everything i read in july & august 2025

15 books on love, communism, AIDS activism, and sleeping your way to the top

In early July, while visiting Berlin, I found myself saying to a friend: “Culture, for me, began in 1900.” This isn’t entirely true (I love Italian Renaissance typography, for example) but I tend to gravitate to modern things. Modern art, literature, architecture, technology—and modern problems, too, in politics and society.

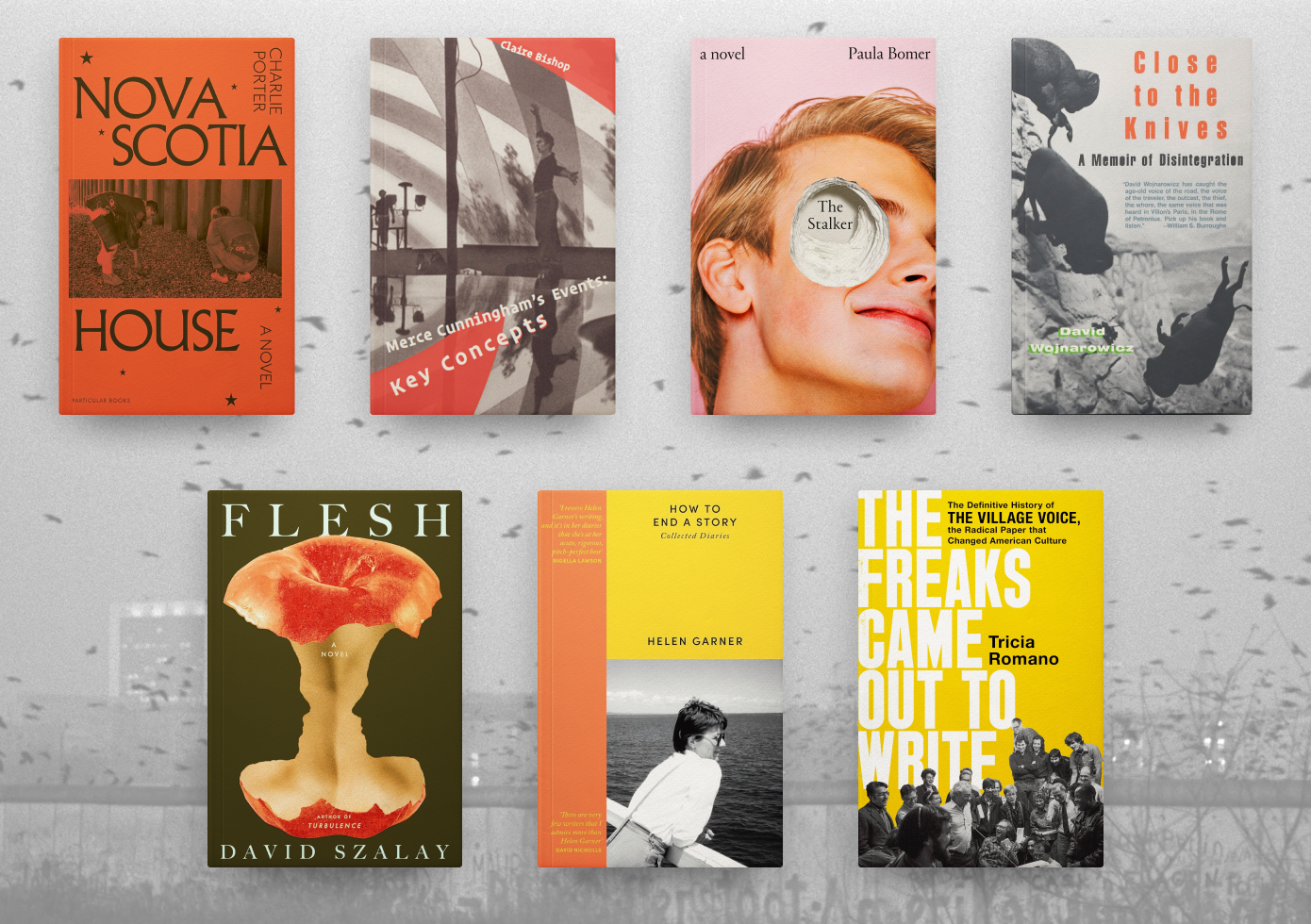

I spent most of July and August reading about the 20th century—the formation and dissolution of the Soviet Union; the AIDS crisis and activism in America—and reading a lot of contemporary fiction, some of which obliquely or explicitly dealt with these themes. Below, brief reviews and reflections on:

Books and films about twentieth-century history

Art and literature about the AIDS crisis (from Félix Gonzales-Torres to Sarah Schulman)

The state of contemporary fiction (or, more specifically: reviews of 6 novels published in the last 12 months, including 3 on the Booker longlist)

And briefer thoughts about some other books:

