everything i read in january 2024

books, essays, poems, images ✦

Happy January 31st to all who celebrate! The first month of the year is always an exciting, auspicious time: all the energetic ambitions of setting new year’s resolutions…and the fresh, open feeling of a new beginning.

With January coming to a close, I’m reflecting on what I read, experienced, encountered, and consumed this month:

56 books (with 2 more in progress)3 films

1 poetry reading (for Sarah Ghazal Ali’s Theophanies, which I’ll discuss more below!)

1 rave

16 almond milk lattes

6 perfume samples (all from d.grayi; I’m especially excited for Phở-Gere, with notes of bean sprouts, star anise, oud, and galangal)

12 glossy pillar candles by Hay (for a housewarming)

Below, a deep dive into some of the books, essays, poems, and images I encountered this month.

Books

The first book I finished this month was Bruce Tift, Already Free: Buddhism Meets Psychotherapy on the Path of Liberation, which I wrote about on my January 1st post: you are good enough as you are. I’ve been recommending this to everyone—the book has subtle, unexpected, and profound insights into self-aggression and self-compassion, how to escape codependent dynamics in romantic relationships, and many other pressing issues in our contemporary psychological landscape!

I then read Geeta Dayal’s Another Green World, which was partly research for a forthcoming book review—where I specifically focus on mathematical and technological processes for constructing literary works—and partly because I’ve been really interested in Brian Eno’s processes for musical production in particular! More discussion in my last post, oblique strategies for starting a new project.

Next up was Yasunari Kawabata’s The Rainbow, which I didn’t love—it’s a very strange work!—but was intensely compelling and mystical (also mentioned here) and Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art. Elkin’s book is an intimate investigation into writers and artists, largely from the 20th century onwards, whose works are grotesque, ugly, angry, unsettling—and how they’ve shaped our understanding of women’s art and literature, and feminist art and literature specifically. The premise of the book was deeply, deeply interesting to me, but the writing—well, it fell flat. The book is written in an exuberantly loose, associative, fragmentary style that contains all the right reference points (Virginia Woolf, Carolee Schneeman) and introduced me to a number of new and compelling artists. But the references are pulled together in a dissatisfying way. As Rachel Cooke noted, in her review for the Guardian:

Obviously, [Elkin] did a lot of reading and gallery-going…I think there are times when it’s profitable for a writer to freestyle a bit: to show their workings, all those sudden unnerving blots and semi-revelations. But in the case of Art Monsters, I’m afraid there is no getting away from the fact that the result is desperately contingent. However hyper-alert Elkin was as she wrote…the connections she makes are sometimes so loose as to be invisible.

It was still worth reading—but more for the citations and bibliography than the text itself.

