everything i read in september 2025

novels & nonfiction about AI poetry, lost love, corporate anthropologists, and more ✦

The plan was to read Schattenfroh. I was going to have a Schattenfroh September, beginning on Tuesday the 9th, when the thousand-page novel—by the German writer Michael Lentz, and translated by Max Lawton—was published in the US. For the unreformed brodernists among us, this was meant to be the literary event for the season (until, at least, the 3rd volume of Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume is published in November).1

September did not go as planned. About 68 pages into the novel, I realized that I really didn’t want to read another experimental European novel with a tormented narrator reflecting on language, daddy issues, the trauma of WWII, “the real,” presence and absence in the archives, and lists of the dead. I set the novel aside. I might return to it in October or November—too late for the alliteratively appealing Schattenfroh September, just as I was too late for Middlemarch March (I was reading Annie Ernaux instead).

Instead, I read:

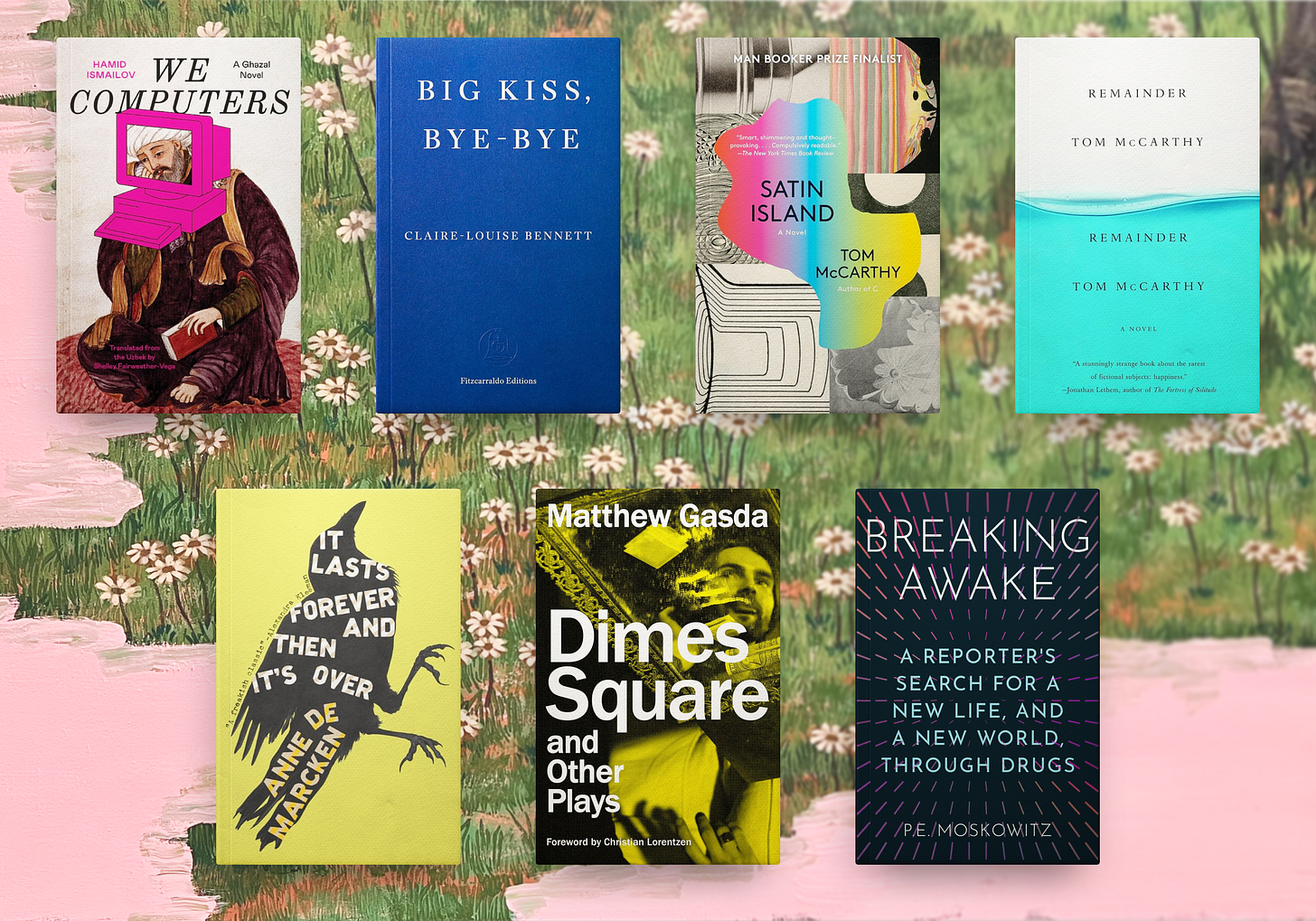

2 other newly published novels (Hamid Ismailov’s We Computers and Claire-Louise Bennett’s Big Kiss, Bye-Bye)

2 books by Tom McCarthy, including Remainder—which Zadie Smith described as “one of the great English novels”

A literary zombie novel that made me cry

P.E. Moskowitz’s excellent new book about how we (as individuals, and as a society) use prescription and illicit drugs for mental health

The original MFA discourse book2

And Matthew Gasda’s Dimes Square and Other Plays

September was also the month that personal canon received two small press mentions—

My newsletter on expanding the market for literature is quoted in Molly Templeton’s column for Reactor, formerly Tor, on the recent conversations about the “death” of criticism. She also discusses the novelist and essayist Patrick Nathan’s excellent and invigorating essay on the future of criticism!

And last year’s newsletter on 13 propositions for AI art is quoted in Lucas Gelfond’s essay for Spike Art Magazine on artists making work with AI

But that’s enough self-promotion for now…on to the books!

Novels

Two very new novels about AI, poetry, and kissing