The renowned Australian writer Helen Garner’s diaries

A short book on dance history/choreography

A transition memoir and Jungian self-help book

Funny and charming short stories from the NYRB Classics

800 pages of peerless diary entries

The first book I finished in July was the Australian novelist and journalist Helen Garner’s How to End a Story: Collected Diaries. Garner is a household name in Australia—two friends said they’d read Garner in school—but she’s still not well-known in the US and UK, despite her Paris Review interview in 2022. But she’s an incredible writer; I can’t remember the last time I read a book with such consistently readable and beautiful style. The diaries showcase her gift for succinct, evocative character portraits (of her friends, family, strangers), and you get loose plot arcs from the dissolution of her 3 marriages (imagine having 3 ex-husbands!) and the heady ascent of her career. Three favorite quotes:

3 histories (and a film) about the twentieth century

I then spent the second week of July in Berlin, a city so irretrievably awash in history that it only felt right to read some nonfiction while I was there.

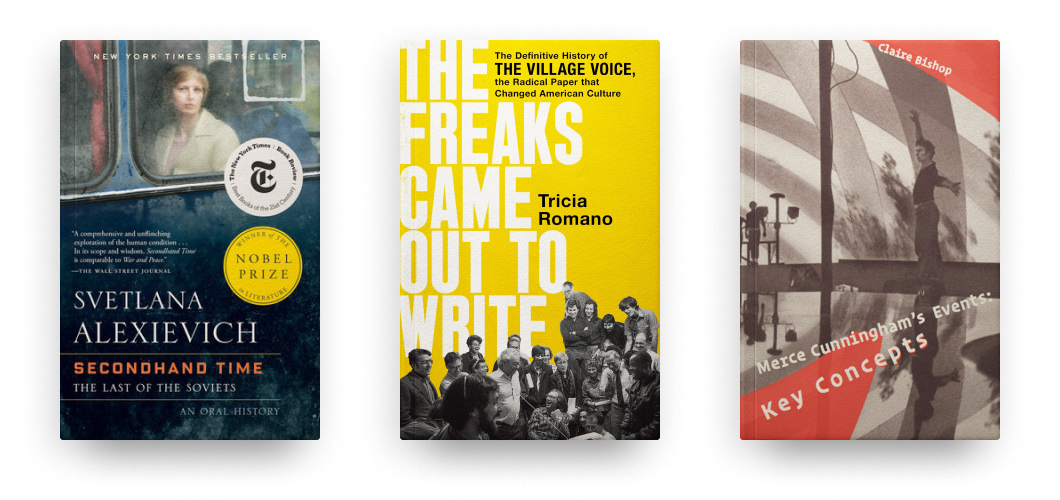

I started with Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, an oral history of the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Alexivich is a Belarusian investigative journalist and oral historian, and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2015. Her books are often described as “symphonic” or “collective” histories, because she draws together multiple interviews to describe how historical events affect people’s lives. As she said in an interview, she said:

I’ve been searching for a literary method that would allow the closest possible approximation to real life…So I immediately appropriated this genre of actual human voices and confessions, witness evidences and documents. This is how I hear and see the world—as a chorus of individual voices and a collage of everyday details.

Secondhand Time is a beautiful book and very heartbreaking. There are interviews with people who despise the Soviet days or cherish them; people reminiscing about the furtive romance of reading samizdat literature; details of what people wore and ate and sang along to. There are love stories where history intercedes: a Russian woman married to a Jewish man during WWII (she chooses to die with her husband in a mass grave, and it’s their son, who improbably escapes, who tells Alexeivich their story); a romance between an Azerbaijani man and Armenian woman, who flee their hometown after marrying due to the intracommunal violence that marked the disintegration of the USSR. I didn’t feel particularly good while reading the book; it made me feel quite low, just to read about history running roughshod over people’s lives, and all the suffering that seems inevitable to the human condition.1

I was walking through Berlin, going to museum after museum, and feeling very dispirited about all this, and then I came across a sticker:

“Oh,” my friend said, “it’s from Wings of Desire!” Which is a Wim Wenders film set in Berlin—and many of the scenes were shot, in fact, near our hotel—so we ended up watching it one evening, and I felt much more calm and peaceful again.

Wings of Desire (1987) is a very tender film about two angels looking after the inhabitants of a divided Berlin. The angels, Damiel and Cassiel, can hear people’s inner thoughts—which are often lonely, fearful, anxious—and, by placing an invisible hand on their shoulders, offer a little peace. Though the angels are eternally fascinated by humanity, and delighted by the minutiae of people’s lives, they are always at a remove. As Cassiel says, their role is to:

Keep to yourself. Let things happen. Always be serious…Do nothing more than look, gather, testify, verify, preserve.

But the other angel, Damiel, longs to be immersed in life, ordinary mortal life—and the film follows his infatuation with a beautiful trapeze artist, Marion, and his desire to abandon immortality in favor of life.

