mere description

it's harder than it looks to simply describe what we see ✦ Brian Dillon, Lauren Oyler on criticism ✦ character and nature, by Olga Tokarczuk and Mircea Cărtărescu ✦ attempting to write about music

We describe things. All the time. And those descriptions can be ordinary, unremarkable, obvious—or they can be strange, surreal, exciting, unexpected. When I write I’m always trying to do the second kind of description (good, interesting, literary description) and avoid the first. But it’s hard to describe things well, like really well. And lately I’ve been thinking that my fear of ordinary description is the problem.

“Observe…more slowly, almost stupidly”

I’m still reading The Everyday, the contemporary art anthology I wrote about in my last post. This week I came across a passage from the French novelist and essayist Georges Perec. He describes, in playfully deliberate detail, a particular street in Paris. Then he explains his approach towards writing:

Observe the street…Note down what you can see. Anything worth of note going on.

Do you know how to see what’s worthy of note?

Is there anything that strikes you?

Nothing strikes you. You don’t know how to see.

You must set about it more slowly, almost stupidly.

Force yourself to write down what is of no interest, what is most obvious, most common, most colourless.

What struck me was this advice: Nothing strikes you. You don’t know how to see. You must set about it more slowly, almost stupidly. We think we know more than we do, understand more than we do, until we describe it.

I was talking to a friend about Renoir yesterday, so let’s take Renoir’s famous Luncheon of the Boating Party painting as an example. What do I see? A group of people having lunch. Wait, but do I know they’re having lunch because of the title has luncheon in the name, or because it looks like lunch? I see wine bottles, a bowl of fruits with the grapes spilling over the edge, empty plates and cups.

There’s so much more to describe. Everyone in it is white. (Probably.) They’re dressed in white and navy, mostly, but there’s a man to the right whose jacket is—how would I describe it? Is it meant to be a pale yellow with black pinstripes? And now that I’ve tried to describe the colors, I’m noticing the man in a brown jacket, the man in the very back of the—I mean, what are they on? A terrace or veranda (I could have said “patio”, too, but I don’t like how that word looks as much) with that stripy covering—is there a name for that kind of thing? You know, the stripy…fabric…???

Slowly, almost stupidly, I look at the painting, I pay attention, I try to understand what I’m seeing.

“Mere description”

Perec’s advice reminded me of something Brian Dillon, the critic and essayist, said in an episode of the Fitzcarraldo podcast this summer. Dillon writes literary criticism ad art criticism, and he has 3 books of criticism: Essayism is about essays, Suppose a Sentence about sentences, and Affinities—the most elliptical title—about art and photography, mostly. When writing, Dillon said:

I realized…that the really exciting thing was literally to try and describe what’s in front of you. That’s very arduous. I had been trained in a kind of intellectual tradition, a critical tradition, that saw description as “mere” description. And I think I’ve always been keen, when I see that description of something as “mere”—I’m on the side of “mere”, I empathise, I sympathise with the “mere”…How do you describe a form, how do you describe a body, how do you describe a thing?1

Mere description: it’s harder than it looks! But how do we get any good at it?

I keep on thinking about the advice that the critic and novelist Lauren Oyler shared in “How to Criticize”, a hybrid lecture delivered at the American Library in Paris (and over Zoom, which is how I attended). She began by describing, at a high level, what the work of a critic is:

The first step in criticism is paying attention…and then understanding what you think about the things you notice…

A work of art, or literature, or whatever you're looking at, is made up of many many many little choices…Is it fiction or nonfiction or poetry? Is it 5,000 words long or 200,000 words long?2…Why is that comma there? Why do you have a run-on sentence there?

…Some of the choices an artist makes are conscious, some are unconscious…As a critic you have an easier job. You just have to notice the choices the writer has made.

Oyler then gave us the following exercise: “Think about something that you've read or watched recently, and try to describe it objectively to someone who's never heard of it.” We did it twice: first with something we loved, and then with something we hated. The point of the exercise, Oyler stressed, was to not reveal our subjective impression of it—if possible.

