everything i read in january 2026

what Substack can learn from James Joyce ✦ philosophy from Bergson to Zhuangzi ✦ and essays/paintings worthy of sustained attention

Novels can be ethical projects, but I usually don’t read them for that reason. I read them to escape reality (or believe in a better one), and I read them for their beauty.

Nonfiction, however, is for understanding, explicit learning, doing. January is, conventionally, the month for reevaluating one’s life and inaugurating new behaviors; it’s also been, especially in the last 2 weeks, a month of disorienting political events. Because of that, I ended up reading very little fiction, and a lot more nonfiction and philosophy. It’s hard to escape the world right now; I’m also not sure I want to.

In this newsletter:

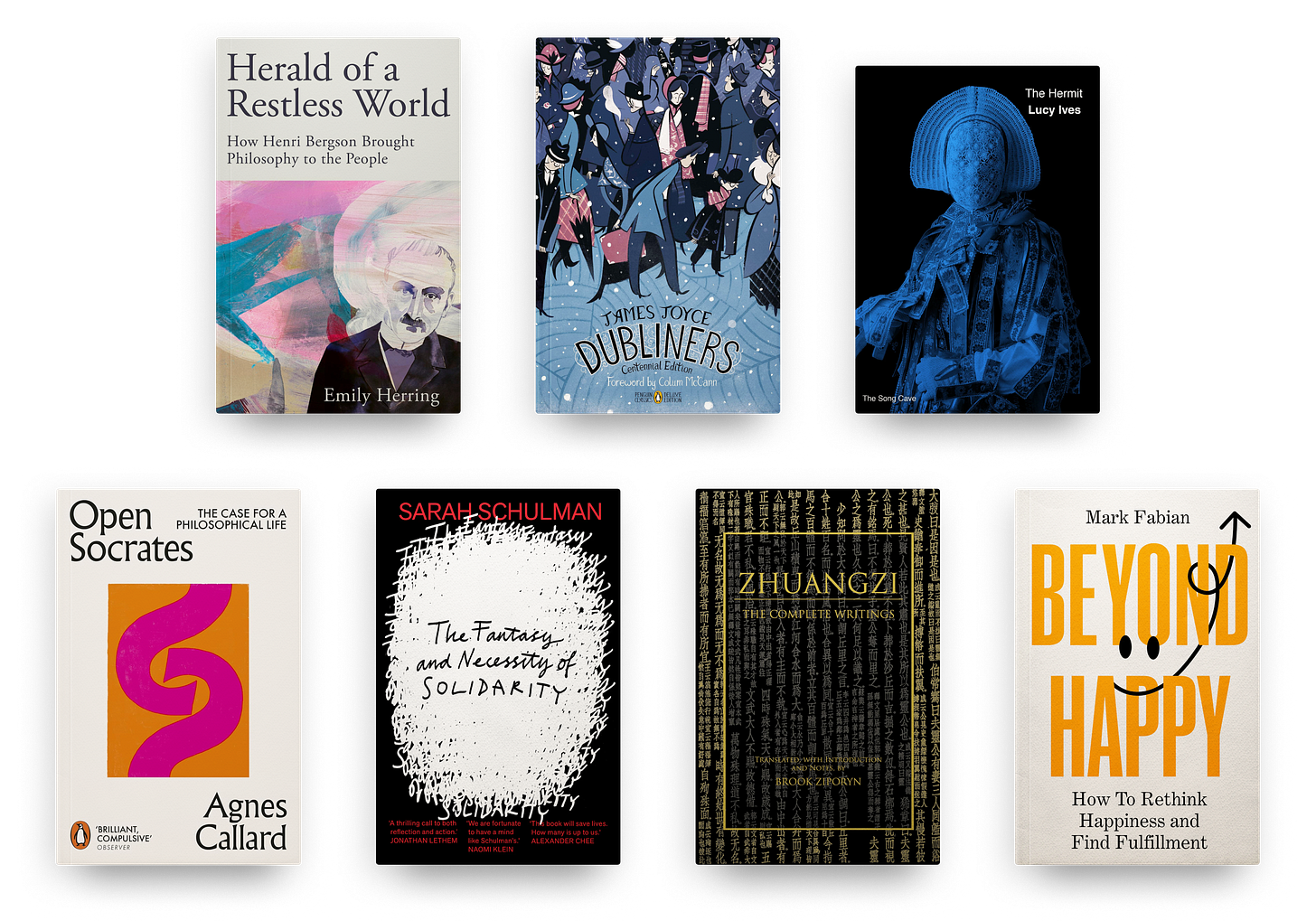

7 books—including James Joyce’s Dubliners; a very rereadable poetry book; philosophy books about Henri Bergson, Socrates, and Daoism; Sarah Schulman’s advice for political activists; and an econ/policy prof’s advice on living well

10 essays—published in Liberties, the New York Review of Books, and the newsletters of 2 great novelist-critic-thinkers

2 contemporary American painters

Fiction

I celebrated Christmas and New Year’s in HCMC/Saigon, and upon my return to London, immediately got sick. I spent two days in bed, feeling sorry for myself and scrolling pitifully on my phone. On the third day, I decided to read James Joyce’s Dubliners.