It’s funny how films can do this; they can lift you out of your loneliness and feel committed to the human condition again. Because Damiel, in the film, is so intensely curious about human life—the tastes! the colors! the sensations! the capacity to be involved, and not just observe—and I was reminded of how nice all these things are, and how they don’t seem like they should offset the usual despairs of living, but they do.

It turns out you can get a library card online and then visit the State Library near Potsdamer Platz, where many of the scenes in Wings of Desire are shot at. While taking public transit to the library, I read from Tricia Romano’s The Freaks Came Out to Write, another oral history—but this one is about the Village Voice, an influential alt-weekly founded in Greenwich Village in the 1950s. I’m writing a longer piece about this book, which will come out sometime this autumn, so I’ll be brief here! Romano’s book is a fascinating look at twentieth-century American journalism and cultural criticism, and how the Voice’s idiosyncratic writers helped shaped discourse around urban politics, the AIDS crisis, feminism, and gay rights.

And then I spent my time at the library reading from the books I bought at the Walther König bookstore near Museumsinsel. It’s such an expansive and well-stocked art bookstore, and it was incredibly difficult to leave with just 2 purchases. One of them was the art historian Claire Bishop’s Merce Cunningham’s Events: Key Concepts, which I finished in August once I was back home.

Bishop is an art historian known for her writing on relational aesthetics (which is…what? Kyle Chayka has a good explainer here) and how the attention economy has reshaped contemporary art. Her book on the avant-garde choreographer Cunningham focuses specifically on his “Events,” where Cunningham excerpted movements from his existing works to create new dances performed in non-traditional settings, from basketball courts to museums.

I wasn’t particularly interested in Cunningham before reading this book—but I knew that his romantic partner and longtime artistic collaborator was the composer John Cage, who I’m fascinated by. (And Cage is also the reason I went to the Yoko Ono exhibition at the Gropius Bau in Berlin—the two met in the 1950s and became close friends.) It’s exciting when an interest in one person/work/event leads you to another, and another, and another…

Last summer, I wrote about John Cage, Fluxus, and whether the indeterminacy of LLMs can be used in artistically innovative ways—

Bishop’s book on Merce Cunningham gave me a little more context on some key ideas in modern dance and choreography. And it was exciting to read about Cunningham’s collaborations with other people I’m familiar with, from the video artist Charles Atlas to the fashion designer Rei Kawakubo.

Art and literature on the AIDS crisis

For several years now, I’ve had 2 places bookmarked in Berlin: the Boros Collection and the Sammlung Hoffman. The Boros Collection is a contemporary art collection housed in a Nazi-era air raid shelter, which then became a techno club in the ‘90s, and then was purchased by Karen and Christian Boros to house their art collection. (The top floor is a penthouse apartment that was used as Lydia Tár’s apartment in, well, Tár.)

The Sammlung Hoffman is also a private art collection, though the building has a more modest history: it’s a former sewing-machine factory. When I booked tickets to visit, I didn’t realize that nearly every room would have a piece by the artist Félix Gonzáles-Torres.

His most famous work might be his candy piles: a cascading heap of wrapped candies, placed in a corner of a room, that viewers are invited to take. The first one, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), was created the same year that González-Torres’s longterm partner, Ross Laycock, died of AIDS-related complications. So the candy piles are often understood as making visible how someone might waste away from illness, and as a way of remembering Laycock. (Gonzáles-Torres passed away from AIDS a few years later.)

What I also learned, while visiting the Hoffman, is that Gonzáles-Torres befriended an artist named Roni Horn, after seeing her 1982 sculpture Gold Field. The two artists created several sculptures inspired by each other’s work, including Horn’s sculpture Gold Mats, Paired, for Ross and Felix.

It’s hard to describe how it felt, seeing this sculpture at the Hoffman. It was placed in a small alcove near a larger Gonzáles-Torres work, very gently lit, so that it felt like a shrine. The two sheets of gold foil immediately feel very precious, and very delicate—pressed together, with just a small, deliberate opening between them. You feel a sense of intimacy, even before you know what the title of the sculpture is and who it’s dedicated to.