I tried describing a novel—Olga Ravn’s My Work—as plainly and clearly as possible. (I’m writing a review of My Work; it should be published soon, and I should be able to share it soon!) And I realized all over again that it’s hard to describe what a novel is about, what its themes are. What seems like mere description is actually something that requires all of my interpretive and critical faculties.

When I wrote the first draft of my Mild Vertigo review, I was obsessed with the idea of having a Strong Opening at the start—to be followed by a Brilliant Analysis of the Themes—and a Stylistically Innovative Closing. But after I submitted my first draft, my editor got back to me with very encouraging, very helpful feedback that included the following:

I'd rewrite the intro a bit, so that it includes a little more about the author, a more measured synopsis of the novel (timeframe, characters, etc.)…I'd like to see a more deliberate exposition of the novel.

In my attempts to do interesting, elaborate things in my review (I was going to write about Roland Barthes’s ideas in relation to the novel! I was going to reflect on women and domesticity and household labor and consumer culture!) I had forgotten about the very basic, almost rudimentary description that a review needs to have. Who and what is the book about? Where does it take place? I’d explained a bit of this, but not very clearly and not very well.

So I rewrote the intro, as suggested, and the review became much better. A little bit of exposition—and then I could get to all the other things I wanted my review to be about. It seems so obvious and banal, to write something like: This is a book about a woman living in a Tokyo suburb with her husband and two children. But that context sets up everything else.

I realized this again when a friend shared a draft of a film review with me, and I noticed she’d done the same thing I did—leapt into a really lovely, atmospheric, perceptive analysis of particular scenes in the film, certain moments—and yet the basic housekeeping (who and what and where?) was hard to find. I told her what my editor had told me. Her second draft was great, really great, and I’m looking forward to reading the final review.

Mere description: it’s easy to forget about! But it’s worth it.

Very, very good descriptions

The goal, of course, is for mere description to become more than that. Even a functional description can, in the details it includes and the specificity of those details, become beautifully expressive.

A beautiful example of this comes from Flights, a novel by the Nobel Prize in Literature laureate Olga Tokarczuk. Before I tell you anything about the novel, let’s start with how the narrator of Flights is described:

I have a practical build. I’m petite, compact. My stomach is tight, small, undemanding. My lungs and my shoulders are strong. I’m not on any prescriptions—not even the pill—and I don’t wear glasses. I cut my hair with clippers, once every three months, and I use almost no makeup. My teeth are healthy, perhaps a bit uneven, but intact, and I have just one old filling, which I believe is located in my lower left canine. My liver function is within the normal range. As is my pancreas. Both my right and left kidneys are in great shape. My abdominal aorta is normal. My bladder works. Hemoglobin 12.7. Leukocytes 4.5. Hematocrit 41.6. Platelets 228. Cholesterol 204. Creatinine 1.0. Bilirubin 4.2. And so on. My IQ—if you put any stock in that kind of thing—is 121; it’s passable. My spatial reasoning is particularly advanced, almost eidetic, though my laterality is lousy. Personality unstable, or not entirely reliable. Age all in your mind. Gender grammatical. I actually buy my books in paperback, so that I can leave them without remorse on the platform, for someone else to find. I don’t collect anything.

In this highly specific, highly dispassionate description of the self, we learn quite a bit about the narrator. A woman (petite, not on the pill: only women describe themselves with these details). Capable of cool self-assessment (teeth: healthy, IQ: passable, personality: unstable). Some personal interest or professional expertise in the body, because she specifies a filling in her lower left canine, not just a tooth.

What kind of character introduces herself by telling us about her hemoglobin levels and leukocyte count? The central character of a novel that, as it unfolds, is obsessed with the body, with how the organs function (or don’t), the medical interventions that can extend or shorten life, the ways in which bodies are preserved after death. The novel follows this unnamed woman through various airports as she visits museums devoted to anatomy and the body. Later on in the novel, the narrator asserts that “Every body part deserves to be remembered. Every human body deserves to last. It is an outrage that it’s so fragile, so delicate.” This ideal is reflected in how the narrator describes herself—in her intense concern with the mechanics of her own body.