It seems appropriate that I read Hamid Ismailov’s We Computers: A Ghazal Novel (translated from Uzbek by Shelley Fairweather-Vega) while back in SF for 2 weeks, in the shadow of the city’s strange AI startup billboards. (I recommend Wendy Liu’s excellent billboard criticism column for Bay Area Current.) Ismailov’s novel, longlisted for the National Book Award in translated literature, is about a French poet-programmer who becomes obsessed with using his computer to generate literature. We Computers is tremendously funny and charming (I read it in one sitting) and one of the most original, sideways explorations of how AI will affect literary authorship and innovation. And it’s especially enjoyable to read if you’re curious about Persian poetry, and the 14th century poet Hafez especially.

Once I was back in London, my friend Cara and I went to the LRB bookshop for an event with Claire-Louise Bennett and Devorah Baum. The occasion was, of course, the publication of Claire-Louise Bennett’s Big Kiss, Bye-Bye. I’ve been a huge fan of Claire-Louise Bennett ever since my friend and former flatmate, Harri, lent me a copy of Bennett’s Pond in 2020. (I later included it in my Atlantic article about six great short story collections.) Bennett writes with mesmerizing phenomenological intensity—her second book, Checkout 19, has some incredible passages about the feeling of reading a book, and the texture of one’s physical and psychological experience. Big Kiss, Bye-Bye turns this introspective, observational acuity to the story of a woman contemplating the end of a relationship with a much older man—and the various entanglements and liaisons she’s had in her life. There are some very cute lines about the passionate langour of spending all afternoon lying around, kissing a loved one. There’s a very good sex scene. There are multiple, very good scenes of her obsessing over the contents of an email. It’s funny and charming and sad. It’s excellent!

I just adore Bennett as a writer—and if you do too, you might also like:

The artist and critic Audrey Wollen’s excellent review of the book, which touches on all the texts and emails that get drafted/sent/read/replied to in Big Kiss, Bye-Bye. “The epistolary novel,” Wollen writes,

should probably be the dominant form of our historical moment…After all, epistolizing is what many of us spend most of our time doing: reaching out, circling back, saying hi, jostling between the telegrammatic fizz of the text message, the courtly tones of the business email, the lackadaisical skywriting of social media, and so on.

