the occasional art report

the pros and cons of nostalgia, Wolfgang Tillmans, Korean ceramics, ideal translations, and the best show of Frieze London

In 2020, I borrowed a book from the library titled How to Write About Contemporary Art. I didn’t finish it, and I didn’t write about any art that year, but later on I began reading a book of the late, great art critic Peter Schjeldahl’s writing, and learned by example what I couldn’t learn from principle.1

Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light is an aloof title for an unusually personable book of art criticism. The 100 pieces inside, written from 1988 to 2018, include essays on—

Andy Warhol (“the artist laureate of capitalism”)

Pablo Picasso (“simple in the ways that counted…he was a line-drawing critter”)

Agnes Martin (“the most matter-of-fact of mystics”)

Florine Stettheimer (“securely esteemed—or adored, more like it”)

Peter Hujar ("who “lived the bohemian dream of becoming legendary rather than the bourgeois one of being rich”)

—and others, all described in Schjeldahl’s accessible, exuberant style. Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light, as Jarrett Earnest writes in the introduction, shows how “seeing is a contact sport.” In Schjeldahl’s writing, a stroll through an exhibition reads like a physical encounter of the most potent kind. He makes looking at paintings seem better than (almost) any psychedelic.

What did I learn from Schjeldahl? That art could be a first-person experience, not just an aloof, art-historical one. Prior knowledge—about an artist, medium and milieu—helped, but it wasn’t necessary. I felt less self-conscious after I read Schjeldahl, more open to establishing my own relationship to contemporary art. More open to writing about art, too, despite my lack of experience.

Today’s newsletter newsletter is about 5 contemporary art and craft exhibitions I saw in London this October. They include artists working with (and depicting) ‘90s technology; the first photographer to win the Turner Prize; a potter working with 15th-century Korean techniques; an artist who works with translated books; and more.

In this post — Nihaal Faizal’s The Magic Pencil ✦ Wolfgang Tillmans’s Build From Here at Maureen Paley ✦ Kwak Kyung-Tae’s solo show at Flow Gallery ✦ Miriam Stoney’s Ideal Translations at Tenderbooks, Oct 11–18 ✦ Clarissa, a group show curated by émergent and Soft Commodity, Oct 14–19

Nihaal Faizal’s The Magic Pencil

On the first Friday of the month, I stopped by the opening of the Bangalore-based artist Nihaal Faizal’s The Magic Pencil (Oct 3–Nov 1). The exhibition, curated by Olamiju Fajemisin and Ben Broome, is inspired by an Indian children’s TV show about a young boy, Sanju, whose magic pencil can bring anything he draws to life.

For the exhibition, Faizal took scenes from the TV show and recreated them on Megasketcher, a children’s magnetic drawing toy. They’re similar to Etch A Sketches (which I grew up with), with a slider on the right to erase everything. Though Faizal removed the eraser from these toys, there’s something appealingly uncanny about the implied transience of his drawings—especially in a gallery setting. I loved the depiction, too, of early 2000s objects like small point-and-shoot cameras:

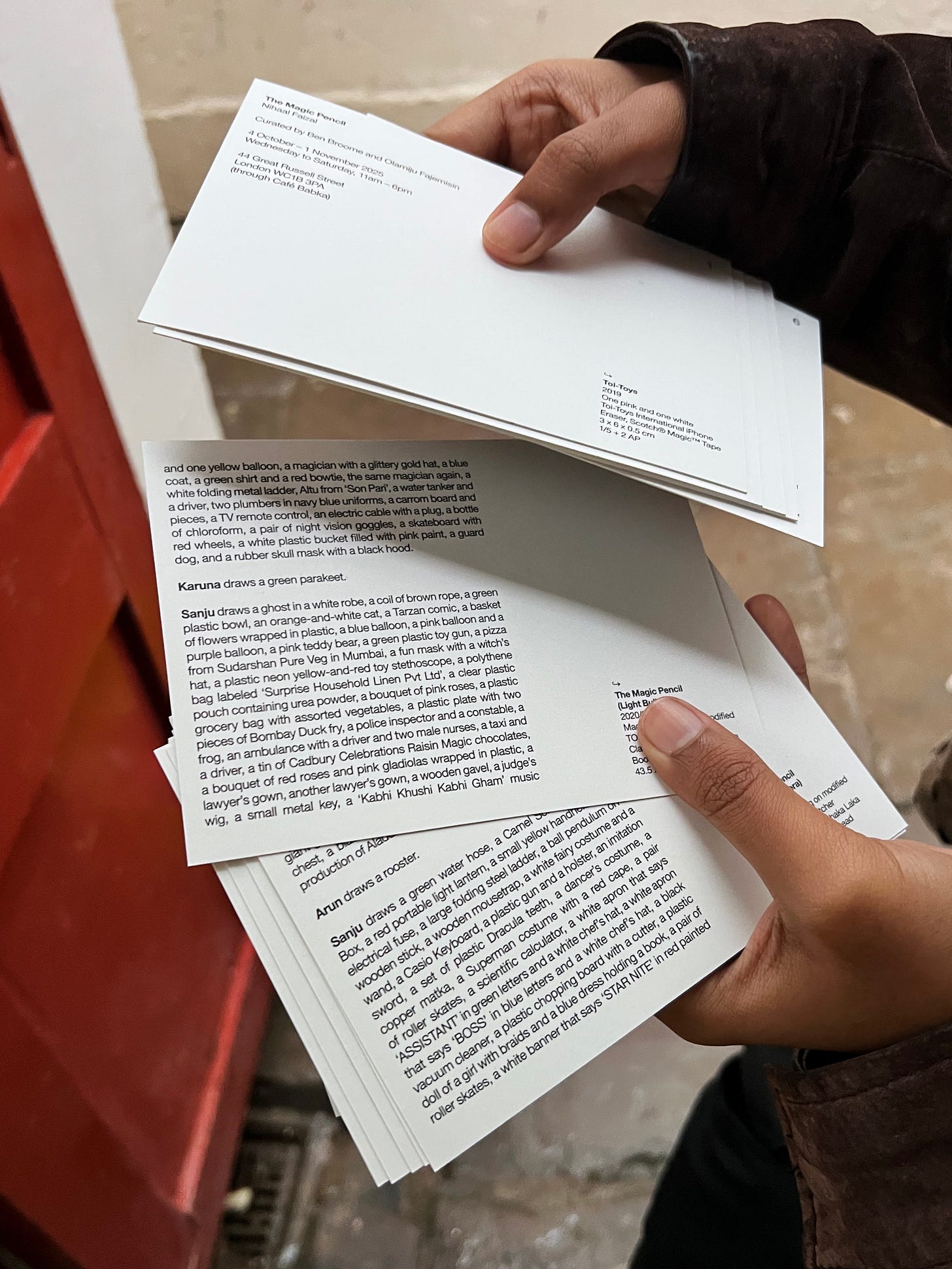

Faizal is also the founder of the artist publishing house Reliable Copy, which is stocked at Printed Matter in NYC and elsewhere. For The Magic Pencil, he also created a charming exhibition catalogue that lists every drawing that Sanju and other characters create during the 450 episodes of the TV show:

I love anything that takes the form of a list, and there’s something intriguing about having hundreds of TV episodes compressed into this form—you imagine what plot points might have led to Sanju drawing a police inspector and a constable, and later an ambulance with a driver and two male nurses, or a Casio Keyboard…along with more conventionally childish objects, like a pair of roller skates.