Equally striking are Tokarczuk’s descriptions of the world. Tokarczuk was a poet first, actually, and published a poetry collection before turning to the novels that made her famous in Poland and then the world. And you get a sense of that poetic background in the great economy and beauty of descriptions like this:

A crisp morning, the streets are lively, sunrise, the sun’s disk scraped up by slender poplars—it’s a pleasant walk.

This description is seared into my memory. Ordinary descriptions—a crisp morning, a pleasant walk—bracket an extraordinary poetic image: the sun’s disk scraped up by slender poplars.

By sheer coincidence, I was revisiting some quotes I’d saved from the Romanian novelist Mircea Cărtărescu’s novel Solenoid, which I read a few months after Tokarczuk’s Flights. It turns out Cărtărescu included a very similar image in his novel as well:

Black tree branches scraped against the intensely blue sky, and all the trees were dead—as though they had never lived.

It’s a more somber description, of course—the black branches of dead trees—but it feels so rare and unexpected that both of these novelists have described trees scraped up/against the sun (Tokarczuk) or sky (Cărtărescu). It’s a great verb, scraped. Mostly deployed to describe scraping your knee, scraping the burnt bits off a pan, scraping ice off of a car windshield. An ordinary verb, turned towards extraordinary purposes by these two writers.

Let’s talk a bit more about Cărtărescu’s novel, because it’s one of the best books I read in 2023, and it’s full of brilliantly evocative descriptions as well. Here, for example, is how Cărtărescu’s narrator, a young Romanian schoolteacher, describes himself while taking a bath:

My hair spreads toward the sides of the bathtub, like a blackbird opening its wings. The strands repel each other, each one is independent, each one suddenly wet, floating among the others without touching, like the tentacles of a sea lily. I pull my head from one side to the other so I can feel them resist; they spread through the dense water, they become heavy, strangely heavy.

Through this, we learn quite a bit about this man. He’s obsessively concerned with the minute perceptions and sensations of life. Exhaustively detailed in his observations. Given to flights of imagination, naturalistic ones (his hair is compared to a blackbird opening its wings, and later to the tentacles of a sea lily). Oriented, perhaps, towards depression (his hair is heavy, strangely heavy). The novel eventually informs us about the narrator’s surreal dreams and nightmares; about the fear and fascination he feels towards his body; about his intense love for nature; about the unyielding despair of his childhood and early adulthood. And again, all this is introduced in the small choices Cărtărescu makes in this description.

I recommend Tokarczuk’s Flights and Cărtărescu’s Solenoid unreservedly, by the way. They’re two of the greatest novelists of our time, I think. Their novels are wide-ranging and inquisitive novels, pairing big themes (Tokarczuk: the history of medicine, colonialism/imperialism; Cărtărescu: Boolean algebra, Communism and national identity) with the small moments of life.

They’re both novels centrally concerned with the body, but I don’t know if I’d describe them as embodied narratives, really. The protagonists observe their own bodies very carefully, but I don’t know if they live within them. Rather, they live within a mind that is fascinated by all the grotesque, elaborate procedures of the body. “It seems strange that I have a body, that I am in a body,” says the narrator of Solenoid.

And the way they describe things! The entire ethos of each novel is apparent in just a single paragraph about a body, a single sentence about the trees and sky. That’s what great description does: it compresses a highly unusual, highly idiosyncratic point of view into the smallest observations about the world. Writing might begin with mere description. But really great, moving writing rarely contains itself to the mere.