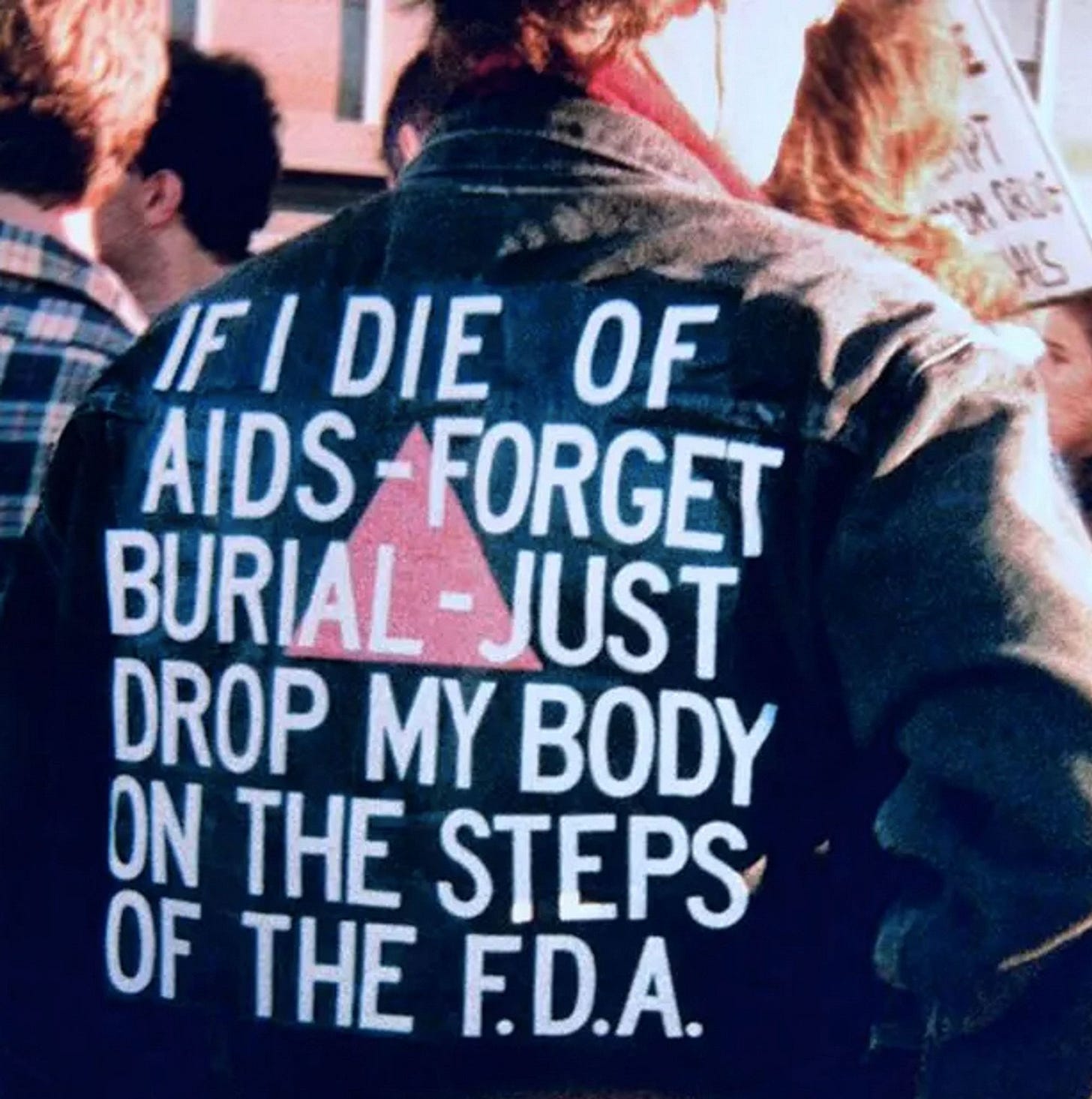

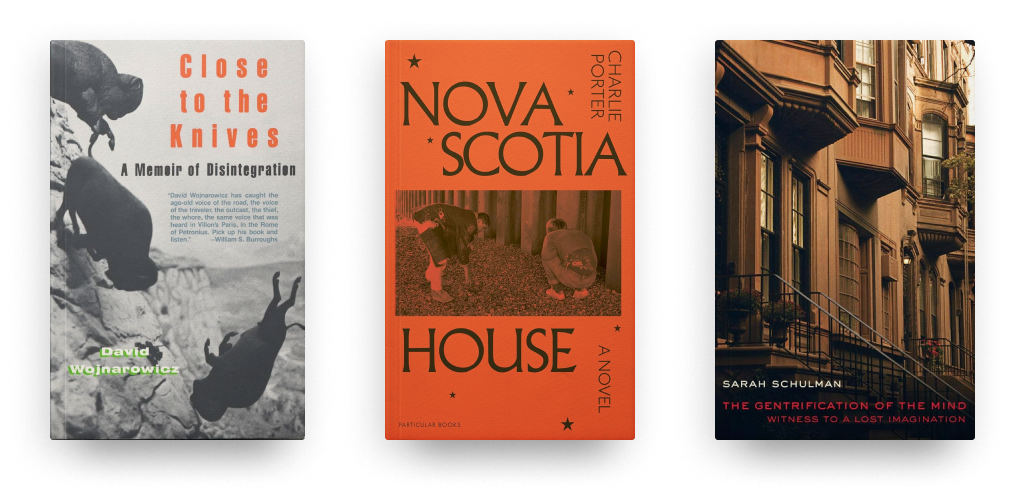

I must have been thinking of this work when I picked up the artist David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, which touches on the relationship between David Wojnarowicz and the photographer Peter Hujar. Wojnarowicz’s essay collection, which was written from the 1970s through the early ‘90s, is sharp, aggressive, touching, angry, tragic, reflective, active—often in the same essay. He conveys the seething, urgent anger of many ACT UP members in the early years of the AIDS crisis, when the CDC and numerous public officials failed to disseminate useful information about HIV, or adequately fund research into cures. Though HIV was stigmatized as a gay disease, Wojnarowicz writes about how many other communities it affected—and connects the government’s approach to other issues:

What is it about this society which supports the premature death of so many of us solely because of the fact that we are denied information about our own bodies in the time of an AIDS epidemic. Why can’t every woman who wants an abortion get one in this country? If a woman who desires an abortion has to travel miles away to get one because of restrictions imposed by the state, can we assume this woman can afford to make that trip? Why is it men who make the decisions that affect these women’s bodies? Why is it any other person but myself can make a determination that affects the health or safety of my body? Why are so many people silent in the face of this?

But Close to the Knives is worth reading for the style, too—because Wojnarowicz is so particularly good at narrating how his eyes move—

My eyes scan the surfaces of walls and tables to provide balance to the weight of words.

—and what it feels like to be alive and conscious in the world:

Sitting in the Silver Dollar restaurant earlier in the afternoon, straddling a shining stool and ordering a small cola, I dropped a black beauty and let the capsule ride the edge of my tongue for a moment, as usual, and then swallowed it. Then the sense of regret washes over me like whenever I drop something, a sudden regret at what might be the disappearance of regular perceptions: the flat drift of sensations gathered from walking and seeing and smelling and all the associations; and that strange tremor like a ticklishness that never quite reaches the point of being unbearable.

I found myself thinking about Wojnarowicz a lot while reading Charlie Porter’s Nova Scotia House, a novel set in 1980s London about a young man’s relationship with an older lover and mentor in the middle of the AIDS crisis. Charlie Porter is a fashion journalist and blogger who co-ran Chapter 10 (a queer rave in London) for over 10 years, and these experiences have clearly informed Porter’s debut novel—which includes exuberant descriptions of late nights dancing and the small idiosyncracies of how people dress.

Johnny is 19 and still in college when he meets Jerry at a nearby park, where both men have volunteered to plant flower bulbs. Jerry, who is in his 40s, introduces Johnny to his friends and world. For the next 4 years, they live together, go out together, and join groups to advocate for those living with HIV. It’s a love story, and—like just about every love story during the AIDS crisis—a painful one, but the love that Porter portrays isn’t just between the two men, but within a larger community of people caring for each other and organizing together. Larger historical events, and works, come into the story: the UK’s AIDS memorial quilt; an artwork by Félix González-Torres. It takes a while to sink into the novel’s style—Johnny is a plain-spoken and humble first-person narrator—but I ended up enjoying it immensely, because all the emotions (joy, anger, fear, solidarity, loneliness) feel direct and unmediated. It’s also a novel that ends, I think, peacefully if not perfectly happily (is it possible, ever, to be perfectly happy when you’re grieving?). After finishing it, I read an interview with Charlie Porter in WORMS, where he says:

The heart of the novel takes place from ‘91 to ‘95. I wanted to look at this period because a lot of AIDS narratives, in terms of fiction and plays, are usually about the beginning of the crisis…I really wanted to look at a period of urgency, but also resignation, desperation, exhaustion. It was a different period, culturally—everything had changed.

Urgency is central to the book. Jerry has to try and tell Johnny as much as he can about life before the AIDS crisis, which is the point of the book: trying to reconnect with experimental living and queer philosophies from before…And then the urgency in the present day is Johnny trying to work out his life, not to stagnate but to actually try and regain that urgency—urgency in anger. [Wojnarowicz’s memoir] Close to Knives is a very angry book, quite rightly.

To close off this theme, I also read the writer and activist Sarah Schulman’s The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination. It’s a beautiful memoir of the AIDS crisis: the people Schulman befriended and loved and lost; the passionate intensity of ACT UP, the direct action group that pushed for significant investments in research and access to treatment; and the reason that Schulman cofounded the ACT UP Oral History Project (with Jim Hubbard) to commemorate the group.

“The AIDS experience,” Schulman writes, was where she came to understand that:

It is a fundamental of individual integrity to intervene to stop another person from being victimized, even if to do so is uncomfortable or frightening. That the fear and discomfort must be separated from the decision to act…

Every historical moment passes…McCarthyism passed, even the Holocaust passed. Outliving the historical moment with your integrity intact is a risky business. I’m glad I witnessed the beauty of ACT UP so that I know it is right and possible to intervene on behalf of others, thereby repositioning one’s self towards the acknowledgment that other people are real, even if they have less status and are more endangered.