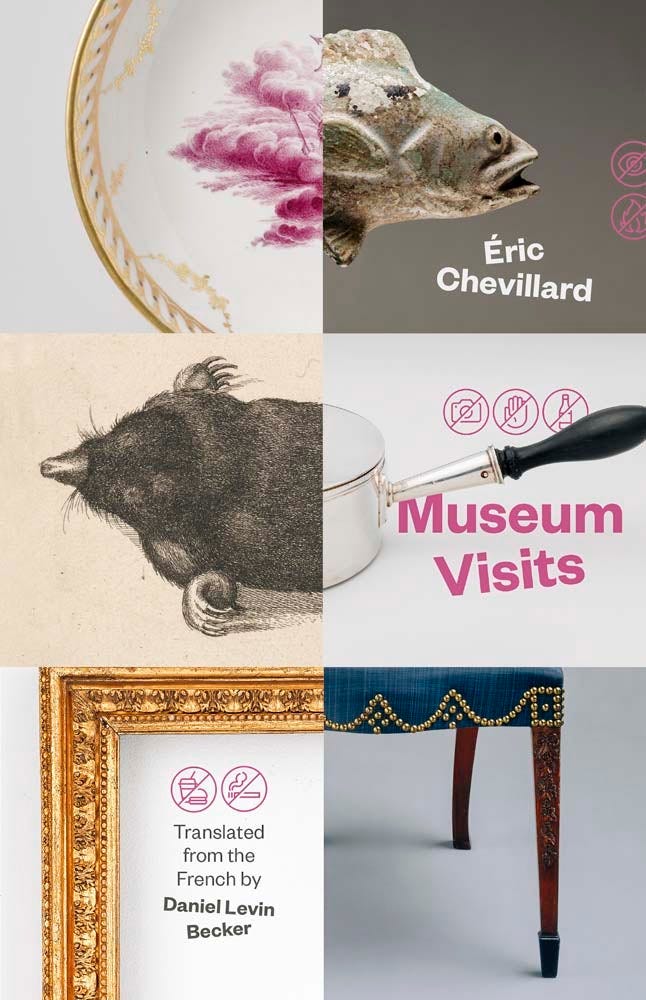

Right after that, though, I read Éric Chevillard’s Museum Visits, which was so incredible, with truly luminous and enticingly epigrammatic writing. I picked up a copy from the incomparable Green Apple Books in San Francisco, mostly because the cover was so good:

But the book itself is so, so, so amazing: 34 micro-essays, some just 2 pages long, that careen through a wide range of artistic and literary reference points to create playful speculative fiction–ish scenes, funny little character portraits, and reflections on writing. It’s translated beautifully by Daniel Levin Becker, the youngest member of the Parisian literary collective Oulipo.

The Oulipo movement also included Georges Perec and Italo Calvino, two of my all-time favorites. If you love their works, and particularly the lighthearted, playful tendency they have to take some small literary/mathematical/scientific idea and unfurl it into an essay or short story—then please, please read Chevillard’s Museum Visits. It’s so unbelievably good!

Here, for example, is how the first micro-essay, “The Guide”, begins:

So, right here is where Henri IV ran a hand through his beard, here's where a raindrop landed on Dante's forehead, this is where Buster Keaton bit into a pancake, here Rubens scratched his ear—let's keep moving, please, ladies and gentlemen—here is where the marquise de Sévigné coughed, here Arthur Rimbaud muddied his pants, here Christopher Columbus dropped his hat—stay together, please—here Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart became aware of the fact that magpies always travel in pairs, here Eugène Ionesco broke a shoelace, here Vincent van Gogh combed his hair with his fingers, here Charles Lindbergh grabbed his wife by the waist, here Marcel Proust—shh!—used a corner of his handkerchief to remove a bit of dust that was in his eye…

I am also obsessed with the second micro-essay, “Autofiction”, which seems to be about a young boy’s experiences with masturbation but is really about why we write, and why we read. Yes, really! You can read it here, thanks to Music & Literature.

(Edit: After I published this post, I realized I’d neglected to include Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger. Klein, an activist and writer who has spent decades focusing on anti-globalization movements, labor rights, climate justice, and anti-Zionism, opens the book by reflecting on a problem that has plagued her for much of her political life: that people confuse her with Naomi Wolf, a writer whose early feminist commitments—she wrote the now-iconic The Beauty Myth—have been seemingly replaced with anti-vaccination hysteria and a political alliance with Stephen Bannon, the former chairman of Breitbart News and Trump’s chief strategist.

From there, Klein goes on to investigate what draws people into conspiracy theories, especially in online communities, and how people with seemingly liberal or even leftist political affinities can be drawn into a more reactionary political posture. It’s a really great read—Klein doesn’t let leftists off easy; instead, she asks us to consider why so many people are drawn to right-wing and alt-right conspiracy theories, and how our own failures of political rhetoric may have contributed. Highly recommend; it’s very compelling and a great analysis of our political moment.)

So those are the 6 books I finished in January. I’m still reading:

Kyle Chayka’s Filterworld, about the distorting influences of algorithmic, often app-based recommendation systems on cultural production and consumption

Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s The Phenomenology of Perception, a dense but deeply moving philosophical text about how we perceive the world in subjective and embodied ways. I feel very lucky to be reading this with Zoe Tuck, a poet who, in her own words, “helps writers deepen their reading classes” through online classes—which feel, if anything, more like collaborations between Zoe, me, and the other writers and artists in the room. By the way—Zoe has some upcoming classes in March!