Four recent favourites

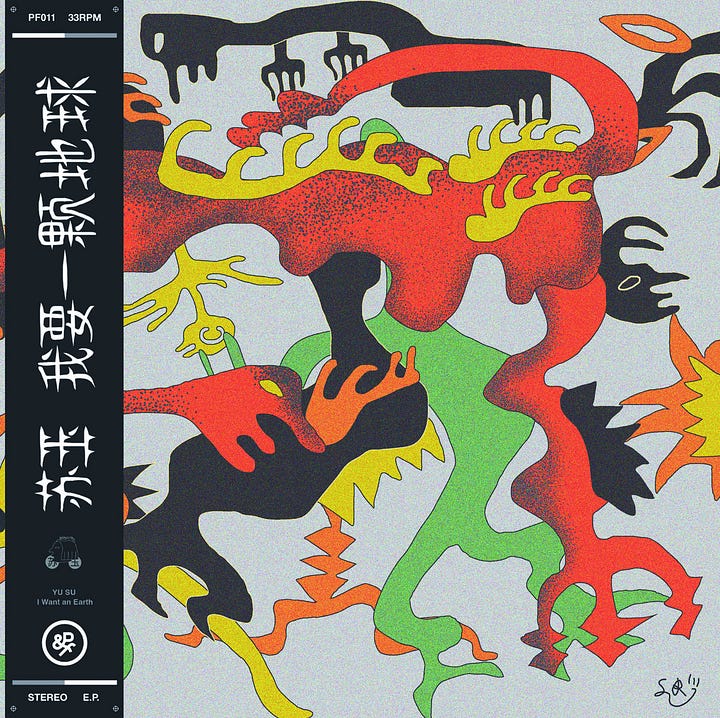

Critical theory, explained ✦✧ Best fashion books of the 2000s ✦✧ Tuberose, maybe the best fragrance in the world? ✦✧ Yu Su’s experimental dance music

Finally, someone explains critical theory and the Frankfurt School to me ✦

Speaking of description—I started reading Stuart Jeffries’s Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School, a highly readable and very fun group biography of the German intellectuals, philosophers, and writers associated with the Frankfurt School. You know, those guys: Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, Max Horkheimer…the critical theory guys.

What has always intimidated me about critical theory is the highly academic, opaque language it seems to involve. Grand Hotel Abyss is great because it’s so clearly written and therefore very welcoming to readers. Here, for example, is Jeffries trying to summarize the

Why was socialist revolution increasingly unlikely in the 1920s? Because the reified structure of society, the alienation of workers and the commodity fetishism of the modern world was so complete that they militated against the class consciousness necessary for such a revolution.

But what do those terms mean? Alienation? Reification? Class consciousness? Commodity fetishism?

What do they mean? Jeffries goes on to very carefully and lucidly explain all 4 terms, and now I finally get what people mean by reification. Sometimes people write about critical theory and don’t define any of this, and I assume it’s because they think their audience already knows what’s going on. But I suspect that, at least some of the time, it’s because trying to explain these very central terms is actually quite hard, and writers would rather avoid the task and make the reader feel embarrassed instead.

Why fashion is getting so expensive ✦

Now on to commodity fetishism. In one of Amy Odell’s latest Back Row posts, she describes how aspirational shoppers—people like me, who can afford designer clothing sometimes and certainly aspire to buy it, but are also constrained by, you know, a budget!—are buying less designer fashion. Luxury brands are responding by trying to sell more to an ultra-wealthy market.

The rest of the post is an interview with the great fashion journalist Dana Thomas , whose book Deluxe: How Luxury Lost its Luster (2007) is “the seminal Y2K book on how the [fashion] industry works”. I read it a few years ago, along with Thomas’s other books: Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano (2014), which also portrays the London fashion scene and Parisian couture from the 1990s–early 2000s; and Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes (2019).

I love Thomas’s writing because she moves easily between the aesthetic and affective side of fashion—what do the clothes look like? why were they so remarkable for their time?—and the financial and business side of it. More books on the business side of things: Trading Up: Why Consumers Want New Luxury Goods (2003), which is written more for marketers and entrepreneurs but is fascinating to read as a consumer of fashion; and Teri Agins’s The End of Fashion: How Marketing Changed the Clothing Business Forever (1999). Agins was a longtime fashion writer for the WSJ, and like Thomas does a great job of combining fashion-as-art with fashion-as-business.

When people complain about how the quality of clothing today is just so terrible, things are getting cheaper and cheaper, trends are moving faster and faster—these aren’t things that started happening in the last two or three years, lol. They’re really long-running trends! And much easier to understand with these books.

