don't deceive yourself

on delusional fantasies and self-respect ✦ feat. Elsa Morante, Didion, Flaubert and Tolstoy

I’ve never been paranoid about other people lying to me. Most people, I’d like to think, mean well. They have an instinct for generosity. They aspire to be good, to be worthy of other people’s respect. The little white lies of interpersonal life—the friend who texts to cancel plans and says, Something came up at work, sorry! instead of revealing that she’d rather sleep early than meet me—seem inconsequential, essentially harmless. Lie to me if you’d like! I trust you to choose the lie that benefits both of us.

What disturbs me, what keeps me up at night, is how I lie to myself. “Self-deception,” Joan Didion wrote in 1961, “remains the most difficult deception”:

The charms that work on others count for nothing in that devastatingly well-lit back alley where one keeps assignations with oneself: no winning smiles will do here, no prettily drawn lists of good intentions. With the desperate agility of a crooked faro dealer…one shuffles flashily but in vain through one’s marked cards—the kindness done for the wrong reason, the apparent triumph which had involved no real effort, the seemingly heroic act into which one had been shamed. The dismal fact is that self-respect has nothing to do with the approval of others—who are, after all, deceived easily enough.

But how do you resist this kind of danger, when—by definition—the deceived self can’t even identify the lie? I’m trying to teach myself how to see what I don’t know about myself; to find the failures that my ego tries to ignore.

I read literature—fiction, essays and memoirs—to understand how others have deceived themselves, and how they escaped. And I read nonfiction to confront my beliefs, challenge them, change them.

In this post — Joan Didion, “On Self-Respect” ✦ Elsa Morante, Lies and Sorcery ✦ Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary ✦ The Philosophy of Deception, edited by Clancy Martin ✦ Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina ✦ Oliver Burkeman, Meditation for Mortals ✦ Aschen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists ✦ Gabriel Winant, “Exit Right”

How to deceive yourself

Let’s say there are 3 forms of self-deception. You can deceive yourself about who you are. You can deceive yourself about the choices you can make—or the choices you’ve already made, and why. And you can deceive yourself about the world you live in.1

Lies and escapist fantasies

Self-deception is the great theme of the novelist, poet, and translator Elsa Morante’s first novel, Lies and Sorcery. Morante was the first woman to win the Strega Prize, a prestigious award for Italian-language literary fiction. The second woman to win, the renowned author and activist Natalia Ginzberg, described Morante as “the greatest writer of our time.” Ginzberg had been one of the first people to read Lies and Sorcery, and as she described later:

I don’t know if I clearly understood its importance and greatness at the time. I only knew that I loved it and that it had been such a long time since I’d read anything that filled me with such vitality and joy…[while the] chapter titles…felt so nineteenth-century…the novel was actually describing our own time and place, our own daily existence with lacerating and painful intensity.

Ginzberg wasn’t alone in her admiration. Italo Calvino described it as a novel that “desperately and successfully penetrates to the bone, exposing the painful condition of humanity.” The Romanian literary critic Georg Lukács praised it as the greatest modern Italian novel he’d read. But when Lies and Sorcery was first translated into English in the 1950s, it was nearly unrecognizable to Morante, with arbitrary omissions that she saw as a “mutilation” of her vision.

But Morante’s masterpiece can now be read in a new, more respectful translation by Jenny McPhee, published by the NYRB Classics last October. (You can buy it here!) I began reading the novel because the short story writer Deborah Eisenberg—who I revere for her precise, devastating portraits of human frailties—wrote a beautiful review of Lies and Sorcery that makes the novel come alive.

Lies and Sorcery begins with a tragedy: Elisa, a young woman living in southern Italy, is living alone after both parents and her guardian have passed away. “In the silence of her sudden solitude,” Eisenberg writes,

She sees that she has lived her life in thrall not only to the lies her parents lived by but also to the progeny of those lies: insubstantial, self-flattering, childish, and consuming fantasies of her own construction.