Faizal’s project is clearly nostalgic, but it’s a thorny, conflicted nostalgia. When I spoke to the artist, he said that revisiting the TV show was a disappointing experience. Though the objects Sanju draws disappear at the end of each episode, he still gets to create anything he wants—without incurring any consequences. It’s a jejune plot that holds up poorly in the present, when many adults (and adolescents, too) are conscious of the ecological consequences of our thirst for more.

Faizal’s ambiguous nostalgia interests me much more than a more linear longing for the past. The latter seems to be everywhere in contemporary art right now—and it’s not clear that it’s a good thing. In the latest Spike issue on nostalgia, the critic Jeppe Ugelvig observes that:

“The rule about Berlin,” writes novelist Elvia Wilk, “is that you always got there too late.” The same logic, it seems, applies to the city that is Contemporary Art. Upon arrival there, one is immediately told that the art used to be better, its people more authentic, its institutions less corrupted. Its denizens, Art People, will diagnose this decline by hinging it on characteristically flimsy evidence, usually the disappearance of a particular genre or a platform, or something along the lines of “commodification.” Bewildered, one proceeds to navigate whatever remains in the supposedly impoverished present. But not long after, one finds oneself lecturing some poor debutante about some particularly riveting edition of the Venice Biennale one visited ten years ago. Art People are notoriously nostalgic people, always certain that some golden age has just passed.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Build From Here at Maureen Paley

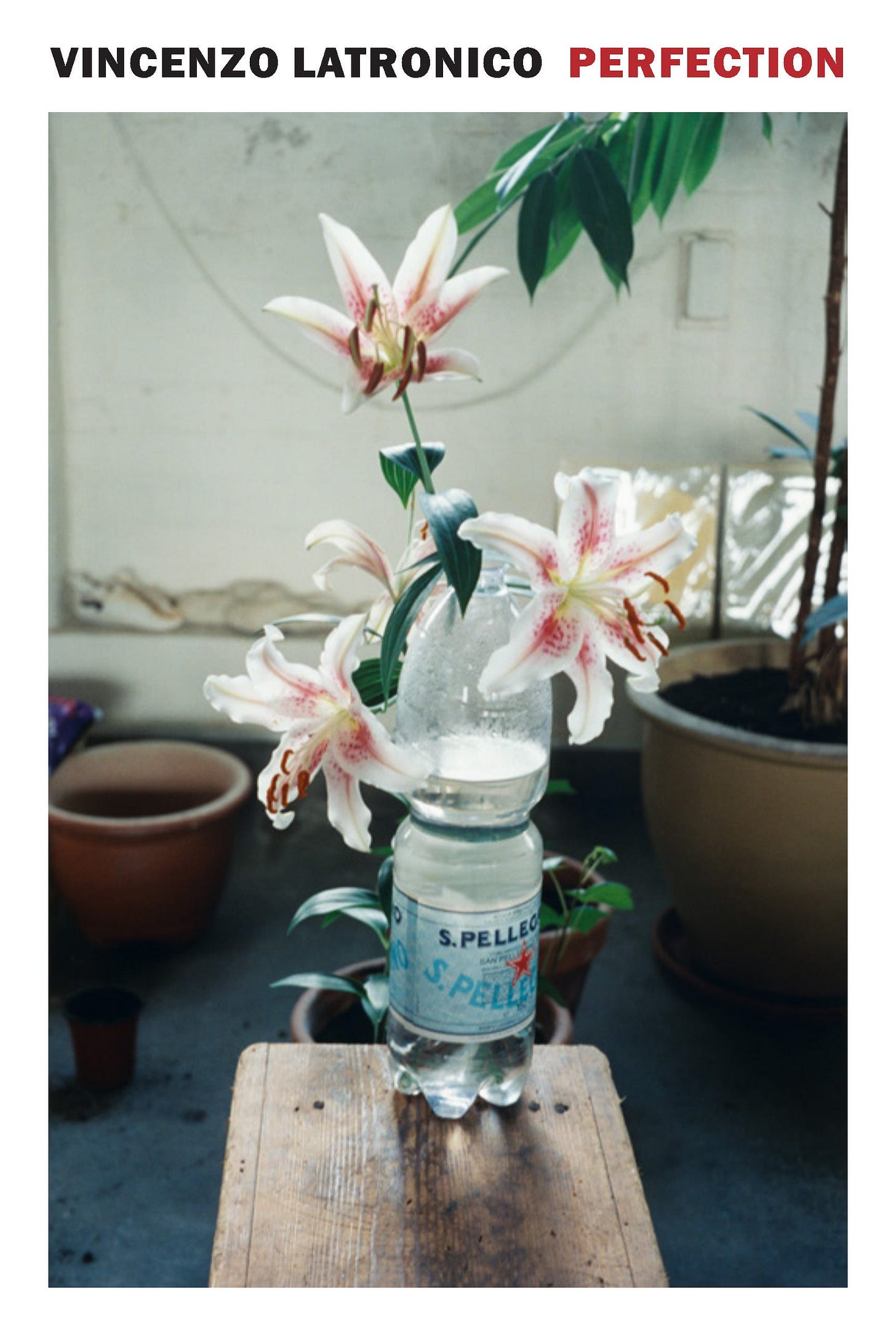

The first Wolfgang Tillmans photograph I remember seeing was of three stargazer lilies in a plastic San Pellegrino water bottle. By saw, I mean I scrolled past it on tumblr, where the improvisational feeling of the scene, and the gauzy, filmic quality of the light, impressed itself into my memory:

These informal still lifes are common in the German photographer’s work. They have an appealing directness: smooth stones arranged on denim. Half a watermelon and a lavender bedsheet, on concrete. Cherries and grapefruit resting on a crinkled, orchid-purple plastic bag. In a 2018 profile for the New Yorker, Emily Witt visited Tillmans’s studio:

It takes time to know if a picture is good, he said…and, even then, “I can’t know, I can only hope that they last. You can’t be too sure about something, because otherwise you’re too full of yourself or you can’t see if there is a weakness in the work.”

