I’ve spent my entire life trying to avoid cars) but these bumper stickers—designed by Bri Griffin for the digital art organization Rhizome—could easily work on a Nalgene or laptop!

The year’s best personal essays ✦

In 2025, no position is more contrarian—especially for a writer—than staking out the position that things might be good, actually. In a recent newsletter, the writer Geoffrey Mak, who wrote the memoir Mean Boys and is an editor-at-large at Spike, suggests that

The personal essay is where the most formal innovation is happening today in American prose…For those of you who still believe in the avant-garde, it’s possible that today’s literary modernism is to be found in the personal essay.

Mak offers up 6 essays as proof: by Catherine Lacey, Yiyun Li, McKenzie Wark, and others.

Your favorite newsletter’s (latest) favorite newsletter ✦

I love writing on Substack; but I especially love reading on Substack—I continue to discover new, excellent literary newsletters every month.

I’ve been telling a lot of my friends about Dhimmi Monde lately, a newsletter that publishes short, funny reviews of books from small and independent presses. John W Schneider’s review of Sonya Walger’s novel Lion, for example, has the cheeky title “With Women It’s Always One Thing After Another.” It’s an excellent close read of a single sentence of Walger’s novel, and the contemporary literary novel’s fascination with lists, and the paratactic phenomenon of the fragment novel. And if you’ve ever felt that I run a little…overlong…then Dhimmi Monde’s newsletters are admirably succinct: a little over ten paragraphs, and then you’re done. Brevity is an excellent skill. I wish I had it.

Another person whose brevity I envy: Michael Patrick Brady, who writes reviews for the WSJ and Washington Post, but also on his excellent Substack newsletter, These things, not others. His year in books is organized under appealingly opinionated headings, from “Highly recommended” to “Proceed with caution,” ending with “Actively dissuade people from reading it.”

My favorite micro-reviews:

Highly recommended: The Lesbian Body by Monique Wittig (Winter Editions, November). Desire articulated in its rawest, most uncut state.

Worth checking out: How To Be Avant-Garde: Modern Artists and the Quest to End Art by Morgan Falconer (W.W. Norton, February). Can fascists and anarchists make good art? Maybe. But don’t let your guard down.

Worth checking out: Between Two Rivers: Ancient Mesopotamia and the Birth of History by Moudhy Al-Rashid (August 12, W.W. Norton). It’s worth considering how resilient the tablet form factor has been throughout human history—ancient Mesopotamians, they’re just like us!

Skip it: Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season by John Gregory Dunne (McNally Editions, July). There’s a reason it’s back in print now (trying to get some heat from being Didion-adjacent) and a reason it was out of print for so long (it’s really bad).

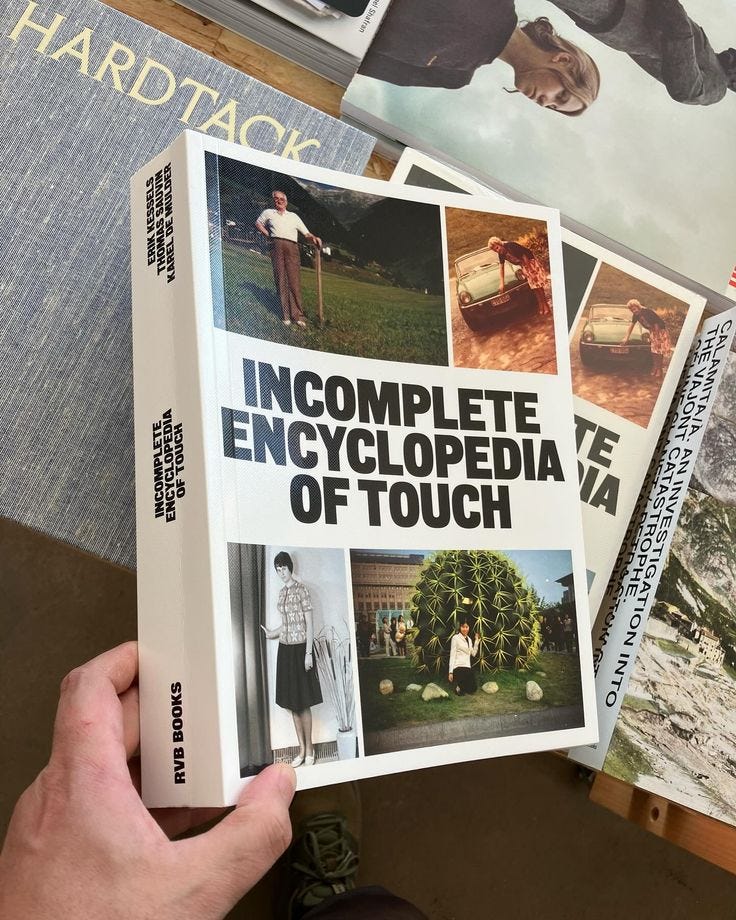

Touching, feeling, cataloguing, shopping ✦

I have a particular weakness for art books with profoundly evocative titles, and the Incomplete Encyclopedia of Touch—containing 1,919 photos selected by Erik Kessels, Thomas Sauvin and Karel de Mulder—is especially good. At €60 a copy, that’s 3 eurocents an image.