Tuberose’s number one fan ✦

It’s December in northern California, which means it is very slightly cold. But I’m leaning into cold weather rituals anyway, like burning candles at home.

All summer I was wearing a tuberose-forward perfume, Frédéric Malle’s Carnal Flower. I love tuberose: it has the open, full, intoxicating strength of jasmine, but mediated with a cool menthol-y note. For winter I’ve been burning D.S. & Durga’s Rama Won’t You Please Come Home candle, which is also a tuberose scent—but with a lovely, warm sandalwood note as well.

My apologies for acting as an unpaid advertisement for a consumer good…right after recommending a book about the high cost of consumption…and right after recommending a book about a bunch of Marxists…

Yu Su’s debut album ✦

Last week at work we did a little playlist exchange (I know! very cute!) and I ended up making a playlist for a coworker with 2 tracks from Yu Su’s debut album, Yellow River Blue (2021). It’s a great album—it was very, very hard for me to not add a 3rd song in.

Yu Su describes herself as a “Kaifeng-born, Vancouver based musician, DJ, sound artist, and occasional chef”. In an interview with Mixmag from earlier this year, she described her childhood in China, where she learned to play piano and falling in love with the Hungarian composer Liszt, and leaving in 2014 to go to university in Vancouver. That’s where she encountered dance music:

At that point I’d never been to a dance music party. I just had no idea about anything – nothing…So imagine me going sober, everyone is on a completely different frequency, I had no idea about drugs or rave culture and I had to stay to the end because I was too scared to leave by myself…

[B]y the end of the night – because I was just like ‘I don’t understand this music, I can’t tell you where it’s from’, I got so sucked into it…it was just so interesting.

She learned to produce, learned to DJ, cofounded bié Records to put out her music and the work of other Chinese artists, and in 2021 released Yellow River Blue.

How to describe the music? Avant-garde, ambient/downtempo, experimental dance music with unusual instruments and sounds drawn from traditional Chinese music. This is a useful description, but it also feels a bit keyword-y, like I’m describing the album for a search engine and recommendations system.

Let me try again. It’s music you can dance to or simply sit and encounter with deep attention. There’s exuberant instrumentation, ethereal vocals. A beat is always present, but sometimes it submerges itself underneath more fluid, stretched sounds. To listen closely, with your full attention, is intensely rewarding because it’s so layered, with an eclectic variety of sounds moving in and out—light percussive beats that seem to catch on the air; deeper, more resonant beats that feel more grounded; the warmth and tactility of piano keys; and then a shimmering, lighthearted synth…

I’m particularly intrigued by “Klein”, which opens with a very quiet, unsettling buildup of industrial sounds—but they feel beautiful; they’re laced through with these high, sharp sounds that sound like cyborg birdchirps—and then vocals that feels a bit like a slow, reverent chant from a Buddhist nun are pulled into the track—and then a slow, deliberative beat with an almost chopped and screwed quality.3

That’s all for today. Back to reading, back to listening, back to paying attention to the world and its cultural works. Until next time!

This quote starts from around 22:05. I’ve taken some liberties with my transcription of Brian Dillon’s words—striking out things like And, And I think, And so…

I can’t quite remember the exact numbers Oyler said. Was it 5,000/200? 50,000/20,000? I might be misquoting her…but not egregiously! The point still stands!

One of the downsides of having a lot of Friends Who Are Into Music is that I never quite feel at ease writing about music. I don’t DJ, I don’t produce, I don’t play an instrument. It very much feels like I am missing some essential lexical repertoire that might allow me to really describe what’s going on, what an artist is doing to and with sound. But I’m experimenting—this Substack is for experimenting—and it was, in the end, really nice to try and write about Yu Su!

"it’s hard to describe what a novel is about"---I think this is *the* biggest challenge. I was told, aged 16~, to read The Handmaid's Tale. I asked what it was: "Canadian, feminist, sci-fi." No thanks! Turns out, it's one of the best novels ever and you can say *so much* that isn't that... so many novels have this problem. I'm reading Atlas Shrugged right now and... no-one told me how much fun it is!

i really loved reading this