On The Yale Review’s Substack, there’s also an interview with Wollen about the best/worst writing advice she’s received, and more.

The writer and researcher and friend-of-the-newsletter Phillip Maughan’s 2016 interview with Claire-Louise Bennett in the Paris Review, where Bennett says:

I respond to atmosphere much more than plot, say, and it seems it gathers much more effectively around a lone voice, just like it does around a single candle flame perhaps. I’ve always been drawn to the misfit, the outcast, the exile, the hopeless case with the wicked sense of humor—I’m thinking of narrators in work by Samuel Beckett, Jean Rhys, Marlen Haushofer, Thomas Bernhard, Clarice Lispector…Basic life situations, such as marriage, work, procreation, don’t occur automatically for some people and it’s desirable that fiction reports upon the lives of so-called outsiders because actually when you spend so much time alone you are kind of starting from scratch, on your own terms more or less, every single day, and it’s nullifying and terrifying and occasionally glorious.

Two paths for the novel

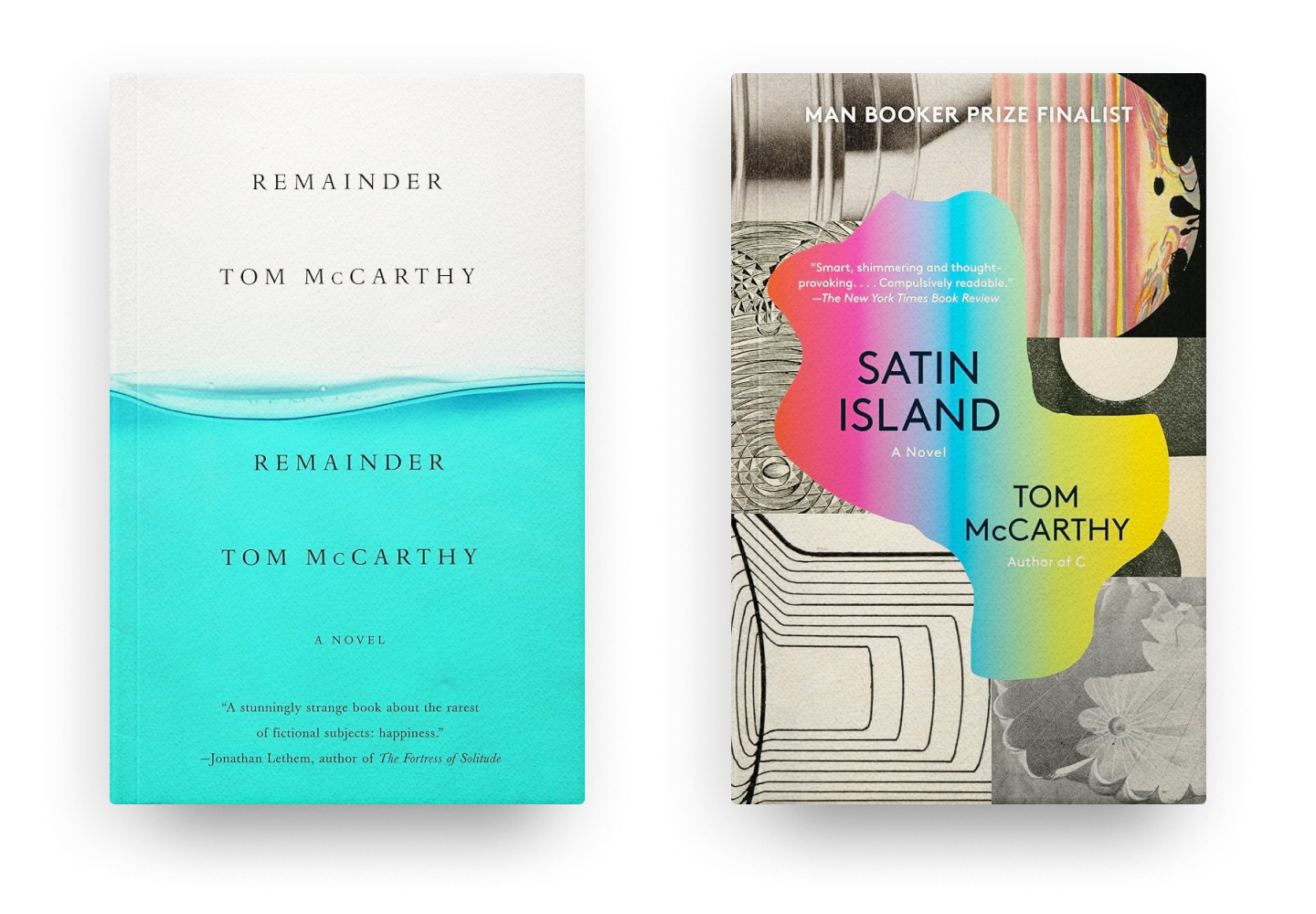

For years now, I’ve been seeing essays titled “Two Paths for the X.” (Like for the personal essay, or for AI.) In early September, I realized that these titles were likely modeled after an influential essay by Zadie Smith, “Two Paths for the Novel,” published in the NYRB in 2008. In it, she praises the writer and artist Tom McCarthy’s Remainder by saying

It works through the things we expect of a novel, gleefully taking them apart, brick by brick…We could call this constructive deconstruction, a quality that, for me, marks Remainder as one of the great English novels of the past ten years.

So what is the novel about? Well. Imagine you’re a man who has enough money (£8.5 million, to be precise) to never have to work again. Imagine, also, that you received this money not through the usual means—a trust fund, say, or a successful startup IPO—but through a legal settlement, after experiencing a traumatic injury that left you bedridden for months and with much of your memory erased. What would you do with your life? Well, if you’re the protagonist of Remainder, you realize that the only thing that makes you feel good is the occasional, tingling feeling of déjà vu when something reminds you of the past. So you hire an abnormally competent right-hand man named Naz and start orchestrating extremely complex reenactments of certain scenes—half-remembered, actual, fictional—involving paid actors and purpose-built settings. What kinds of scenes? Oh, you know, shootings and bank robberies; nothing major.