Distilled from over 15.000 family albums, [the book] archives the human desire to put a hand on things. Whether it’s cars, boats, animals, trees, fridges, bridges, bushes, fellow humans or even their graves—everything that can be touched will be touched…[which] provokes questions about the underlying motivations behind this universal pictorial behavior. Do we seek connection? Do we claim ownership? Or do we just want to measure ourselves to the objects of our world?

Need a little more encouragement to take on the daunting (but profoundly rewarding) project of reading Proust? Try reading Nabeel S. Qureshi’s Proust post, or Jonah Weiner—one-half of the cult-favorite fashion newsletter, Blackbird Spyplane—on Proust:

Come work with me! Or rather, come post in the same corporate Slack channel I’m in, which may also include working with me directly. Watershed has offices in SF, NYC, London (where I work as a product designer) and Mexico City. If you’re particularly invested in reading IPCC reports and whitepapers about energy transition, you can also look at the company’s recommended reading list.

It’s always difficult to balance a day job with other artistic–intellectual–creative–community pursuits, but I feel very lucky to have a day job that is personally meaningful. Alongside the literacy crisis, the climate crisis is probably the issue I care about most.

I’m working my way through the alphabet, one magazine at a time.

As someone who finds a 5,000 essay disorientingly difficult to write, I am thoroughly impressed by all the novelists I know—and have met, for the most part, through this newsletter—who have multiple novel drafts behind them. Finishing an an entire book is an enormous accomplishment, whether it gets published or not.

I don’t want to elide all the difficulties of carving out time for writing—especially when you have caretaking responsibilities, like elderly parents or children. (I don’t.)

And day jobs vary enormously in terms of how well they facilitate an independent intellectual–literary–artistic life. I’m an office worker, and I have excellent working conditions and pay relative to my city’s cost of living. It’s not easy to work 40 hours a week, commute 8 hours, and still carve out time for my writing. But it would be much harder if those 40 hours barely paid my rent and financial precarity was a real concern.

I don’t want to say that anyone, with any day job, can put a lot of time into their writing. But I do think everyone deserves to. And there more than a few day jobs that can still afford a meaningful intellectual life—you don’t have to be in academia, or publishing, or the arts…especially since the working conditions of these fields sometimes make it harder to live the life of the mind.

I spent a lot of my twenties fretting that I couldn’t do the work I wanted to unless I went to grad school, or worked in a different industry. But in the last few years, my philosophy has been: Why not cultivate the life of the mind—inside the life I’m already living?

You still can’t take basic education and literacy for granted in many parts of the world, which is an enormous injustice—but it’s beyond the scope of this newsletter to get into it. (It’s also not my area of expertise.)

Thank you to H Nieto-Friga for pointing me towards Hanson’s “Performativity!” essay.

In the spring, Transit Press was informed that their $40k grant from the National Endowment of the Arts would be terminated. The reason, according to the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), was that their work did not fit President Trump’s “new priorities.” But the loss of NEA funding—which affects many other independent publishers—will have a direct impact on the number of books that Transit is able to publish in the next few years.

Transit is the American publisher for the Nobel laureate Jon Fosse, as well as the French writer Laurent Mauvignier (who won the Prix Goncourt this year). They also publish some of America’s most innovative contemporary writers, like Kate Zambreno and Namwali Serpell.

If you’re a Silicon Valley technologist who loves literature and the Bay Area…and you have RSUs or ISOs in a startup that’s having a liquidity event soon…then consider making a donation to Transit. It’s one of the highest-ROI donations you can make, if you’re invested in American and contemporary literary culture.

I also think it’s a particularly effective form of psychotherapy; for more on this, see Louise DeSalvo’s Writing as a Way of Healing, which uses insights from James W. Pennebaker’s psychology research, as well as DeSalvo’s own work as a Virginia Woolf scholar and longtime writing professor at Hunter College, to describe how writing about traumatic experiences can help people recover from them.

Here’s another tweet that essentially says in 56 words what it took me thousands of words to explain:

a mistake that cost me 5 years: thinking preparation was progress. reading every book. taking every course. planning every detail. meanwhile, someone dumber than me started badly and figured it out. preparation feels productive but it’s often just fear dressed up as strategy. you learn to swim by getting in the water, not by studying water.

What a divine article to read just as I approach a new year and the age of 30. I've been wanting to write for so long and have suffered from various reasons or forms of procrastination such as: "what if no one reads my writing?" "what if I have nothing valuable to say?" and "what if my friends read my writing and I self-censor my words from fear of exposure?"

Anyway, off to publish my second newsletter feeling much better about all of this. Thank you thank you for another thoughtful piece.

Your approach of encouraging reading and writing as a way to facilitate metamorphosis regardless of motivation is so important and has struck me deeply - thank you for sending this just before the New Year!