These consolatory and pleasurable fantasies…have insulated her from painful realities, but only at the cost of leaving her disastrously diminished, arrested, isolated, and all but immobilized. Clearly, she must find her way out of this self-perpetuating prison by disentangling herself from the skeins of deceptions she has inherited and elaborated. “All I desire is to be honest with myself,” she says. But how is she to go about that, debilitated as she is? It takes a great deal of energy and all too much practice to be a person—to yield to reality as it comes at you.

The great problem of the novel, then, is for Elisa to understand how these “consolatory and pleasurable fantasies” have ruined her life, and how she can break free of them. Some of the fault lies with her caretakers. Early on in the novel, Elisa observes that “I was now in possession of the last and most important bequest left to me by my parents—lies.”

But the novel makes clear that you can’t blame your parents for everything! Take the example of Nicola Monaco, a friend of Elisa’s grandfather. Monaco has shaped his life around a particular resentment. “He claimed,” the novel tells us, “his true vocation was singing, but his father…had forced him to study accounting…thereby ruining both his singing career and his life.” But this seems like a convenient story, a self-flattering story, one that lets him avoid responsibility for his life:

Rather than make the effort to become one, Nicola preferred to imagine the great man he could have been. For the slightest immediate pleasure, he would sacrifice all future happiness. According to him, the blame lay with his father, who never encouraged him to study singing…

Elisa’s problem is that she must understand her parents, and the lies and deceptions they have offered her—without surrendering responsibility for her own life, as Monaco has.

“Our parents,” the renowned psychologist Paul Ekman observes, “teach us not to identify their lies.” In an essay for The Philosophy of Deception, edited by Clancy Martin, Ekman first summarizes his experimental research into lie detection. It turns out that, even in high-stakes situations where lies really do matter, that people are quite bad at detecting lies! Is there, Ekman asks, an evolutionary and interpersonal reason for this incompetence?

It might be that the lies are useful for us. “We often want to be misled,” Ekman suggests. “We collude in a lie unwittingly because we have a stake in not knowing the truth.” In Elisa’s case, her parents have lied to her by saying that she is part of a great, tragically heroic lineage—and not a dissolute and declining family. Elisa’s struggle to understand these lies, and escapes them, is what makes Morante’s novel feel so penetrating and painfully familiar.

This theme—indulging in fantasy over reality—shows up in other novels, too. It’s the great weakness of the characters in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary and Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina.

In these novels, reality is legitimately disappointing and unfair! Morante, Flaubert and Tolstoy all show how women are constrained by the particular class structures of their societies (turn of the century Italy; and 19th century France and Russia). But there are better and worse ways to operate in an unfair world. And these novels show how personally damaging it can be to refuse to understand the reality of your world.

In Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, Emma Bovary—singularly pretty, charming, and newly married to a country doctor—first uses novels as an entertaining escape:

She studied descriptions of furnishings, she read Balzac and George Sand, seeking in them the imagined satisfaction of her own desires. She would bring her book with her even to the table, and she would turn the pages while Charles ate and talked to her.2

Soon, her escapism extends to imagining the lives of others, who she imagines to be infinitely wealthier, well-connected, happier. She obsesses over the lives of “ambassadors…the society of duchesses…the motley crowd of literary folk and actresses.” Ordinary people are excluded from her imagination. Instead, she thinks about how richly romantic the lives of these elect are:

Theirs was a life elevated above others, between heaven and earth, among the storm clouds, something sublime. As for the rest of the world, it was lost, without any exact place, as though it did not exist. The closer things were to her, anyway, the more her thoughts shrank from them. Everything that immediately surrounded her — the tiresome countryside, the idiotic petits bourgeois, the mediocrity of life — seemed to her an exception in the world, a particular happenstance in which she was caught, while beyond, as far as the eye could see, extended the immense land of felicity and passion.

Emma becomes increasingly estranged from reality, and convinced that her husband Charles is “obstacle to all happiness, the cause of all misery, and, as it were, the sharp-pointed prong of that complex belt that bound her on all sides.” It’s this belief that makes her susceptible to the flattering advances of other men—she wants so badly to be swept away from her dull life and into a novelistic fantasy.