Remainder is just phenomenal. When I finished the novel—caught up in the sheer extravagance and drama and energy of the ending—I told my flatmate, “I feel so caffeinated right now! Like I’ve just had an espresso shot!” He said that’s what it feels like when you read a novel with actual plot.

I then read Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island, which has a somewhat more sedate pace (though I found it, personally, still very thrilling—I finished it at 1am on a weeknight). It’s a novel about a cultural anthropologist who, after finishing his PhD, ends up working at a mysterious and chic strategy/consulting/branding firm (in my imagination, it was something like IDEO, but led by a Steve Jobs/Brian Eno–style figure). He aspires to do work on the level of Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques, but he mostly spends his days printing out photos of oil spills and vainly trying to be a thought leader. It’s a very funny depiction of the opacities of corporate life!

Life after life

Then last weekend, while taking the overground from east London to south London, I started and finished a slender, 132-page novel: Anne de Marcken’s It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over, which won the 2024 Ursula K. Le Guin Prize for Fiction. De Marcken’s novel is about an undead woman reminiscing about her past life, while grappling with the everyday challenges of being a zombie. Her arm falls off (painlessly but inconveniently, since she can’t tie her shoelaces anymore). An acquaintance starts preaching to the other undead. At least, the narrator thinks, “it’s something to do in between killing and eating.” What she dislikes about being undead, she thinks, is that:

Undifferentiated time is the worst. There are no more three-day-long days.

I tell Marguerite about three-day-long days. The last one I remember was the summer before the last summer. We were having a dinner party…You cleaned and I cooked…Afterward, you kept me company outside while I had a cigarette. There was a nearly full moon that night…

There are no more three-day-long days. That feeling of abundance depended not upon excess and not scarcity, but finitude and a kind of thrift. It had to do with there being only so much time in the day but still more than just enough and using up every ounce of it, not wasting a moment.