Tillmans walked over to a group of still-lifes…[and] stopped before one: an onion, sliced in half and placed on a piece of wood. “They pull in different directions: attraction, beauty, obviousness, not obviousness, how they sit in relation to the genre as a whole, and how they sit in relation to the genre within my work—within the genre of still-lifes, in this case,” he said. He described how the pattern in the onion related to the pattern of the plywood. “Is it striking in a good way, or is it too obvious, or too subtle? Sometimes it can’t be subtle enough, and sometimes the obvious is actually really good.”

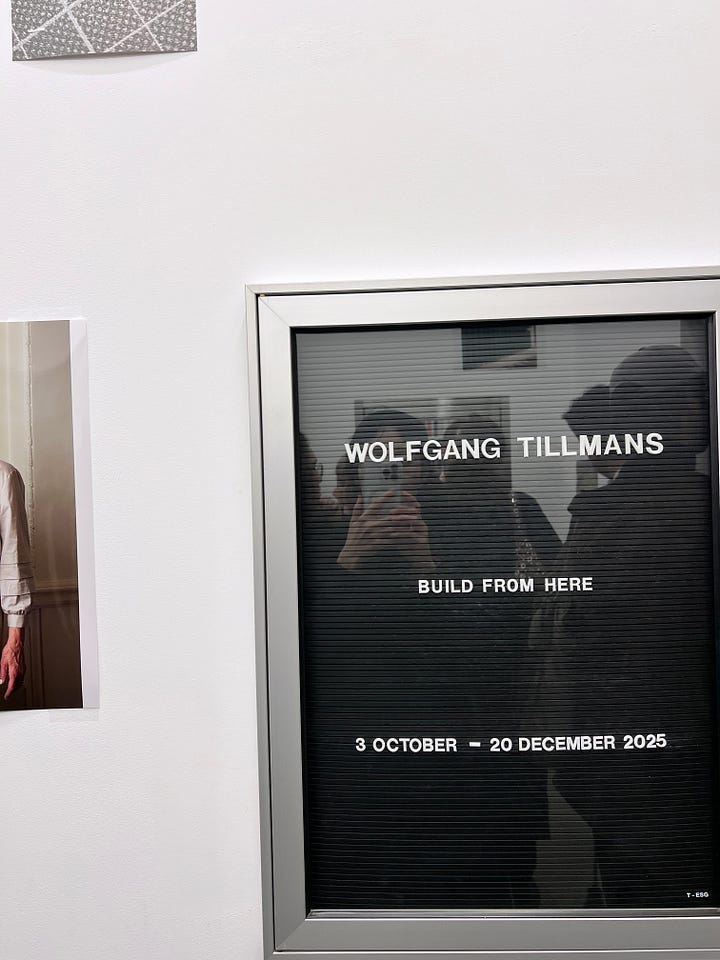

After seeing Faizal’s The Magic Pencil, my friend and I took the Central line over to east London, for the opening of Wolfgang Tillmans’s Build From Here (Oct 3–Dec 20).

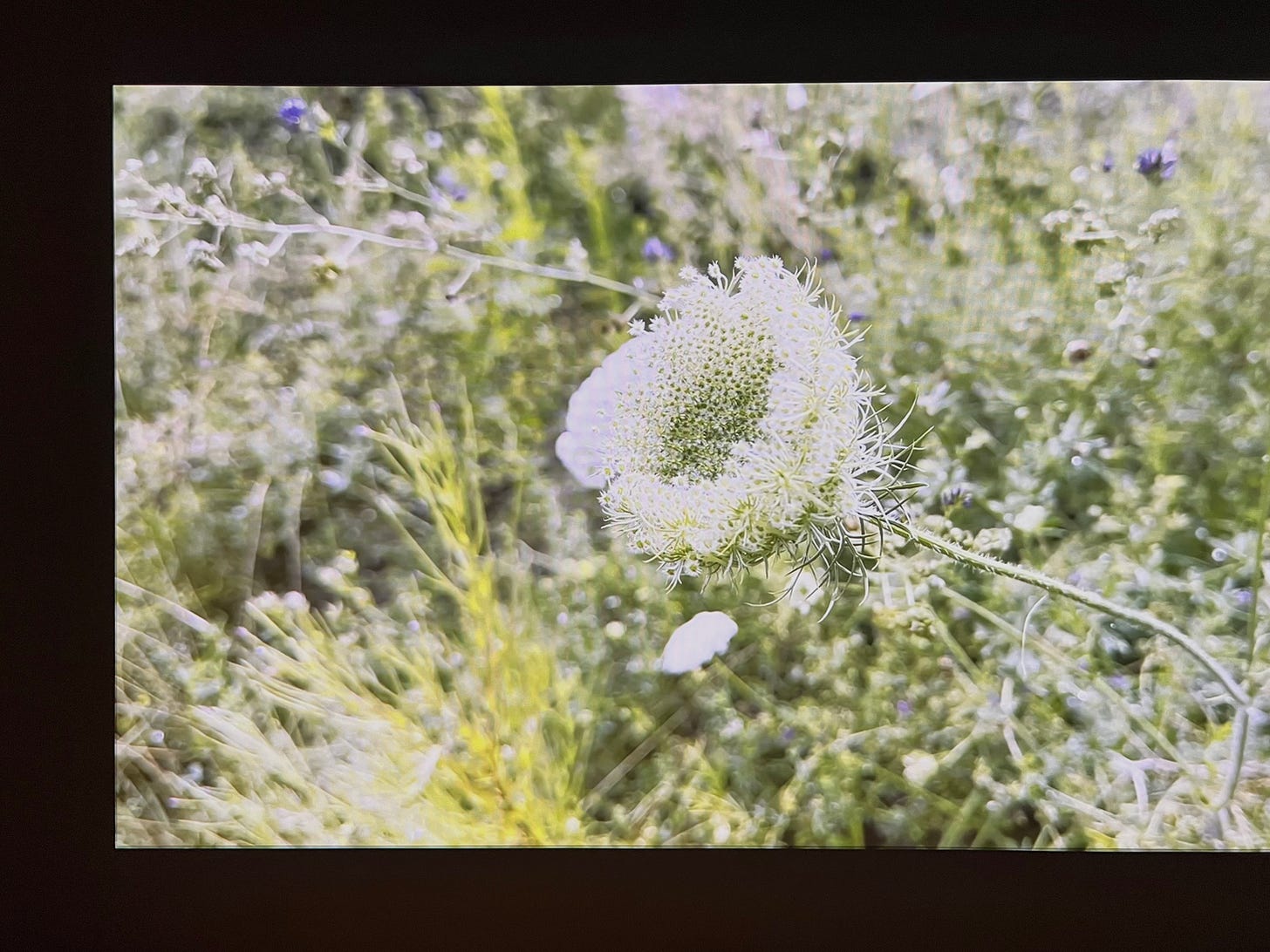

Build From Here is an exhibition of Tillman’s work across 3 spaces. We began with the smallest space, Studio M, near the restaurant Rochelle Canteen. Inside was a 4-minute video of a wild carrot flower gently bobbing in the wind, to the gentle, occasional notes of a kalimba.