Essays

Nat Hartman reviews Anatomy of a Fall ✦✧ Miccaeli on perfume ✦✧ Andrea Long Chu and Merve Emre on criticism ✦✧ Andrea Long Chu on free speech and Palestine

Film criticism and Anatomy of a Fall ✦

For the Brooklyn Rail’s February issue—and published online just hours ago!—my friend Nat Hartman wrote a beautiful review of Justine Triet’s Anatomy of a Fall, which won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival last year.1

I really admire Nat’s writing, and how she moves from small and specific details—like her analysis of a scene where the fall of the husband is presaged by a scene of a rubber ball falling—to broader questions about the film’s narrative and style:

The world Triet constructs never feels romanticized or editorialized. Technology is not rendered sleek and unobtrusive but shown in all its bulk and inelegance. We see an iPad in a clunky case, propped against the piano. Mid-trial, the camera lingers on monitors that relay photos and transcripts of evidence to the attendees—they appear flimsy and clinical, clashing with the domed courtroom. Even the beauty of the snow-covered Alps, where most of the film takes place, seems incidental, the dramatic views sneaking in from the side. Instead, the whiteness of the landscape becomes piercing and threatening, a blank slate against which events are isolated and intensified.

As someone who’s relatively “new to film”, with a limited understanding of film history and contemporary trends, it’s a pleasure to read Nats’ review and see how she situates Anatomy of a Fall in the context of other genres (documentary, mystery) and films (by Ingmar Bergman, John Cassavetes).

My favorite perfume Substack on the internet’s most hyped perfume ✦

One of the first Substack articles I ever read was Miccaeli’s phenomenal in-depth analysis of Le Labo and its fragrances, published in 2021. She rarely publishes, but each post is—to use the parlance of our times—a banger.

Miccaeli’s latest post, “Sugar and Death: The Phenomenon of Baccarat Rouge 540”, is an incredible deep dive into a perfume that has, over the last few years, become the scent for millennial and Gen Z women. It’s a deceptively straightforward scent; the house behind it, Maison Francis Kurkdjian, describes it as simply having hedione, ambroxan, cedar, and saffron. I bought a sample of it in 2021 and loved the saffron note especially—I remember writing in my notebook that it smelled like what a high-end courtesan would wear to a dim sum restaurant.

Miccaeli’s essay goes into the ingredients, the history of the scent, how it became so popular online, and what its popularity says about fragrances and fragrance culture in an age of Tiktok perfume influencers.

My two favorite literary critics, in conversation ✦

This isn’t an essay, but an interview between two of my favorite literary critics: Andrea Long Chu, the 2023 Pulitzer Prize winner in criticism; and Merve Emre, a professor at Wesleyan and regular contributor to the New Yorker.2

In the interview, published in the New York Review of Books, Chu describes her career as a critic (beginning with long comments posted to her school newspaper’s website, and now as the book critic for New York Magazine); what it means to dislike something and write about it; Kant (I know nothing about Kant, so thank god Chu provides an extremely clear and accessile explanation), and more…

Emre and Chu are both incredible critics, and seeing how they articulate the role of literary criticism—sometimes they agree, sometimes they don’t—is fascinating:

MEI think you believe that people have a clearer sense of their own desires than I do. This is why I think it is fundamentally possible to persuade other people—because I think most people don’t actually know what their judgments are. Most people exist in a state of ambivalent, ineffable, inchoate, unknown desire. And perhaps the word that I would add to authority is something manipulation-adjacent, or persuasion-adjacent, or charisma-adjacent. You can persuade people that you know their desires better than they do.

ALCI agree that people don’t know what they want, don’t know what they think. That’s normal. For me, the goal is, I want you to read the piece and feel like you are having the thoughts of the piece in the moment. And that it is you. It doesn’t actually matter whether empirically you agree with it or not. For the period of time that you are reading this, you do, because you are having the thought. I’m giving it to you.

Andrea Long Chu on free speech and Palestine ✦

“Free speech”, in American politics, is one of those concepts that everyone seems to invoke incessantly and never define. This has become even more obvious as the ongoing genocide in Gaza continues, with vociferous debates about whether calling it a genocide is correct or not, how to appropriately condemn Israel’s actions—and, crucially, what form of retaliation is acceptable against those who consider it a genocide.