I had heard, before reading Madame Bovary, that it was a novel about a woman whose adultery ruins her life. But this description makes the novel seem more moralizing than it is! It isn’t Emma’s adultery, precisely, that destroys her. It is Emma’s self-deceptions, her refusal to engage with reality, that makes her affairs so ruinous.

The heroine of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is also caught up in self-deception. Like Emma Bovary, the novels she reads penetrate into her life, and offer her particular fantasies:

Anna…read and understood, but it was unpleasant for her to read, that is, to follow the reflection of other people’s lives. She wanted too much to live herself. When she read about the heroine of the novel taking care of a sick man, she wanted to walk with inaudible steps round the sick man’s room; when she read about a Member of Parliament making a speech, she wanted to make that speech; when she read about how Lady Mary rode to hounds, teasing her sister-in-law and surprising everyone with her courage, she wanted to do it herself. But there was nothing to do, and so, fingering the smooth knife with her small hands, she forced herself to read.3

Anna’s real life feels much smaller, less interesting, compared to her fantasies. There’s a scene where, after meeting the handsome, unmarried Count Aleksey Vronsky for the first time, Anna returns home to her family:

The son, just like the husband, produced in Anna a feeling akin to disappointment. She had imagined him better than he was in reality. She had to descend into reality to enjoy him as he was.

She initially deceives herself about how flattering Vronsky’s interest in her is, and how much excitement it brings into her life:

At first Anna sincerely believed that she was displeased with him for allowing himself to pursue her; but soon after her return from Moscow, having gone to a soirée where she thought she would meet him, and finding that he was not there, she clearly understood from the sadness which came over her that she was deceiving herself, that his pursuit not only was not unpleasant for her but constituted the entire interest of her life.

And it is this all-consuming interest that leads Anna Karenina and Vronsky to fling themselves into love, commit to it, and try to weather the social disapproval and ostracism that follows.

Anna’s struggles were exacerbated by the social milieu she was in—and its very specific norms around appropriate romantic and sexual conduct. But what I find stimulating and challenging about Anna Karenina is how it highlights Anna’s refusal to engage with reality—something I can relate to, even as a 21st century woman. A number of her problems are made worse by not understanding the consequences of pursuing her love affair; or avoiding important conversations with her husband; or not fully accepting the tradeoffs between staying in her marriage or leaving.

Bad faith and avoiding responsibility for your life

There’s a particular form of self-deception that I used to practice all the time. I had this thing I wanted. To pursue it required certain sacrifices, certain consequences. No one likes consequences, myself included! But what I would tell myself was not, I don’t want to do this, because I’m unwilling to pay the cost. Instead, I would say: I can’t do this.

Saying that you can’t do something means that something is impossible for you to do—and that you can’t be held responsible for it. And sometimes that’s true. But it’s very easy to say that you can’t do something, when the truly accurate verb is that you won’t do it. You don’t want to. You’ve made a choice.

I used to tell myself, for example, that I couldn’t make time to write in my life. I can’t speak for anyone else, especially those who have more caretaking responsibilities—but the truth was that I had the time; I was just choosing to waste it on other things. I told myself that writing was more important to me than spending money on clothes—but then I would spend hours scrolling through online shops, instead of hours working on a Substack post or book review.

In May of last year, when I became aware of this hypocrisy—this gap between my intentions and my actions—I wrote in my notebook: “Deceiving oneself is existentially worse than disappointing others…I am moved by people who take charge of their own existence.” I was trying to confront myself, to notice where I was failing to meet my ideals.

“I am distressed,” I wrote in the next paragraph, “by people suffering under self-inflicted limitations, delusions; by people continually knocked back and beaten down by their own self-sabotage.” I felt myself to be one of those people, and I wanted to value my time differently. No more excuses! No more falsely saying I can’t write.