It was already dark when we made the 22-minute walk east to Maureen Paley’s space on Three Colts Lane. The gallery itself was crammed with people, and I had to pick my way through each room, along the perimeter, trying to catch a glimpse of each photograph:

I spent a long time in the room devoted to Travelling Camera, a new video work by Tillmans of a camera sweeping over—in halting, shuddering movements—the smoothly machined back of a display monitor. Cables snaked across the surface, which was strewn with sand dollars and loose vintage stamps. I liked the collision of natural and machined artifacts, and the gestural sweep from earlier forms of information (physical mail) to newer forms (telecommunication).

The final space, and the largest, was across the street in Wolfgang Tillmans’s former London studio. There was an immense crush of people outside: queuing to enter, clamoring to get in the queue, diffidently observing the queue from a distance. There was a man at the door that seemed to be occupying the role of a bouncer, plucking certain people from the crowd and ushering them in, and politely holding everyone else back. It felt like a scene from The Last Days of Disco.

When the door had disgorged enough people, calm and unhurried on their way out of the gallery, we were finally beckoned inside.

There were photographs printed on letter-sized sheets of paper, or smaller, and simply taped to the walls. Some of the larger ones were hung with discreet white binder clips:

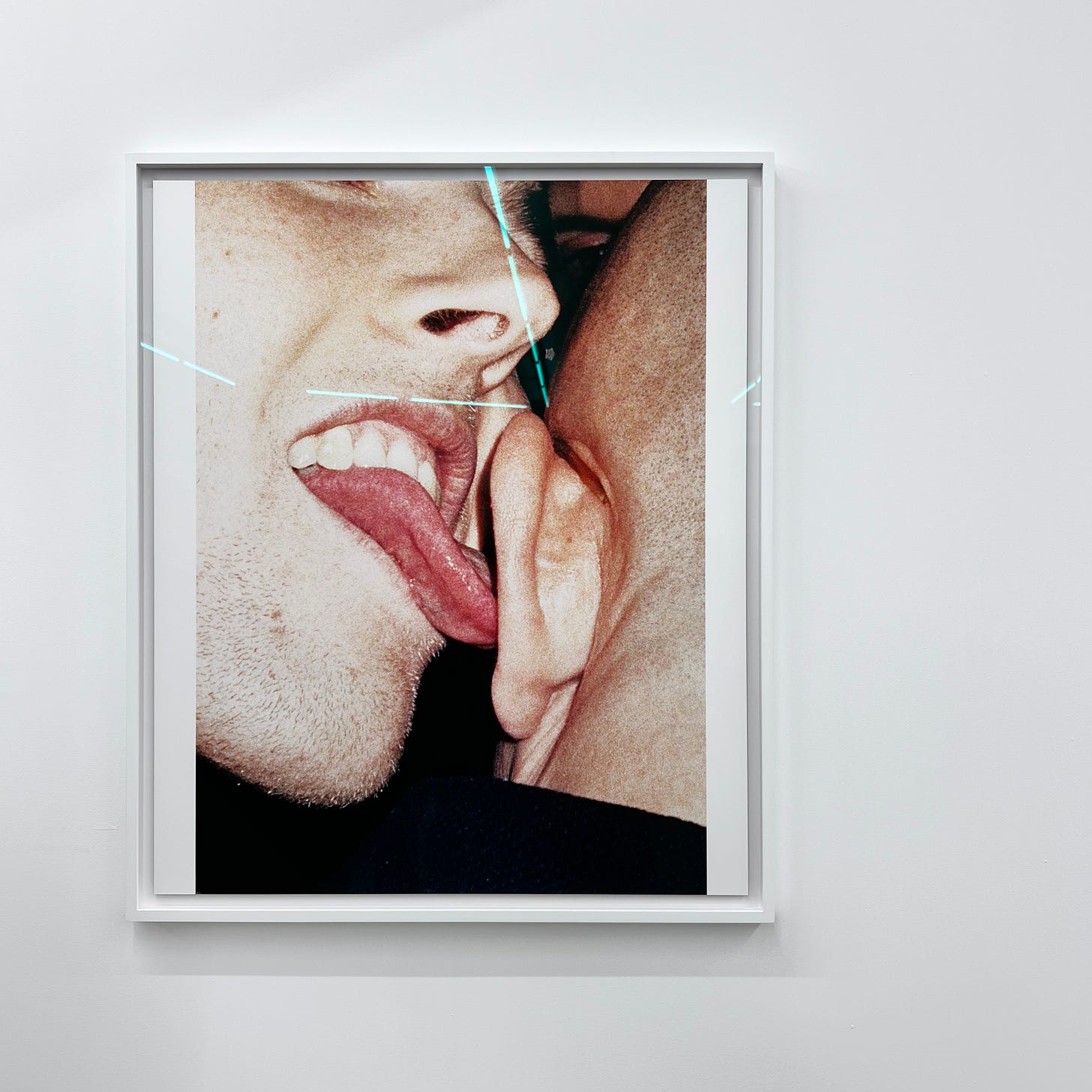

And others were more traditionally framed, like an image of man about to lick someone’s ear:

It’s a charismatic and playful photograph. On my way out of the gallery, I found myself back in front of the ear, smiling. “Play,” as Tillmans once explained to the journalist Arthur Lubow, “has always been of serious importance to me.”

In an economized and puritanical world that is putting a priority on reason, to do something nonsensical is a strong and life-affirming experience, which puts everything in perspective.

Kwak Kyung-tae’s solo show at Flow Gallery

In mid-October, I went to see the Korean potter Kwak Kyung-tae’s work with Jennifer Bin. I have the barest, most primitive understanding of how ceramics are made, but Jennifer—who’s been working with clay for years, and even made her own kiln!—gave me a brief history of Korean ceramics, and how prominent British potters like Bernard Leach were influenced by Japanese and Korean techniques.

I love being introduced to a craft by someone who understands it on a very deep, foundational level: the chemical composition of the clay and slip and glazes; the distinctive qualities of wood-fired ceramics; how small variations in the glaze revealed how objects were positioned in the kiln, and where the fire was burning, and how much oxygen was available inside.

In an interview with the gallery, Kwak elaborates on his approach to buncheong ceramics, a technique from the 15th century where pieces are coated in a white slip to create different designs:

Traditionally, buncheong is celebrated for its clean, white surface; an elegant “makeup” applied to clay, as it’s often described in Korean. But my approach to buncheong departs from that classical ideal. I don’t seek purity or perfection in whiteness; instead I treat the white slip as a blank canvas, a starting point for something more elemental.