This concept of abundance-as-finitude reminds me of one of the more elegant observations in the producer Rick Rubin’s The Creative Act, a meandering book of creative advice that could have used a much tighter edit. But I don’t dislike it; some of the ideas in it have become very precious to me, like this:

Discipline is not a lack of freedom, it is a harmonious relationship with time. Managing your schedule and daily habits well is a necessary component to free up the practical and creative capacity to make great art.

Which makes me wonder: would the undead be capable of producing great art? Or does artistic discipline come from knowing that your life is finite and you only have so much time to leave a mark on the world? I’m happy that de Marcken left this small mark on the world, at least—it’s a beautiful novel. I’ve been meaning to read It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over ever since Jon Repetti ’s wonderful newsletter about the novel—I’m very happy I finally got around to it!

Nonfiction

I’ve spent the last 2 years awaiting the journalist P.E. Moskowitz’s Breaking Awake: A Reporter’s Search for a New Life, and a New World, Through Drugs. Moskowitz’s previous book on gentrification, How to Kill a City, was incredible—insightful, meticulously researched, a really ideal balance of personal narrative and reporting.3 I really trust Moskowitz to take on big topics (free speech, gentrification, and now mental health/psychiatric treatment) in subtle and interesting ways. Breaking Awake is great. It opens with Moskowitz’s own struggles with trauma and recovery after the Charlottesville attack in 2017, and elegantly incorporates their investigations on how we depend on drugs, both psychiatric and recreational, to cope with difficulty in our lives.

It’s a really capacious book: Moskowitz takes on drug addictions, harm reduction efforts, the mixed research on the efficacy of many psychiatric drugs, opiod usage, and more. It’s a hopeful book, but it resists a linear path towards resolution—here’s a trauma, here’s how it was resolved, here’s the drug that made everything better, end of story. To me, that makes the book a more grounded and intellectually honest.

On a more frivolous note: I also read the essay collection MFA vs NYC: The Two Cultures of American Fiction, published by n+1 and edited by Chad Harbach. Every so often I find myself fascinated by MFA discourse—whether the creative writing MFA has had a positive or corrosive impact on American fiction. And it’s intrinsically fascinating to read about how writers make money (or don’t). The standout essay in MFA vs NYC, in my opinion, is Eric Bennett’s “The Pyramid Scheme,” which describes Bennett’s experience at the famous Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and then his experiences researching and writing a book about how the CIA helped fund some of America’s most renowned literary institutions. “The idea seems like the invention of a creative writer,” Bennett notes, but it was part of a larger project to promote American individualism and capitalism during the Cold War. What makes Bennett’s essay so wonderful is the way he characterizes his writing teachers and other influential figures in American writing. Here’s how he writes about Frank Conroy, who led the Iowa program when Bennett was a student:

[Conroy’s] force of personality exceeded his sweep of talent—and not because he wasn’t talented. By the time I met him he had entered the King Lear stage of his career. He was swatting at realities and phantoms in a medley of awesome magnificence and embarrassing feebleness. His rage and tenderness were moving. I adored him. He was a thunderstorm on the heath of his classroom, and you stepped into his classroom to have your emotions buffeted for two hours.

Plays

I also read Matthew Gasda’s Dimes Square and Other Plays because I was planning to book tickets to see another Gasda play, Doomers (which is inspired by Sam Altman’s short-lived ouster from OpenAI). I failed to book the tickets (I’m eternally missing out on things because of my own disorganization), but I did enjoy reading Gasda’s other work! Dimes Square, which features a loose collection of friends and lovers and rivals meeting at an apartment in NYC’s Chinatown, has excellent and truly entertaining dialogue. I expected it to be insufferably ironic, but Gasda strips down the nervous posturing of its characters to reveal an edge of desperation in everyone: desperation to be seen, to be affirmed, to make their mark on the world, to be accepted. I liked the last play, Berlin Story, too—it features a few different not-quite-couples who can’t quite align on what they want from each other. It’s a funny and touching story about people reaching, constantly, for the security that love or sex or both at once can provide, and not quite getting there!