I had realized, essentially, that I was acting in bad faith. In Jean-Paul Sartre’s definition of bad faith, we have a great deal of freedom of choice in our lives—but we often deny this freedom, and the responsibility that comes with it. We say we can’t do something, when what we really mean is that we don’t want the consequences. As Oliver Burkeman writes in Meditations for Mortals (which I read and briefly reviewed in October):

Freedom isn’t a matter of somehow wriggling free of the costs of your choice—that’s never an option – but of realizing…that nothing stops you doing anything at all, so long as you’re willing to pay those costs…

…If we’re being honest with ourselves, the temptation is often to exaggerate potential consequences, so as to spare ourselves the burden of making a bold choice. (It’s a particular peril among the progressive-minded, I’ve noticed, to take the fact that a given choice might be unfeasible for the underprivileged as a reason not to make it yourself. But unless it’s you who’s underprivileged, that’s an alibi, not an argument.) It was a central insight of the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre that there’s a secret comfort in telling yourself you’ve got no options, because it’s easier to wallow in the ‘bad faith’ of believing yourself trapped than to face the dizzying responsibilities of your freedom.

Once we stop acting in bad faith, we can better recognize our agency—making choices that involve certain sacrifices, yes, but also offer certain rewards. One of those rewards is the self-respect only available to those who, as Joan Didion wrote, “have the courage of their mistakes.” People with self-respect

know the price of things. If they choose to commit adultery, they do not then go running, in an access of bad conscience, to receive absolution from the wronged parties; nor do they complain unduly of the unfairness, the undeserved embarrassment, of being named corespondent. If they choose to forgo their work—say it is screenwriting—in favor of sitting around the Algonquin bar, they do not then wonder bitterly why the Hacketts, and not they, did Anne Frank.

I used to be jealous of the people who seemed to just write more, do more, make more work than me! But lately I’ve realized that, while some are lucky to have an easier life (the prototypical trust fund kids, for example)…many of those people, in Didion’s words, knew the price of things. They wanted to make certain projects happen, and embraced the consequences.

How the world works, and how we want it to work

There was an election last week in America. Maybe you’ve heard about the results. Not just the results, but the distress about the results, the discussions about what went right in Trump/Vance’s campaign, what went wrong in Harris/Walz’s campaign.

Everyone has a take. Including me. But I find myself caught between two opposing stances. There’s the desire for certainty, for clarity, for expertise. I want to know how this happened—and perhaps I want to flatter myself by believing that I have a more comprehensive, clear-eyed view of the world than others. And then there’s desire to understand—to really, deeply comprehend and internalize—which requires a tormenting level of humility, the capacity to say: I don’t know enough about the world to understand this.

I had certain beliefs, for example, about the Democratic party’s failure to emphasize economically populist policies. These preexisting beliefs meant that I had already begun to think: Well, the Democrats lost because they did this and not that…

But what to make of charts like this, from John Burn-Murdoch at the FT, showing that—for the first time since 1905—all incumbent parties around the world lost voter share in elections this year?

When I saw this chart on Thursday morning, I realized I hadn’t thought about the macroeconomic forces enough—the pressures of inflation and migration that are affecting many democratic countries and their elections, not just the United States. Which isn’t to say that all my previous theories about the election have to be rejected—but maybe, perhaps, my self-satisfied understanding of the election needs to be shaken up a little.

It’s terrifyingly easy, as Nabeel S. Qureshi observed, “to think that you understand something, when you actually don’t.” In his Substack essay “How to Understand Things,” Qureshi writes that true understanding requires a great deal of intrinsic motivation:

You have to be able to motivate yourself to spend large quantities of energy on a problem…[because] not understanding something — or having a bug in your thinking — bothers you a lot. You have the drive, the will to know.

Related to this is honesty, or integrity: a sort of compulsive unwillingness, or inability, to lie to yourself. Feynman said that the first rule of science is that you do not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool. It is uniquely easy to lie to yourself because there is no external force keeping you honest; only you can run the constant loop of asking “do I really understand this?”

I believe that we often know—in some obscure corner of our minds—when we don’t really understand or believe something. But we can refuse to become aware of that, and thereby refuse the responsibility of doing better, intellectually and epistemically.