When I paint on the surface, I am not only applying imagery. Rather, I am initiating a dialogue between clay, slip, and fire. In the reduction kiln, iron in the clay body interacts with the whiteness of the slip, creating soft blooms of pink, shadowy grays, and sometimes deep, unexpected hues. These iron blooms are unpredictable; formed not by control, but by surrendering to the alchemy of heat and time.

What first drew me to buncheong was this tension between refinement and rawness. Beneath the surface of tradition, I found space for spontaneity, contrast, and elemental transformation. The fire doesn’t just finish the work—it reveals it. My buncheong is not an act of covering, but one of uncovering; not a mask, but a mirror of process and material truth.

I was particularly drawn to a bowl where the white slip was applied in bold, contrasting streaks—with dark, iron-rich clay showing underneath, and flashes of copper here and there:

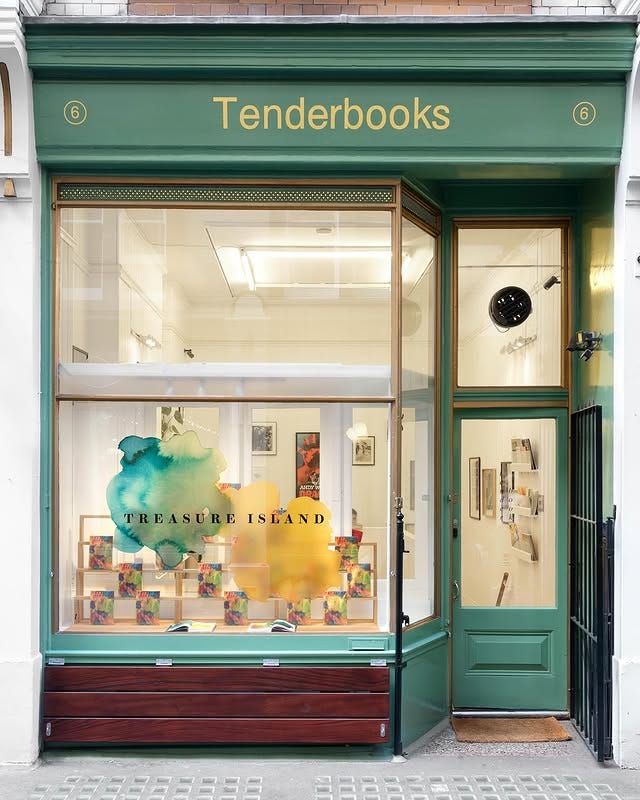

Miriam Stoney’s Ideal Translations at Tenderbooks

I find myself at Tenderbooks once or twice a month—it’s one of the best bookshops in London, especially if you’re interested in artist books. The tiny space (just 48 square meters!) is filled with beautiful zines, rare art books, novels and nonfiction from independent presses, and more. I love how idiosyncratic many of the books are—like Thomas Sauvin’s Till Death Do Us Part, which has photos of people smoking at Chinese weddings, stored inside a cigarette box. (Each restock sells out almost instantly.)

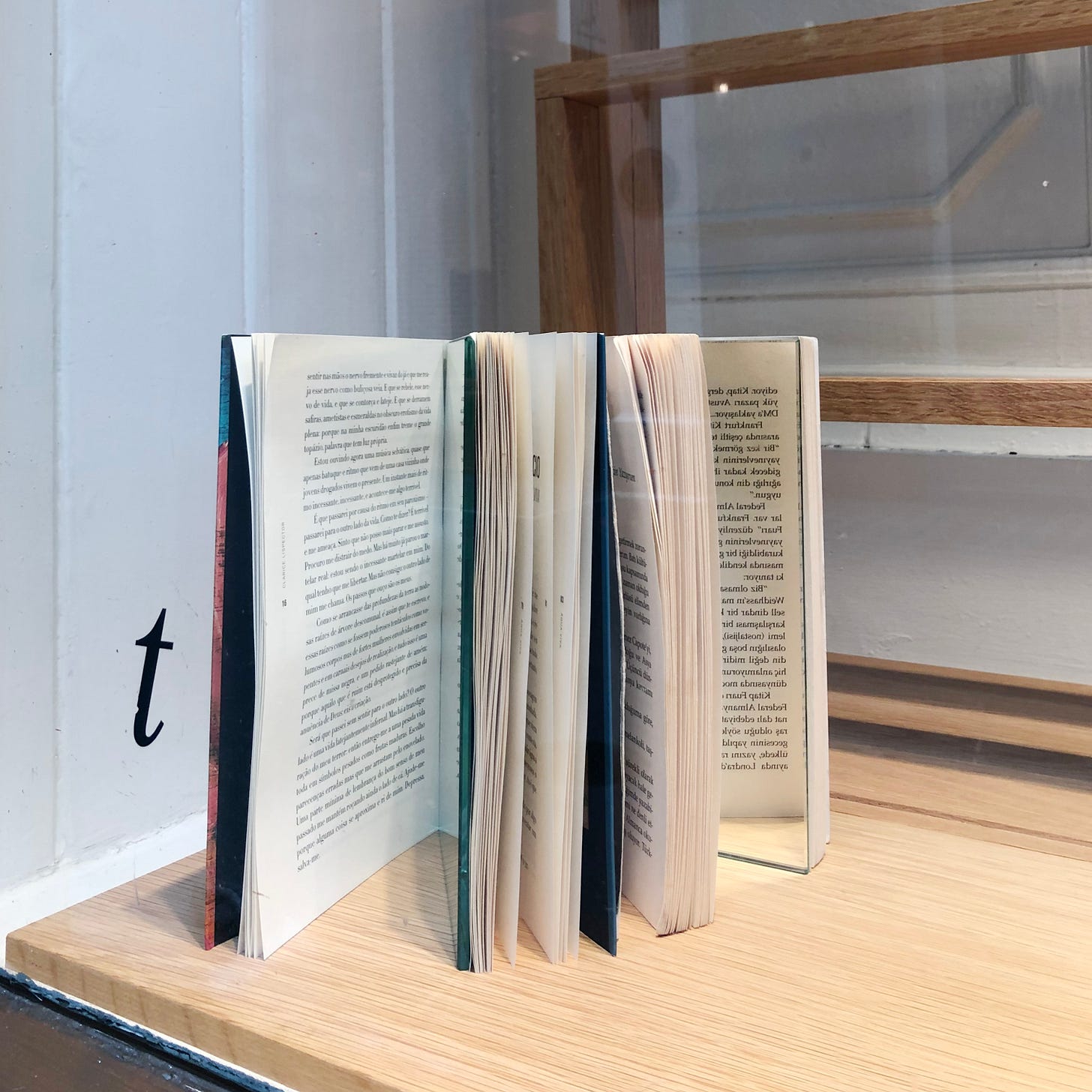

For Frieze London, the Tenderbooks window display had a site-specific installation by the artist, writer and translator Miriam Stoney. In Ideal Translations, non-English books are paired with with book-sized mirrored panels, reflecting the texts and evoking the process of translating language—and the shifts in meaning that inevitably occur.