Gasda’s plays ended up feeling more interesting and subtle than his public persona—I’m borrowing this observation from the Boston-based critic Michael Patrick Brady, whose (largely positive) review of Gasda’s debut novel, The Sleepers, has some excellent observations about ideology in art:

Last November, Gasda spoke at an event in Brussels where he talked about being shut out of the New York theater establishment because his work was “not explicitly ideological.” He says he believes there needs to be space in art and theater to interrogate a broad array of views and that it shouldn’t be purely activist in nature. I’m sympathetic to that, I suppose, in that I find overly didactic art is usually pretty weak…

However, he also references “[his] constant refusal to declare himself [in the culture wars].” He said this at the Mathias Corvinus Collegium, an educational institution with close ties to Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban…

I get it—if your perspective is that art shouldn’t be political, you aren’t going to get invited to a lot of leftist or progressive spaces. The fact that you will get invited to a lot of expressly right-wing or reactionary spaces, however, should probably serve as an indicator that your non-political perspective is, in fact, quite political.

Art

Earlier this year I was obsessed with the idea of “model collapse,” a phenomenon where AI models that are trained on too much AI-generated text (instead of purely human-created text) exhibit “irreversible defects,” according to a 2024 Nature paper. The artist Felicity Hammond’s V3: Model Collapse, an exhibition that just closed at the Photographers Gallery in London, explores how a model trained on Hammond’s photographic datasets (collected from her previous exhibitions) can create strangely alluring, degraded and distorted visuals—as it’s trained on more and more AI-created imagery.

I loved the generated images—where photographic realism and jagged digital artifacts press up against each other—and I loved how they were installed in very physical structures, which emphasize the materiality of all the rare earth minerals that need to be mined for our computing needs.

After seeing Hammond’s work, I walked over to the Royal Academy for the American painter Kerry James Marshall’s Histories exhibition. When I wrote a newsletter about Marshall last year, I hadn’t seen any of his work in person—

—and it was really a revelation to encounter his enormous, opulent, saturated canvases in person. The scale of his paintings is extraordinary. And in person they’re so much weirder and stranger than I expected. Yes, he’s a figurative painter that has, for many decades, resolutely devoted himself to Black portraits and Black American life—but this description, for some reason, made me expect very traditional and realist paintings.

But in paintings like Past Times, which depicts a family lounging around in a Chicago park, there are details like the crisp white strokes of a golf club’s swing, and and the physical presence of music emanating out, like sheer satin ribbons, from the radios:

I was fascinated by this painting! I couldn’t stop staring at it, and it kept on feeling stranger and weirder and more engrossing as I did. I had the same experience with School of Beauty, School of Culture, where—in the middle of a busy, glitzy beauty salon, two young children are inspecting a strange, distorted head in the middle of the room. The head made me think of the little coins and resources that get scattered around the landscape of a videogame. (A friend later told me that it’s a reference to the similarly distorted, anamorphic skull in a famous Hans Holbein painting.)

Articles

I’ll close with some of my favorite articles, essays, and newsletters from the month:

Have the courage to be truly pretentious! Emma Withers’s music newsletter has it all: excellent playlists, reading recommendations (on Brian Eno, ‘70s punk bands, and interior design inspiration), and charming commentary on Wikipedia’s impact on the 21st century hipster:

In 2001 Wikipedia launched, and it is likely that it is somewhat responsible for the unendurable rise of the hipster in the early 2000’s. Suddenly we were all sitting around asking people if they had heard about the Dyatlov Pass incident. We were shunning those who did not know about “The Silent Twins” or Rosemary Kennedy’s lobotomy…When used by a tasteful and brave master ie you, it can truly allow you to be the most annoying, fascinating, pretentious version of yourself. Have the courage to make an article you like your personality, do not be afraid to destroy a dinner party by talking AT LENGTH about an unsolved mystery at sea, insist upon playing that incredible field recording you came across on Youtube to all your friends! It’s your internet, use it well!