I’ve been thinking about how to understand the world better, politically and pragmatically. On Thursday morning, my friend Nick recommended the book Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government, by the political scientists Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels, who specialize in democratic theory, electoral politics and political representation. The book is a critique of what Achen and Bartels describe as the “folk theory of democracy”:

In the conventional view, democracy begins with the voters. Ordinary people have preferences about what their government should do. They choose leaders who will do those things, or they enact their preferences directly in referendums. In either case, what the majority wants becomes government policy…[This] constitutes a kind of “folk theory” of democracy, a set of accessible, appealing ideas assuring people that they live under an ethically defensible form of government that has their interests at heart.

The problem, Achen and Bartels argue, is that this theory is empirically false. Modern social-scientific research, they argue, shows instead that voters often exhibit “thin, disorganized, and ideologically incoherent” political preferences. They are often unable—given the demands of daily life; the disorienting clamor of media, especially social media; and the complexity of the ballot measures and policy platforms presented to them—to make informed, well-researched decisions at the polls. And political parties are not necessarily responsive to their voters. “The populist ideal of electoral democracy,” they write, “for all its elegance and attractiveness, is largely irrelevant in practice, leaving elected officials mostly free to pursue their own notions of the public good or to respond to party and interest group pressures.”

Chapter 6 of the book seems particularly relevant to the recent US election. Achen and Bartels use economic and election data from 1947 to 2013 to examine how a voter’s personal economic experiences affects their opinion of incumbent parties. There is a “strong tendency,” they note, for “voters to reward incumbents for good economic times and punish them for bad times.” But how voters do so is highly selective; the first 2 years of the previous president’s term are largely discarded, and voters tend to assess an incumbent leader’s economic performance based on the 6 months leading up to the election.4 Their votes are often interpreted as an assessment of whether they believe in the incumbent’s competence, and how much faith they have in a challenger’s ability to do better. But voters are not especially capable of judging this!5

Reading this has not entirely changed my prior beliefs. (I do still think the Democratic party could do better in articulating an agenda that resonates with the working class.) But it is helpful to have my interpretations challenged, and to consider how the “folk theory of democracy” is distorting my understanding of this election.

Historical analysis can also challenge our preexisting beliefs—sometimes, at least. Writing in The Point, just before the US election, the historian Scott Spillman observed that a great deal of popular historical writing in the US attempts to explain Trump in ways that are thin and unsatisfying. “Historians today,” Spillman writes,

are more apt to take sides with their historical heroes lest they give any comfort to their present-day enemies. Often in their books you see a neat division of the past into two teams, such that history becomes little more than a spectator sport…

[The assumption is that] If only everyone knew the correct story of American history—namely, the story told in these books—then they would all see the light and be proper liberals. The books often lack any acknowledgment that people of good faith might hold conflicting ideas about the story of American history or that, even if they agree about the basic story, they might draw starkly different lessons from it.

Historians can overreach, Spillman argues, by “pretending that their expertise affords them special insight into contemporary electoral politics.” This is a form of self-deception (on the historian’s part) that can contribute to an intellectually impoverished “Trump-fascism debate that has deadened certain corners of our historical and political discourse for the past eight years.”

The most honest historical writing, perhaps, is the writing that avoids easy, moralizing answers and instead challenges its readers. Spillman highlights the historian Matthew Karp’s writing as a positive example:

Karp has actually put in the work. His chief concern has been what is known as “class dealignment,” with upper-class voters now breaking more Democratic while lower-class voters trend Republican. Karp has prodded his readers to honestly grapple with this phenomenon precisely because it poses such a deep challenge to his preferred form of class-based politics, at least insofar as that project might be pursued through the current Democratic Party. Refreshingly, he does not regard the mass of American workers as former or future fascists, but instead as voters who, just like the rest of us, can be won over with better politics and policies.

Another historian that, to me, forces readers to think—to try to understand things more deeply—is Gabriel Winant, whose Dissent essay “Exit Right” has been widely shared in left-leaning circles online. Winant’s essay is a rigorous and unyielding critique of where liberalism has failed against Trump. “Just as in 2016,” he writes, “Harris supporters have fallen back on the racism and sexism of American society as an explanation for defeat. No doubt these are hulking obstacles, but they don’t suffice as omnibus explanation.”