Reading Schulman’s writing is always invigorating and always a challenge—intellectually and morally. She reminds us that our future selves will be asked to answer for whatever we’re doing now—and whether we have acted with “intellectual integrity and integrity of action.”

The state of the contemporary novel

For the second half of August, I read a lot of contemporary fiction. Why? Because I am always seeing people complain about how there are no good novels, and contemporary literature is dead—killed off by the MFA industrial complex, identity politics, the consolidation of the publishing industry, or something else.

But I’m someone who wants direct evidence! I want to know what contemporary literature people are reading, and exactly what conclusions they’re drawing from it! So that’s why I read 6 novels from the last 12 months:

3 of them were longlisted for this year’s Booker Prize:

David Szalay’s Flesh, which I bought after Henry Oliver’s effusive praise. This novel is phenomenal; completely, skillfully executed on a technical level (perfect pacing, perfect prose) and a very compelling story that sticks with you long after you finish reading. It’s also the kind of novel you’ll finish in one sitting and be upset if anyone tries to interrupt you! Briefly: it’s a propulsive rags-to-riches story of a young man, István, who gets caught up in other people’s plans—sometimes altruistic, sometimes sexual—and dragged through different social and economic classes in Hungary and London. It’s an incredibly eventful story, but narrated with a cool restraint—István’s interiority is very subtly done. Almost certainly one of the best novels published this year.

Ledia Xhoga’s Misinterpretation, a novel about an Albanian interpreter whose impulsive do-gooder instinct puts her marriage and well-being at risk. It’s like a thriller version of Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies. As I wrote in my Goodreads review, you wouldn’t expect a novel about immigration/trauma/the ethics of interpretation/being married to a arthouse film professor to have so much suspense…but it does! It’s a very impressively executed novel, and the main theme of the novel—how much should you go out of your way to help others? and can you ever save someone else from their problems?—is very movingly explored. My friend Megan Marz also wrote an excellent and insightful review of Misinterpretation in the TLS.

Natasha Brown’s Universality. I wanted to like this much more than I did—especially since I loved Brown’s first novel, Assembly. Structurally, this novel is very promising: it opens with a fictional article about a wealthy financier cheating on his wife, a bombastic anti-woke newspaper columnist, and a wayward son who’s joined an anarchist commune. Then the novel shifts between a few different perspectives—starting with the journalist who wrote the article, and ending with the anti-woke columnist she profiles—revealing how the article changed everyone’s lives. Universality is an astute commentary on several contemporary issues, including the precarity of freelance journalism, and how class anxieties in the UK have increasingly centered around anti-migrant rhetoric. It’s also a funny depiction of how writers can strategically use debates around immigration, DEI and class inequality to advance their careers. My problem with the novel is that it feels too literal and unsubtle. I’m reminded of something Ottessa Moshfegh said in 2021:

I wish that future novelists would reject the pressure to write for the betterment of society. Art is not media. A novel is not an “afternoon special” or fodder for the Twittersphere or material for journalists to make neat generalizations about culture…We need novels that live in an amoral universe, past the political agenda described on social media.

The novel’s characters all feel drawn from the news. Everyone is a Type of Guy that I’m already familiar with and already dislike, but because they’re rendered so obviously and flatly, I often felt condescended to as a reader. Brown does attempt to make the characters a bit more dimensional—no one is obviously evil or obviously good—but it’s not quite enough.2

I read 3 other novels from 2025—I’ve already mentioned Charlie Porter’s Nova Scotia House, but there was also:

Paula Bomer’s The Stalker, which my friend Klara recommended. We both feel personally injured and outraged that this novel has not been discussed, reviewed, and praised more—it’s astonishingly well-written and one of the most hilarious/disturbing/charming/unsettling narrators I’ve come across lately. It follows an obnoxiously self-assured young man as he attempts to make it in NYC…by manipulating and coercing women into providing him with free drinks, unfettered access to their apartments, money, drugs and sex. The novel is written with such joie de vivre and exuberance—it feels like an endless, picaresque caper to see how much he can extract from other people—even as the man’s exploits become more, well, exploitative. Also a book you’ll knock out in one sitting—it’s very fast-paced.

Sophie Kemp’s Paradise Logic, an unhinged (complimentary) and distinctively written novel about being obsessed with love and disappointed in its pursuit. It follows a young, mostly broke, vaguely employed 23-year-old woman trying to find a boyfriend in NYC—with occasional mythic interludes narrated by a voluble omniscent narrator. Kemp’s prose style is polarizing, but I’m a fan—I wrote in my Goodreads review that Kemp “has a real talent for writing a nearly-intolerably-terminally-online interior monologue that is actually expertly pitched…the internet-y voice doesn’t distance you from the story in a posture of irony, but rather makes everything more intensely felt.” Paradise Logic has the psychosexual intensity and earnestness of Sheila Heti’s Pure Color, but refracted through a million memes.