An art magazine? In this economy? Charlotte Klein, the media columnist for New York Magazine, on the sudden rise of Cultured. A fascinating look at a magazine I’ve started reading religiously—because they have Johanna Fateman writing art criticism and convene exciting roundtables (like Vanessa Friedman, Tim Blanks, and Rachel Seville Tashjian discussing the state of fashion criticism).

The publishing industry has a gambling problem. Tajja Isen (a tremendously insightful and elegant writer; I’ve actually copied some of her paragraphs into my notebook to study how she does it!) on the publishing industry’s faulty attempts at data-driven decisions. One of the many fascinating insights in Isen’s article is that an absence of data on a debut writer’s sales becomes more promising to publishers than an established author’s midrange sales.

Being trailed by one’s sales data gives first-time writers a certain advantage. Debuts are deeply attractive to publishers because, as writer and researcher Laura B. McGrath puts it, “there is nothing but potential. If your track is zero, there’s only one place for it to go.” The book’s advance is therefore set by anticipation—the publisher’s bid is roughly commensurate with how big they think they can break it out. They reach this number by assigning a value to what McGrath, who studies publishing analytics, calls “soft data”—a bouquet of assumptions about readership, authorship, markets, and genre. Those assumptions are then “turned into something that seems like it should have been arrived upon in a rigorous fashion,” she says, “but it’s not.” If enough bidders get ensorcelled by a project—or by the bloodlust of an auction—the price can be driven up into six or seven figures. The book business may be centred in New York, but the logic is pure Las Vegas.

I recommend reading it in full—there’s some fascinating commentary about how the obsession with betting on debut authors negatively affects midlist authors (who publish moderately successful but not bestseller books; Sean deLone has a thorough definition here), and how that then affects experimental, early-career writers.

The art of the impersonal essay. Zadie Smith’s latest, for the New Yorker, reflects on the essays she wrote as an adolescent—and how they shaped her approach to the form.

My entire future rested on a few essays written in the school hall under a three-hour time constraint? Really? In the nineties, this was what we called “the meritocracy.”

A comprehensive look at the literacy crisis. For anyone anxious about the potential for a post-literate society—and trying to figure out how to educate children raised on short-form video—I recommend Natalie Wexler’s carefully researched newsletter Minding the Gap on K-12 education. Most of her newsletters focus on the decline in students’ reading and writing skills, and techniques/policy interventions for improving them, but she touches on science and math education as well!

How important is scientific certainty? After reading this essay on the potential links between widespread pesticide use and Parkinson’s disease, I started thinking about how difficult it is, in practice, to “trust the science.” Some of the most important questions we ask about pharmaceuticals and chemicals—is this going to make life better or kill me?—are difficult to answer! What should governments and people do when direct causation is hard to prove, but the evidence starts adding up? As Nicholas Kristof writes,

[The pesticide] Paraquat symbolizes the challenges of environmental health and chemical regulation. Evidence accumulates, but invariably there are gaps and contradictions. Companies, following the tobacco playbook, hire lobbyists and highlight the uncertainties. And often the regulatory process drags on as companies make money and people get sick. Meanwhile, there is a growing mountain of imperfect but troubling evidence.

An incredibly charming portrait of Wittgenstein. I’ve read hundreds of essays referencing Wittgenstein-the-philosopher, but Aaron’s essay on Wittgenstein-the-man (who was also a schoolteacher, doorknob designer, and Hitler’s schoolyard bully) makes me actually want to try reading the guy. I probably won’t—because I need to get back to Schattenfroh soon—but! There’s no greater gift to intellectual culture, in my opinion, than an essay that profiles a notable figure in a fresh, appealingly personable light. Labaree does exactly that:

I really can’t express how excited I am for this autumn—for all the usual reasons (the trees changing color! getting to wear my favorite Y’s turtleneck!), but also because I’m excited to read the inaugural issues of 2 new magazines.