Winant’s essay is worth reading for its thorough critique of the Democratic party, and his argument for a path forward. But there are a few particular arguments I’d like to highlight. Towards the end of the essay, Winant argues that

There are entrenched institutional liberal forces…that intone the threat Trumpism poses to democracy and the rule of law, yet work every day to defeat their own internal left-wing challengers: student protests, labor struggles, “woke excesses”.6

Winant argues that the Democrats erred in suppressing popular left-wing causes. But how he argues this is particularly relevant to the question of self-deception:

The phenomenon that Trump represents can only be defeated when liberal institutionalists cease trying to quash the insurgent left in the name of protecting democracy, and instead look to it as an ally and a source of strength. This is not because the ideas of the left already represent a suppressed silent majority—a fantastical, self-flattering delusion—but because it is only the left that has a coherent vision to offer against the ideas of the right.

There is this belief—which I’ve held in the past, too—that there are certain ideas that are just obviously good. That the ideas you agree with must be the ones the rest of the electorate hold, deep in their hearts.

What interests me is Winant’s assertion that certain ideas—socialist ones, say—are not necessarily uncontroversially popular. Political actors who believe in their ideas need to create that popularity, deliberately. As a friend of mine (who originally shared the Winant essay with me) observed, “A lot of people across the political spectrum seem to not understand this point, but it's what separates effective political actors and ineffective ones.”

Effectiveness—in politics, and in life—relies, I think, on our ability to meet reality. I wrote this to remind myself of the cost of self-deception, and to commit to the kind of rigorous, unyielding honesty that makes one’s life and work better.

Four recent favorites

Persimmons for autumn ✦✧ Riso prints for winter ✦✧ On loneliness, real or imagined ✦✧ The solution to seasonal depression

Persimmons for autumn ✦

My favorite autumn/winter fruit is the persimmon, and I loved the cheerful delicacy of this painting by John Zabawa—with the slightly wavering brown lines to convey creased fabric:

Riso prints for winter ✦

As we’re easing into winter—the season for cozy, comforting soups and (for many people) Christmas gifts—I also really liked these riso prints by Erin Jang, featuring “winter citrus like pomelo and clementines…and scallion, ginger, garlic, and enoki mushrooms—aromatics for homemade soups and jjigaes.”

You can buy a print here, and proceeds go to Heart of Dinner, a nonprofit to address food insecurity among Asian elders, primarily in NYC’s Chinatown. (Fun fact: Heart of Dinner was cofounded by Yin Chang, who played Nelly Yuki in the original Gossip Girl!)

On loneliness, real or imagined ✦

I can’t remember how I came across Cody Delistraty’s 2016 essay on loneliness, published in Aeon, but I loved this anecdote about Thoreau’s imagined versus actual experience of loneliness:

Interestingly, much of the idealisation of loneliness in art and literature turns out to be a façade. Henry David Thoreau rhapsodised his alone time. ‘I find it wholesome to be alone the greater part of the time,’ he wrote in Walden: Or, Life in the Woods (1854). ‘Why should I feel lonely?… I am no more lonely than the loon in the pond that laughs so loud, or than Walden Pond itself.’ Lo! How romantic to be alone! he begs his reader to think. And yet, Walden Pond sat within a large park that was often swarmed with picnickers and swimmers, skaters and ice fishers. In his ‘isolation’, Thoreau corresponded frequently with Ralph Waldo Emerson; and he went home as often as once a week to dine with friends or eat the cookies his mother baked. Of course he wasn’t lonely: he was so seldom truly alone.