I stopped by on Saturday, October 18 (for a “tender breakfast viewing”) and loved how elegant and succinct the installation was. It also made me want to see more of Stoney’s work. Stoney studied art history at Oxford, architectural history at the Bartlett School of architecture, and now lives in Vienna. In an interview last year, Stoney describes how she began to create visual artworks:

At Oxford, everyone was so genuinely, or maybe earnestly, interested in the pursuit of knowledge within the one specific field they’d signed themselves up for. But this pursuit of knowledge also led to a culture of hoarding. Hiding library books, refusing to share notes from lectures, and maintaining tight social circles according to which schools people went to…I started producing visual art and performances when I realized that there were so many gaps in the “knowledge” I was supposed to have gained through study. The point was not to fill these gaps with some supplementary, positivistic, though equally inadequate knowledge, but to consider, tease, and probe these gaps and their relation to other aims that interest me more than knowledge: flourishing, understanding, love, and joy, to name but a few.

Her interest in architecture and knowledge production comes through very naturally in the works she made for her solo show at Brunette Coleman last year:

I love works that are variations on a theme, iterations on some core structuring concept—like these L-shaped sculptures that reference furnishings and interior decorations:

Stoney speaks English, German, and French, and grew up around Punjabi speakers. Her work often incorporates different books, languages, and texts—like in Real objects, sensual qualities, which features tiny beds that different books are tucked into:

“Books,” Stoney said,

are especially interesting to me because they promise escapism, not only in the sense of getting lost in a story but also in terms of social mobility. This was the point of tension in Real objects, sensual qualities: the image of the book in bed is taken directly from the Sikh temple, the Gurdwara, where the holy book, the Guru Granth Sahib, is treated with the same reverence as any other guru and therefore given a bed. The difference with my sculptures is that the books don’t get woken up in the morning and brought to bed at night, as they do in the daily Sikh ritual. They exist as inert markers of another cultural tradition, other philosophical traditions, which happen to be the ones that gradually brought me further and further away from my Sikh heritage.

Stoney’s work is so ideally suited to my interests—architecture, writing, translation—and I’m looking forward to what she does next.

Clarissa, curated by Émergent and Soft Commodity

My plan, after seeing Stoney’s installation at Tenderbooks, was to go home and spend the day writing. But instead I stopped by Clarissa, after reading an article by Sofia Hallstrom that described it as “the hottest art show of Frieze Week.”

The show was co-curated by the artist-run magazine émergent and the London gallery Soft Commodity, and included works by 29 artists. As Hallstrom observes,

The juxtapositions here are intuitive rather than chronological; works are brought together through shared material sensibilities and formal composition…“There are artists in their twenties alongside Turner Prize nominees,” the editors note. “Not because of contrast, but because of a lineage of shared values and shared approaches to form. The relationships reveal themselves if you spend time with the works.”2

Clarissa was held at a former club and sex shop, and works were installed so that they interacted with the idiosyncracies of each room. I loved this sculpture–painting by Oscar Enberg, which was hung in a small alcove, and how the carefully assembled forms pair with the congregation of light switches and outlets on the wall:

In the next room, I was instinctively drawn to the London-based artist Hamish Pearce’s Tools, an elegant and inscrutable collage of two images printed on aluminum, and a silver object that looked like the top of a cranium, with a glistening raspberry hung inside:

On the opposite end of the room was a photograph by the New York-based artist Kayode Ojo. It’s a blunt-force depiction of wealth—which feels even more stately when bracketed by the room’s floor-to-ceiling columns—but the scene depicted is hard to read. Whose arm? And whose hair? Is it a night out? A night in?

I wasn’t familiar with Ojo before this show. After reading an Artnet article about his 2023 exhibition at David Zwirner in NYC, I’m now interested in seeing Ojo’s sculptures—which Taylor Dafoe describes as “intricate assemblages of stemware, jewels, and other expensive-looking wares.”

Most of the shiny objects that make up the artist’s sculptures are not genuine items of luxury, but budget imitations—rhinestones, not diamonds; acrylic, not crystal. Then again, that’s the rub: even if these things are cheaply made, they have, through the context of the gallery, been turned into art…

Even when the artist includes authentic pieces of high-end merchandise alongside their bargain-bin counterparts, he does so without distinction. Ojo isn’t interested in debasing his expensive objects any more than he is in reclaiming the cheaper ones as kitsch. “That’s not necessarily my focus,” he said when asked about the worth of some of the products in “EDEN.” “It’s something I’d prefer to leave as it appears.”

…Growing up in an evangelical Christian home in rural Tennessee, Ojo didn’t have access to fine clothes and precious stones, and he didn’t aspire to, either. The interest in commercial objects has always been about their formal properties first, their symbolic value second, he explained.

After Ojo’s photograph, I passed into another room with a disco ball hanging from the ceiling, and a silkscreen print of a round, artificially-lit ball with the word motivation stretched across it.

The motivation piece is by Michel Majerus, an artist I’ve been interested in ever since Lucas Gelfond sent me an interview in Spike about how the artist Cory Arcangel works with Majerus’s archive. Majerus is a Luxembourgish artist who passed away in 2002. Arcangel received permission from Majerus’s estate to work with Majerus’s laptop, and with the help of Dragan Espenschied—the preservation director of Rhizome, and an artist himself—booted up the laptop and began recording “let’s play” videos on YouTube of Majerus’s Photoshop files and other documents.

It felt very special to stumble across Majerus’s work at Clarissa—it felt obscurely significant to encounter this artist I’d been interested in and had been, subconsciously, seeking out. And Majerus’s work is just funny and charming and charismatic!