Because Andrea Long Chu is known for her aggressively principled critique, it almost feels strange to call her sensitive—but I think she is. In any aesthetic or political discussion, she seems to take the most interesting, subtle stance on a question. Reading her writing always opens up new ways of thinking, debating, and critiquing for me. And her essay “The Free-Speech Debate is a Trap”, published in New York Magazine in December, is a sublime example of this. She criticizes how discussions of Israel, Palestine, and Gaza get subsumed under bloodless, toothless discussions of free speech as a concept, and how we can leave this concept behind in the fight for justice:

[F]ree speech…asks us to have greater moral concern for the sanctity of ideas than for the lives of the Palestinian people…seeking “higher ground,” as the champions of free speech urge us to do, will only perpetuate the illusion that we are in yet another empty argument that can be safely contained by liberal norms; we will become so preoccupied with the integrity of the forest that we forget about the actual trees…

[F]reedom of speech without justice is like a planet without air. We do not protest the war on Gaza because we have an abstract right to do so; we protest it because it is one of the great moral atrocities of our lifetimes and because the widespread refusal to admit this in America is an atrocity in its own right. We are not just speaking; we are fighting with words. And we are fighting to win.

Poetry

Sarah Ghazal Ali (2024) ✦✧ Alice Gribbin (2023) Monica Youn (2019) ✦✧ Mei-mei Berssenbreuge (1984)

Sarah Ghazal Ali’s new book ✦

On January 19, I went to a reading and book launch for the poet Sarah Ghazal Ali’s Theophanies. The poems are lovely, formally exciting to hear and read on the page, and touch on motherhood, matrilineal heritage, loss, and faith.

One of my favorite poems—tender and difficult— is “When Nabra Hassanen Wakes Up in Jannah”, in honor of a young Muslim teenager who was killed during Ramadan in 2017. Four lines that stay with me:

Nabra Hassanen will walk

and reach for fruit, remembering

her mother, all those years

knifing berries into ordinary bowls.

I also loved the beginning of “Epistle: Hajar”, which has a soft, clear, accessible quality to it:

Agate, alyssum, apricot—simple pleasures

I can still pronounce in this desert.Love’s only dominion, the clear

well-walked path to drinkable water…

A poem by Alice Gribbin in the NYRB ✦

I am in love with Alice Gribbin’s poem “Rough Slabs of Jade”, which you can read in the NYRB’s November 23, 2023 issue or on Gribbin’s Twitter—she’s extremely fun to follow.

The poem, which I’ve reread maybe ten times this month, has a refined, nearly classical quality to it. I love the opening lines, which balance reverence with an uncanny otherness:

God of a lack of abundance, wanting, bone strength, ready god,

among the lemon groves your presence

is disputed. Even after

they are picked, the fruits keep breathing.

I’m still thinking about the fruits keep breathing; it’s so particular, so unsettling and beautiful.

A poem by Monica Youn ✦

Another poem with a strange, classical quality to it: Monica Youn’s “Study of Two Figures (Pasiphaë/Sado)”, published in Poetry’s February 2019 issue.

Reading this, I inhabit the body of an attentive antiquarian, someone looking at—investigating—analyzing two artifacts that might be millennia old. As the poem develops, these two artifacts become a way for Youn to comment on race (its presence, its intentional absence) in discussions of art and literature. The two figures—one male, one female—become “containers”:

Both containers allow the tourist and artist to touch the hot button, the taboo.

The desire and the discomfort remain contained.

Both containers allow the tourist and the artist to walk away.

The male and female figures remain contained.

Neither container—the rice chest, the hollow cow—appears to have any necessary connection to race.

To mention race where it is not necessary to mention race is taboo.

I have not mentioned the race of the tourist or the artist.

The tourist and the artist are allowed to pass for white.

The tourist and the artist are not contained.