The solution to seasonal depression ✦

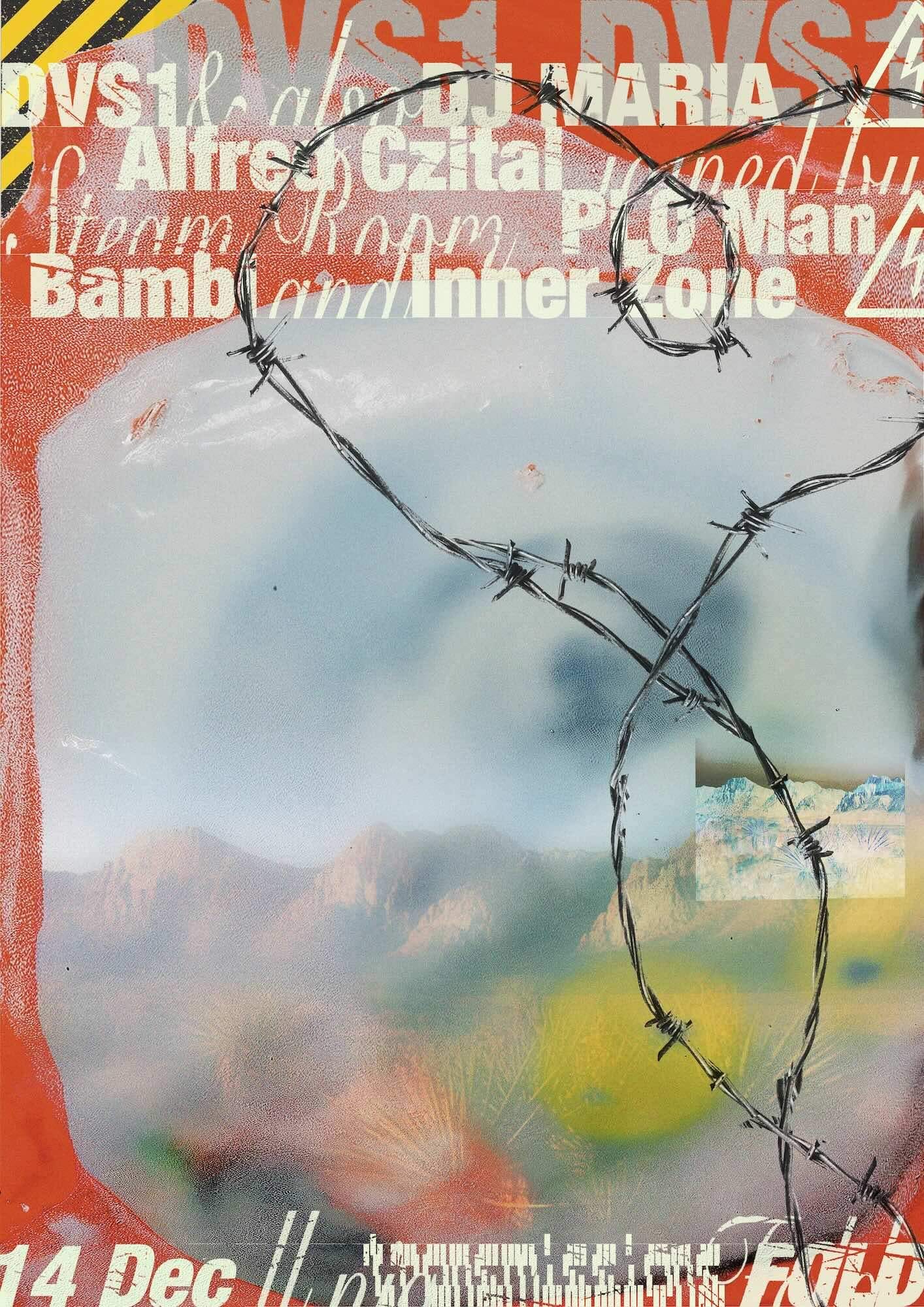

Forget cognitive behavioral therapy, SSRIs, yoga…according to one study, dancing is the most effective treatment for depression. I’ll also suggest, very anecdotally and unscientifically, that great graphic design helps too! I loved this event flyer, by the graphic designer and art director Alfie Allen, for a Transmissions club night in London.

The combination of a tall, thin script (with the lower half of the letters cropped—very elegant!) and thick, bold sans serif is so great. And the tension between the caution tape in the upper left and barbed wire (gritty, grimy, hard-edged) and the dreamy, soft-focus colors in the center…lovely.