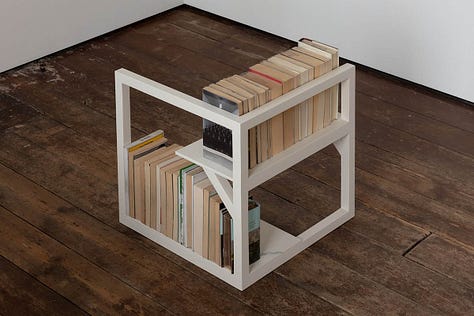

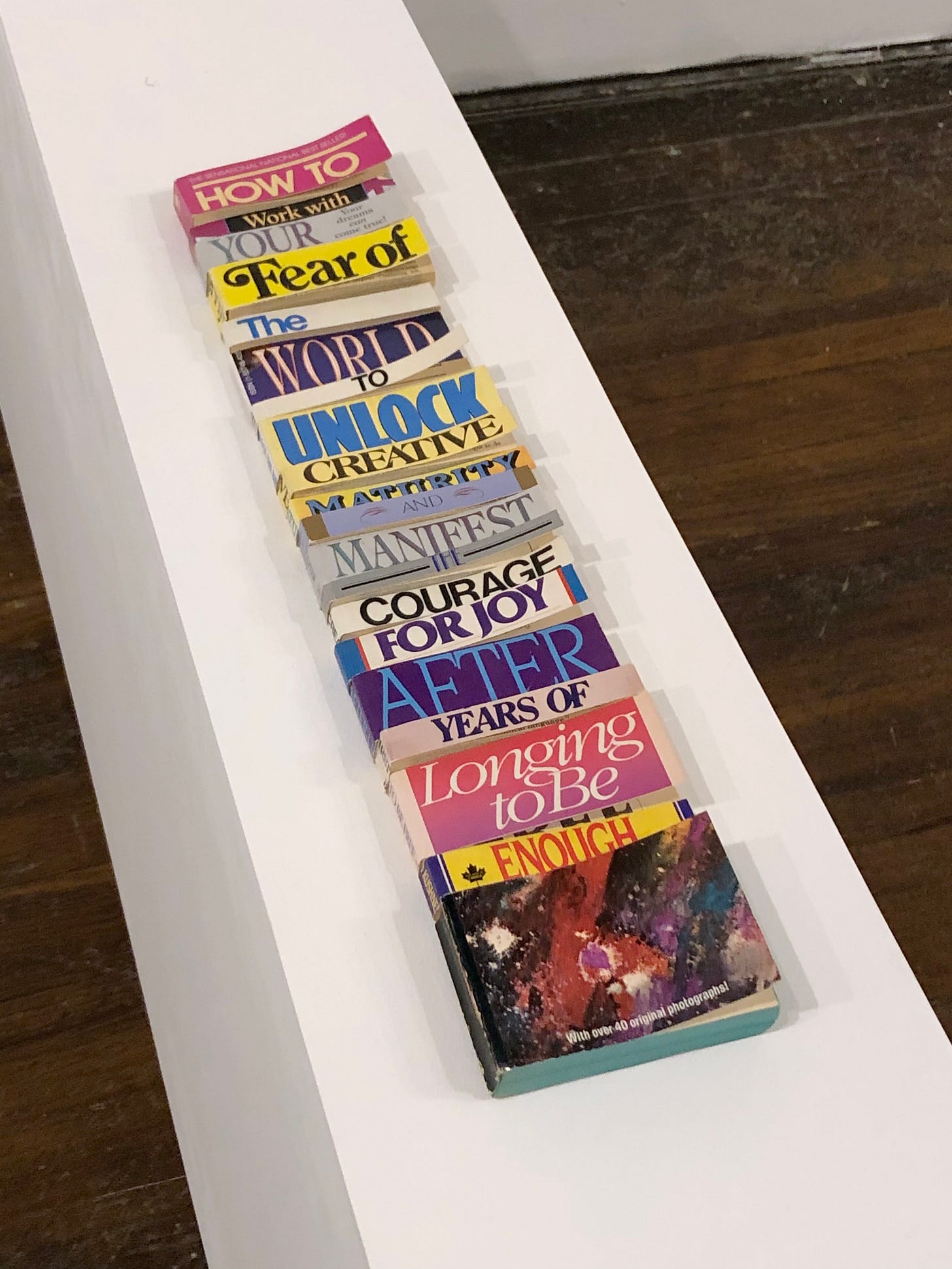

In the basement of the Clarissa show was another work I loved—as someone sadly addicted to self-help books:

By assembling slices of different self-help books into this stretched-out sculpture, Wiebe calls attention to the earnestly stentorian tone of self-help titles. It does, unfortunately, sound like a book I’d read. And if you, too, are shamefully obsessed with self-help books, it’s worth reading Erik Baker’s latest essay in The Drift:

Like most Americans, I’ve known the frustration and resentment that follow catechesis in the religion of self-fulfillment. I understand what it’s like to be told to look within yourself to find your destiny, your calling, your deepest desire, and to be assured that hard work and the right attitude can make it real: the excessive self-reverence, and then the inevitable self-recrimination. That there is now such a demand for books about the inevitability of failure and the wisdom of not giving a fuck suggests that many of us today suspect that our selfhood is a flimsy foundation on which to build a life, inadequate to the insuperable obstacles that prevent us from imposing our designs on the reality we inhabit. We’ve been tricked, or have tricked ourselves, into overestimating our own agency — and we hope a firm Stoic hand can smack us back into perspective.