Finding meaning and finding yourself

I’ll close this newsletter out with 3 final books: a self-help book, a memoir, and a short story collection.

I read the Jungian psychoanalyst James Hollis’s Finding Meaning in the Second Half of Life, which is essentially a self-help book—but long-time readers know that I’m addicted to self-help and find it very encouraging in times of crisis and calm. Hollis is interested in the process of individuation: how to consciously choose the life you want to live, and the values you want to uphold, instead of automatically absorbing familial and social expectations. The book is quite insightful when it comes to the mistakes we repeatedly make (and what unconscious tendencies lie behind them); when people over-rely on love; and what to do when you feel “intimidated by the task of life.”

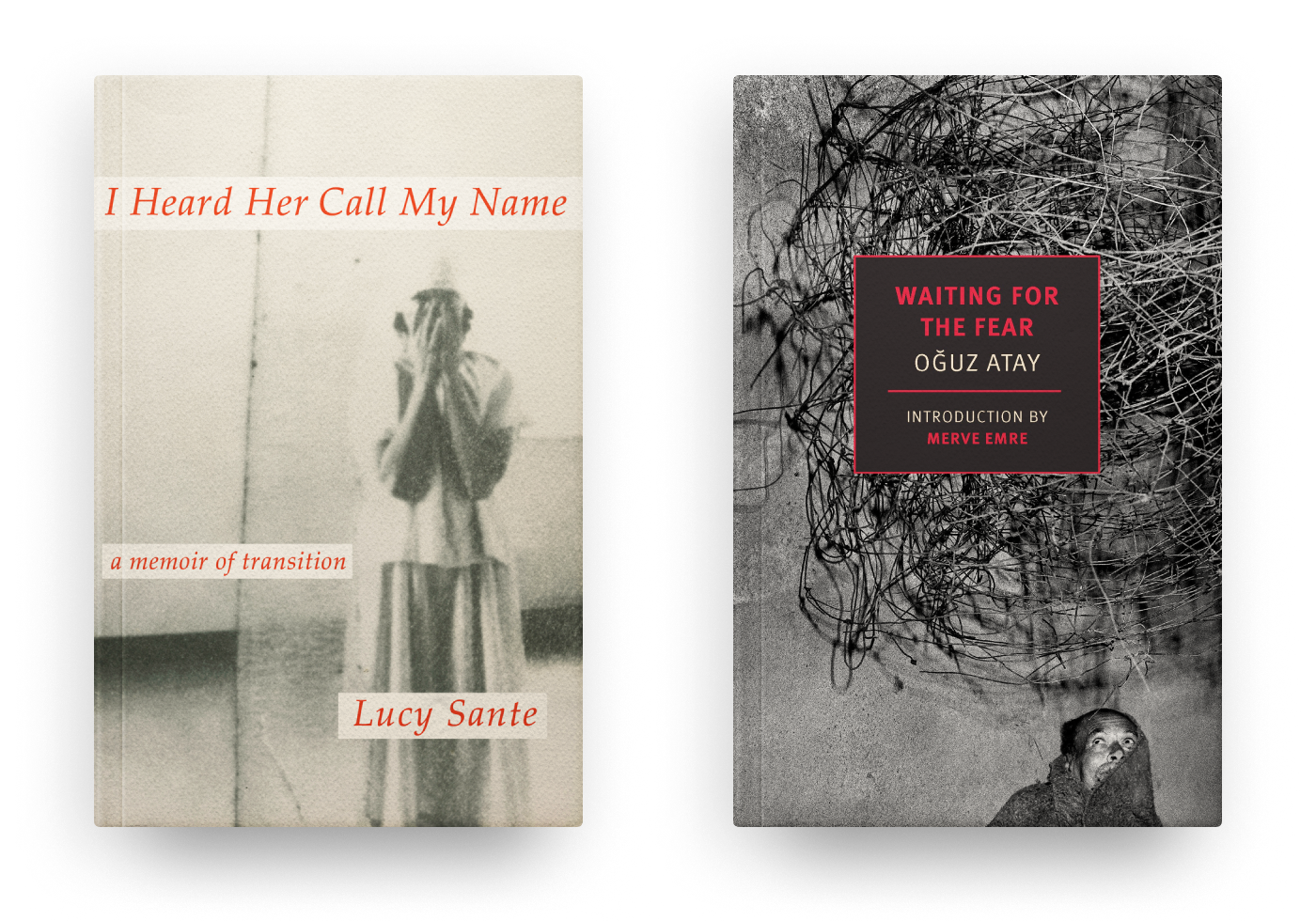

I also read the critic and artist Lucy Sante’s I Heard Her Call My Name. It’s a memoir that loosely traverses Sante’s early childhood, adulthood, and middle age—and describes how, in her 60s, she realized she was trans. Sante is an introspective, deliberate, sensitive writer, and the memoir is her attempt to understand why it took so long for her to realize who she was. She returns to her past writing, including a prose poem she wrote in 1978, at the age of 24, which was set to music and then used for a Wim Wenders film, The State of Things. The song includes the lyrics:

It was the beginning of a new dream which was real life, or the manifestation of an old one at its cusp. She imagined they took her in a white car to a room in a club…The other women looked back at her, but they were sisters under the mink.