Thank you all for reading my newsletter! I’m writing this from Temo’s Cafe in the Mission, with the late afternoon light streaming in and slanting across my screen. There’s a different quality to the sunlight in the autumn—it moves through air that is cool, sharp, invigorating; and the warmth it delivers feels more necessary, more welcome, than the stifling heat of the summer.

In a few weeks, I’ll be celebrating the one-year anniversary of this newsletter. I’ll write something brief about my experiences—not too annoying and growth-hack-y, I promise!—but if you have any questions for me about writing on Substack (or writing on the internet more generally), please comment below, DM me, or reply to this email! I’ll try to answer them in the next post!

And if you know anyone who might enjoy this newsletter—

In practice, of course, these forms of self-deception can’t be cleanly separated! To believe that you are a rare talent, that you deserve more (admiration, acclaim, remuneration) than others for your talent—that’s a claim about the self and of the other people in the world.

I’m quoting from Lydia Davis’s translation of Madame Bovary.

I’m quoting from the Pevear and Volokhonsky translation. For some reason, people online are always complaining about P&V’s translations, but I’m not sure why? I don’t read Russian, but as an English reader—I find their approach very charming! Here’s one of my favorite character descriptions from P&V’s Anna Karenina:

The prince enjoyed a health remarkable even among princes; by means of gymnastics and good care of his body, he had attained to such strength that, despite the intemperance with which he gave himself up to pleasure, he was as fresh as a big, green, waxy Dutch cucumber.

And the same sentence in Louise and Aylmer Maude’s translation:

The Prince enjoyed unusually good health even for a Prince, and by means of gymnastics and care of his body had developed his strength to such a degree that, in spite of the excess he indulged in when amusing himself, he looked as fresh as a big green shining cucumber.

I prefer the P&V, because the words The prince a health remarkable even among princes has such a lovely resonance to it. Also: he was as fresh as a big, green, waxy Dutch cucumber. (The commas between big, green, waxy—which aren’t present in Maude’s big green shining—create a sense of rhythm.)

The specific claim Achen and Bartels make is, that, based on their analysis:

It is possible to account for recent presidential election outcomes with a fair degree of precision solely on the basis of how long the incumbent party had been in power and how much real income growth voters experienced in the six months leading up to Election Day. Economic growth earlier in the president’s term seems to contribute little or nothing to the incumbent party’s electoral prospects.

The retrospective theory of political accountability is that voters use elections to assess “the performance of incumbent officials, rewarding success and punishing failure.” But when it comes to the economy, Achen and Bartels argue that

Our analysis provides no support for the notion that retrospective voters can reliably recognize and reward competent economic management…it appears that voters are no more supportive of incumbents who turn out, upon reelection, to preside over high rates of GDP growth…these results cast doubt on the notion that incumbents are reelected, even in part, on the basis of economic competence.

The journalist Hamilton Nolan has also written about this regularly. In May of this year, he published an essay titled “The Left is Not Joe Biden’s Problem. Joe Biden Is,” which specifically discusses how centrist Democrats were attacking young pro-Palestine voters for being insufficiently supportive of Biden (which, they implied, meant being insufficiently supportive of democracy over fascism).

This is splendid. Reminds me of: "Failures either do not know what they want, or jib at the price." W.H. Auden

Great essay, thank you.

I vaguely sense some inner contradiction in the essay. It's hard for me to formulate it yet. I'll continue to think.

I'm a person driven a lot by a need of self-respect. Granted at times it means not getting respect from others, which can be pretty painful.

I am also driven by a constant desire to learn more, knowing how much I do not know.

Then mustn't I extend those qualities to others? They might just as well be driven by self-respect as they understand it, which might prevent them from, say, ABC, and lead them , to, say, XYZ.

PS it's hard for me to predict what shape my writing will take, and in what language it'll be. That was a question about writing. Maybe it's okay and I should leave well alone, just try to do the best each time. Or maybe it'd be better to try and focus?

Yes I do have, unfortunately, well-based-on-reality "I can't". Of course I try to lie to myself and others by attempting to live like it ain't so. Based-on-reality "I can't" is a very bitter pill to swallow.

Thank you again