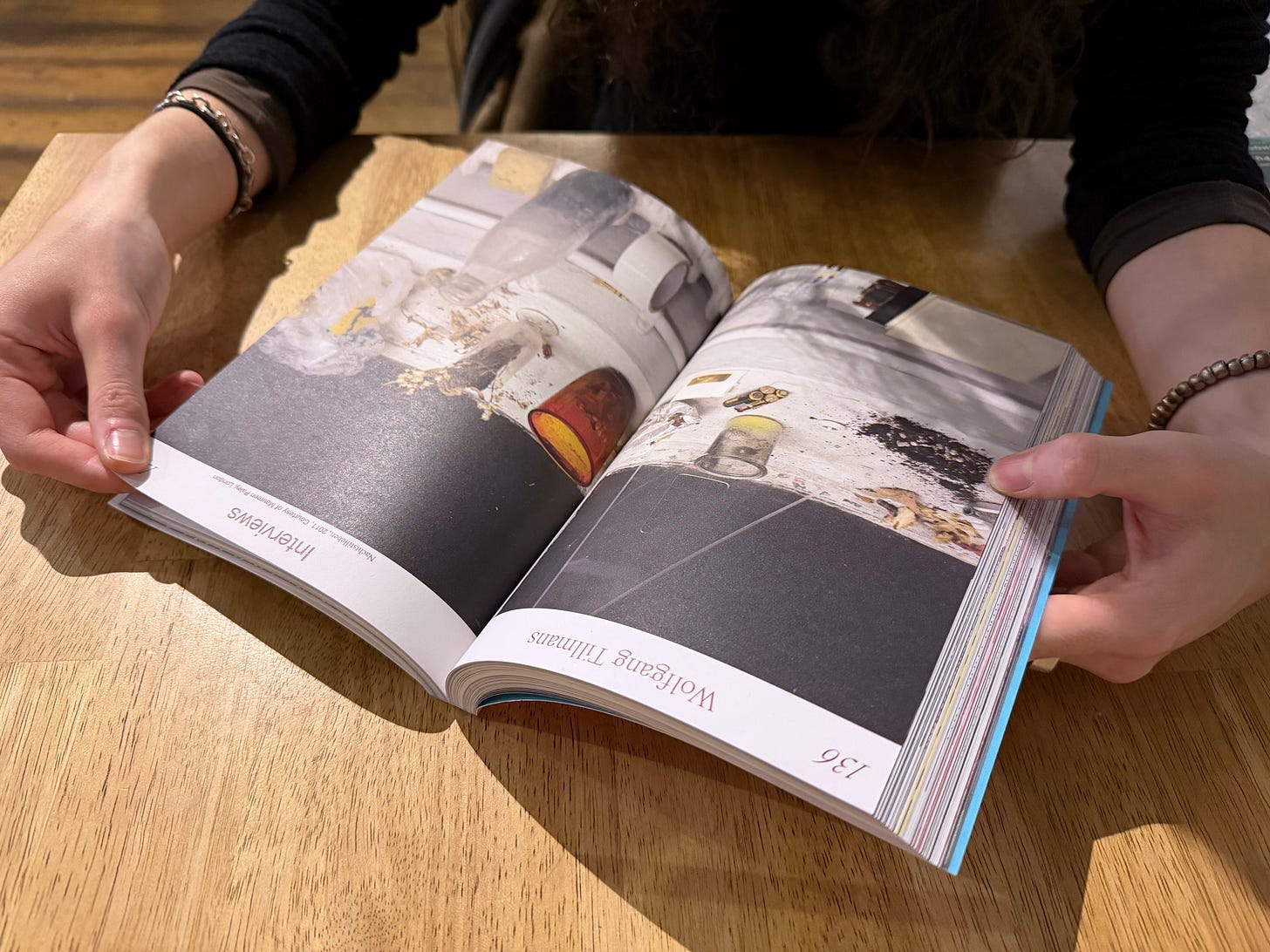

Before I left Clarissa’s space on Caledonian Road, I bought a copy of émergent’s latest issue, which includes profiles and interviews with Wolfgang Tillmans, Bernadette Corporation, Susan Cianciolo, and others. It’s worth buying: typographically daring, beautifully printed, and almost like holding an exhibition (or 12) in your hands.

And now it’s November, and I’m curled up at home writing this. I’ve spent the last few hours realizing just how hard it is to describe an artwork—a shape on a wall, a form in a room—and how exciting, too. I’m still figuring out how to write about art!

But I love reading critics like Jennifer Krasinski and Elvia Wilk and others write about art. If nothing else, the effort of writing pushes me to see, to observe, to go out into the world and immerse myself in the unexpected.

Three recent favorites

The half-meter tea ceremony ✦✧ “Merely a hobby” ✦✧ Colombian electro-pop

The half-meter tea ceremony ✦

Jennifer Bin on hiking, camping, and having tea in the Alps—including some lovely details about Tang dynasty poems and how they might have influenced contemporary tea-drinking trends:

The 半米茶席 (half meter tea ceremony)…is a recent trend in China focused around the core belief that tea ceremony is everywhere in life. This trend encourages people to engage in tea in all environments, especially in nature. In China, there is a popular movement on social media to return to nature, and the practise of drinking tea in nature is a way to reclaim this harmony with the natural world. I believe this is a continuation of practices common in ancient China, as recorded in Classical Chinese literature.

There are over 2000 poems in the Classical Chinese literature oeuvre about tea drinking, with over 200 composed in the Tang and Song dynasties alone. The poems typically describe the spirit of drinking tea. While tea permeated almost every aspect of Classical Chinese culture, the ancients often enjoyed drinking tea in different natural settings, with special emphasis on important spiritual locations such as Mount Tai (泰山, one of the 5 sacred mountains in Daoism) or Five-Platform Mountain (五台山, one of the 5 sacred mountains in Buddism).

“Merely a hobby” ✦

I loved Dizzy Zaba’s recent newsletter on refusing to choose between their job and their writing—a profoundly relatable feeling for me!

It’s not as simple as a choice between my job (organizer) or my hobby (writer). I reject (even resent!) categorizing my organizing as merely a job and my writing as merely a hobby, though organizing pays for my life, and writing doesn’t.

Colombian electro-pop ✦

The online magazine passerby invited me to be the guest curator for their November recommendations. It was the perfect opportunity to write about anti-algorithmic music discovery, perfumes I love, and more:

If the music recommendations in there aren’t enough, here’s one more: the Colombian singer–songwriter–producer Ela Minus. Her album DÍA is full of gauzy, shimmering synth sounds, with her languid, ethereal voice threading through.

Thank you, as always, for reading this newsletter! And congratulations to everyone in NYC who canvassed for Zohran this summer and autumn. It’s invigorating to see political change happen through sheer force of will and enthusiasm. As Sarah Thankam Mathews wrote back in June, “Enough pessimism of the intellect, it is time for my new best friend: optimism of the will.”

I don’t mean to say that Gilda William’s How to Write About Contemporary Art is a bad book. It’s excellent—and useful for experienced critics, too, as Andrew Berardi observed in a Momus essay:

Though clearly written for neophytes, you wholly delight in the deft simplicity in which Williams explains the hot mess of the artworld and how underpaid writers might somehow navigate it with only words. You find her history of art writing beautifully concise, collapsing your years of subtle research into pages. Much of the text, however, though it uses examples from art writing, could just as easily be said about all writing.

But it turned out to be easier for me (and maybe for others, too?) to first read examples of great art writing—and what to strive for—before picking up a how-to.

In 2023, Albert Riera Galceran and Reuben Beren James, the cofounders of émergent, were interviewed about their approach to curating “known” versus “unknown” artists:

The art market can be highly competitive and profit-driven. How does émergent navigate the balance between showcasing commercially successful artists and promoting more unconventional or experimental forms of artistic expression?

We consciously disregard those categories and sort of accidentally merge the relationship between the “known” and the “unknown”.

Terms like blue chip make our skin crawl…Commercial success is not only an inaccurate metric for artistic validity or success, but it’s also pretty short-sighted from an art historical perspective, there is an inherent intergenerational relationship between younger, more emerging artists, and their “commercially successful” predecessors, and that discourse should be explored, it’s important to engage with the influence and evolution of ideas between all these artists regardless of stature. So we don’t really consider it, we sit down and try and curate the perfect selection of artists and artworks that speak to each other, and they seem to balance themselves out on their own I guess.

"Ghosts of My Life tucked into a bed" - it's all too much

Thank you for sharing this! Going to try and catch Kwak Kyung-tae's show before it ends.

Not exactly under the radar, but I finally went to the Giacometti x Mona Hatoum exhibition at the Barbican and loved it - beautiful and haunting. (That’s the limit of my art-writing skills.) If you haven’t seen it yet, I’d highly recommend!

Last thing - beyond happy to see a shout out to perfumer/DJ extraordinaire and kindest soul David!! Love a little reminder of how small the world can be.

always so inspiring to read your words! also got really excited by the perfection cover - i haven’t seen this one before but i thought it captured the messiness and dimensionality of the protagonists’ lives beyond the flat facade they put up quite well