The first is Souvenir, a Paris-based literary and arts magazine that will be published 3 times a year. The first issue has an essay about the film industry and the atomic bomb that I’m desperate to read—and some really exceptional critical writing that Kyle Berlin sent me a preview of!

The second is Empty Set, a magazine of writing about technology that will be launching in late October in NYC. The first issue includes writers that I admire enormously, for their intellectually rigorous and original arguments about software, tech and culture. It also has an essay from yours truly, about computer art history and archiving/preservation practices. (I didn’t write any newsletters in April because all of my energy was going into this piece! And, you know, my day job as a software designer…)

Thank you for reading this newsletter. And if you’d like to leave a comment—tell me about the art you’ve seen and the stories you’re reading! And feel free to share your recent writing as well—I’d love to know what you’re thinking about.

In February, the writer and translator Federico Perelmuter wrote an entertaining, fulminating diatribe against high brodernism:

Americans can only accept foreign literature once they have washed it with superlatives…If you believe critics like me, every translated novel deserves a place among the greats or represents some feat of archival-editorial-financial gumption. To read—and announce oneself as having read—literature in translation is to be tasteful and intelligent, a latter-day cosmopolitan in an age of blighted provincialism…

Strangely, the phenomenon I reference—call it brodernism, with apologies for yet another portmanteau—doesn’t end with translated literature. It expands toward works described as “maximalist,” “difficult,” “avant-garde,” “epic,” “excessive,” “oblique,” “speculative,” “experimental,” “modernist,” “postmodernist” and “post-postmodernist.” Though men are not its only practitioners, male writers dominate the corpus, and a tendency for phallic competition underlies the formation’s core texts…

I’m no innocent: I’d argue that the publication and subsequent reviews of Mircea Cărtărescu’s imposing Solenoid, which I raved about in 2022, first coalesced (for me) this incarnation of the brodernist tendency.

I read this as Perelmuter describing a tendency in how critics write about certain books, especially translated and/or experimental and/or high modernist ones. But many people interpreted it (mostly on Twitter) as an accusation against the readers of those books. The idea being, I suppose, that the brodernist fanboy is 2025’s version of the David Foster Wallace lit bro?

What I’ve always found very funny about this is that most of the DFW fans I know are women. Anyways, I (woman) have not read Infinite Jest, though many of my friends (women) keep on telling me too…but I have read Solenoid, and written about it in 6 different newsletters (including the first one I sent, in December 2023), and convinced 3 other friends (women) to buy a copy…

It’s not included in the image above because the cover is kind of ugly. But the contents are good!

One of the best insights from Moskowitz’s How to Kill a City (2017) is that gentrification is often discussed in superficial ways—focusing on the externally visible results, not the causes. As Moskowitz writes,

For most poor New Yorkers, gentrification wasn’t about some ethereal change in neighborhood character. It was about mass evictions, about violence, about the decimation of decades-old cultures. But the reporting I’d seen on gentrification focused on the new things happening in these neighborhoods—the high-end pizza joints and coffee shops, the hipsters, the fashion trends.

The quote I keep on returning to is this:

Gentrification is the most transformative urban phenomenon of the last half century, yet we talk about it nearly always on the level of minutiae…The hipster narrative about gentrification isn’t necessarily inaccurate—young people are indeed moving to cities and opening craft breweries and wearing tight clothing—but it is misleading in its myopia. Someone who learned about gentrification solely through newspaper articles might come away believing that gentrification is just the culmination of several hundred thousand people’s individual wills to open coffee shops and cute boutiques, grow mustaches and buy records. But those are the signs of gentrification, not its causes.

Your newsletter is the one I look forward to the most, especially for book recommendations I probably wouldn't find otherwise... Immediately got Satin Island out from my library (they don't have Remainder, rip). Thank you for your work, as always!! <3

Thrilled to being having these monthly reads from you again after your hiatus! I am super intrigued by We Computers & It Lasts Forever and Then It's Over!