As Sante observes in her memoir:

My subconscious was attuned to my being and my desires in a way that my conscious mind couldn’t afford. The sophistication of my repressive mechanism can be gauged by the fact that I was able to write those words, show them to my friends, hear them set to music…print them in a chapbook…and not once tumble to their real subject, which seems unmistakable to me now. For that matter, look at the refrain of the other song I wrote for the Del-Byzanteens…“If I only have one life, let me live it as a lie”…The conflict is spelled out so explicitly you’d think I would have noticed.

Lastly, I read Oğuz Atay’s Waiting for the Fear, translated from Turkish by Ralph Hubbell. I received this from the NYRB Classics Book Club subscription last November, but have been very behind on reading it! (But that was also the month I started a new job and moved from San Francisco to London.) It’s just great—so playful and charming, if you find interminable interior narrative and profound, restless anxiety charming in literature. For example—in the title story, “Waiting for the Fear,” a man returns home, preoccupied with his thoughts, and casts his eye around the hallway:

I walked with my thoughts up my street of three houses, and suddenly I found myself standing at my door. Which means I’ve been thinking, I said. Because that’s what always happened when I thought. Before I’d have a chance to get my keys ready, my door would suddenly appear. Then, on my way to my rocking chair in the sitting room, I come up with other things to think about: how I need to unlock the deadbolt, turn the key in the main lock twice, take the room keys from the vase…When you’re afraid to be alone, the loneliness gets worse…Not all was lost, while there’s life there’s hope, barking dogs don’t bite. Ah, God damn it all!

Then I looked away from the vase at the other objects in the hall; which meant I was done thinking. (One should consistently refer to certain unchanging measures to remember that one is alive.) That’s when I suddenly saw the envelope. There among the hallway’s familiar objects, it stood out as the only foreign thing…

Thank you, as always, for reading! I’d love to hear about the contemporary novels you loved or hated; the memoirs that have stayed with you; and any art/films/exhibitions from the summer. Have a beautiful September.

It’s easier to read about historical cruelties when they feel, well, part of the past. But all the triumphant narratives about “the end of history” that came after the fall of the Soviet Union, which seemed to affirm the supremacy of Western liberal democracy, all feel very hollow now—especially when you look at American politics. There’s a new headline every week (sometimes every day) about the Trump administration’s hostility towards public servants at the CDC and EPA (the one I woke up to yesterday, was about stripping union protections from thousands of federal employees).

History isn’t over; we’re living in it, and eventually there will be books written about this time. And the writers and readers will try to understand why things could be so bad, for so long, and no one seemed to be doing anything, or people weren’t doing enough, or all the things people were doing weren’t working…

Here’s what I mean by the obviousness of the characters in Universality—you have characters like John, whose internal monologue is:

Little wonder, John mused, that the public had such a mean understanding of the topic…He was glad he’d found other, better, sources of information. The books, blogs, and podcasts that would follow the science wherever it led, even if—fuck it, especially if—the end result wasn’t woke. A fear of facts was holding the country back. He looked into Hannah’s dull, unthinking face, the inadvertent herald of Western society’s decline, stupidly chewing an olive.

And his wife will chastise him by saying:

“Oh, stop pretending it’s all so deep,” Guin sighed. “You read a Harry Potter fan fiction when you were a student and it derailed your entire life. It’s possible to appreciate statistics without making it your whole identity.” She turned to Martin and Hannah. “Did you know, I had to talk him out of getting a Bayes’ theorem tattoo.” “In the time of Love Island and identity politics, I’d say that appreciating the scientific method is a valid point of differentiation,” John said with dignity.

It’s not subtly described at all.

I am so glad to hear you enjoyed Nova Scotia House. It took me a little while to get into it too but I found it absolutely unforgettable. In addition to the love story, what has stayed with me is the idea of creating physical spaces inspired by pre-AIDS epidemic queer culture and community.

Re: recommendations, I just finished Sad Tiger by Neige Sinno. Very Ernaux-esque but absolutely gorgeous on its own merit. I think you would appreciate it. Also, of course, super excited for the new Ernaux later this month.

So many well-done reviews of so many intriguing books! Hard to decide what to add to the TBR list. Wonderful quandary. I enjoy old classics and new fiction and everything in between. I’m with you—the are of tons of great newish novels. What I’ve figured out from you and other Substack reviewers/book-lovers is that most of them are never reviewed in big media book reviews.