Three poems by Mei-mei Berssenbreuge ✦

Lastly, I loved these three poems by Mei-mei Berssenbreuge, from a 1984 issue of Conjunctions. I am struggling immensely with which lines to quote—but perhaps these, from the poem “Texas”:

I used the table as a reference and just did things from there

in register, to play a form of feeling out to the end, which is

an air of truth living persons and objects you use take on

when you set them together in a certain order, conferring privilege

on the individual, who will tend to dissolve if his visual presence

is maintained…

The poet and novelist Ben Lerner (one of my favorites) described her work as “poems that seek to make the process of perception perceptible.” He also has this beautiful description of Berssenbrugge’s particularly long lines:

The radical extension of Berssenbrugge’s line heightens the reader’s awareness of time and space by making the reader aware that time and space are running out: the far right margin is a precipice.

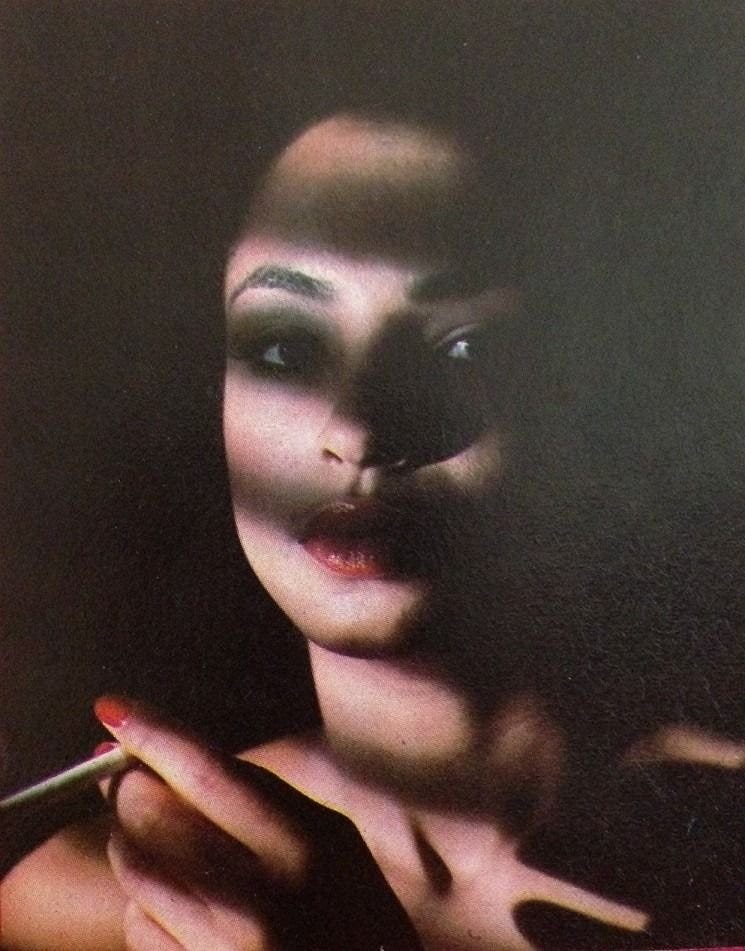

Images

These 2 images are, in Hito Steyerl’s terms, “poor images”—low-resolution, not even grainy (which is cool, sexy, filmic) but noisy (pixelated and laced with compression artifacts), But they’re beautiful to me, and maybe they’ll be beautiful to you too:

And that’s all for January. If you’re reading this from the northern hemisphere, I hope you’re warm and sheltered. If you’re in the southern hemisphere, lingering in the long days and sunlight—I’m jealous!

At Cannes, Justine Triet used her acceptance speech to sharply criticize the French government, especially the president Emmanuel Macron, for contributing to a “commercialisation of culture” that threatened French filmmaking, and for harshly repressing the “historic, extremely powerful, unanimous protest” over Macron’s pension reforms. Via CNN and The Guardian.

Emre has also been described as “one of the hottest—and most reviled names in literary criticism” in this fascinatingly gossipy Business Insider profile.

Immaculate taste! I’m gonna read these books too

Agreed on Doppelganger--the first thing I've read by Klein. I was impressed at how much mileage she got out of the central conceit and struck by the clarity, rigor and depth of her thought.