Dubliners is Joyce’s first book and his ‘purest,’ according to Edna O’Brien. In the introduction to my copy, O’Brien describes the nine years that Joyce spent trying to find a publisher. Many thought that the stories were too lewd, but by 21st century standards, what comes across is a touching, unflinching awareness of how love and desire shape people’s lives.

The first 3 stories are written in the first person—the perspective that, in my opinion, is easiest for 21st century readers to sink into. The internet is where most of us do our reading, and the internet is dominated by first-person tweets, Tiktoks, Instagram captions, and essays. I, I, I, I—the pronoun that appeals to me faster, draws me in quicker, than a story that begins with She called, He began—until I’m invested in the story, and then I’m interested in any perspective the writer pulls me into.

For more amateur theorizing on short fiction for internet attention spans—

What are Joyce’s stories about? Two young boys that escape school for the day, and end up nervously dodging an older man who’s taken an interest in them (‘An Encounter’). A young woman sleeps with a man staying at her mother’s boarding house, and all 3 of them are quietly terrified by what must happen next—what the women must demand of the man, what honor urges him to do, what resistance his family might have towards their partnership (‘The Boarding House’). A man experiences, for a time, deep companionship and affection from a married woman, before his rigidity ends their friendship and consigns them both to loneliness (‘A Painful Case’).

I was astonished, as I wrote in my Goodreads review, by how readable the stories were, and how unobtrusively beautiful the language was. ‘Araby,’ one of the early first-person ones, has this beautiful description of the rain:

Through one of the broken panes I heard the rain impinge upon the earth, the fine incessant needles of water playing in the sodden beds.

And the psychological and social world of the stories is no less vivid. ‘All the characters,’ Edna St. Brian observes,

are on the verge of something, on the verge of death, disgrace, leaving home, relinquishing love, or finding out the truth…The stories are also full of humour, crammed with the small miraculous absurdities of everyday life. Joyce wrote with the eye of a child and an adult, the perfect, indeed the only fusion, for any writer.

[The stories] steal into one’s consciousness, so the stories are lived by us and the moments from them become part of our own experience…A great writer’s first work is often his purest, and this is certainly true of Dubliners. The man who conceived them had no thought but to depict the pain and longing of people like himself whose dreams outdistance their chances.

Nonfiction

How to change the world

In her nonfiction work, Sarah Schulman—writer, activist, historian—specializes in taking overused words (abuse, activism, solidarity) and turning them back into useful political instruments. Her 2016 book, Conflict is Not Abuse, shaped many of my beliefs on how to engage in political discourse and disagreement; her next nonfiction book, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York (2021), shows how the idea of ‘activism’ was laboriously, lovingly implemented in ACT UP’s response to the AIDS crisis.

Schulman’s newest book, The Fantasy and Necessity of Solidarity, is something of a handbook for people who want a more useful definition of ‘solidarity’—and what it means, practically speaking, to act in solidarity with the oppressed. The book, which was published in April 2025, is largely focused on recent Palestinian/anti-Zionist political organizing in the US. But it also draws from Schulman’s decades-long involvement with the Boycott, Divest, Sanctions (BDS) movement, and the lessons she’s learned from her involvement in ACT UP and, before that, in abortion activism.

Schulman takes activism, she acknowledges that the right tactics aren’t always obvious. A key problem, for her, is that activists can be impatient; as she compassionately explains,

it is very easy to want change immediately and get angry or accusatory—to condemn each other, to create hierarchies of radicalness or other forms of blame—when change doesn’t go your way. We feel so terrible when we realize, and we want to feel better. But creating change…is probably the most difficult obstacle many of these important and needed new activists have ever faced.

Activists, Schulman reminds us, ‘have to be committed to problem-solving,’ and understand that their responsibility is to be effective, not merely to be outraged. In chapter 5, ‘The Case for Strategic Radicalism,’ she offers a detailed discussion of the tactics the BDS movement has found most effective over the years, especially context sensitivity and creativity. When it comes to university movements to divest from Israel, for example, she notes:

What is possible on one campus may not be possible on another. As such, we should recognize that power comes from a diversity of tactics that keep the overall goal in mind…

“Factionalizing”—claiming that your strategy toward the common goal is better than someone else’s—is the downfall of movements that depend;…on many different approaches, tactics, and actions all aimed at the same goal.

One of the things that made ACT UP so effective during the AIDS crisis, she notes, is that the movement did not require consensus. Activists could, and often did, pursue strategies that others didn’t agree with—as long as they fulfilled the basic requirement of ‘direct action to end the AIDS crisis,’ people could proceed. The result, Schulman writes, is that ‘there was a broad range of many different kinds of actions with different methods and aesthetics, aimed at different social milieus, that would take place at the same time.’

What Schulman is describing reminds me of the tactics Charles Duhigg recently described in a New Yorker article, ‘What MAGA Can Teach Democrats About Organizing.’ What made Obama’s presidential campaign so effective, Duhigg argues, is the autonomy that volunteers were given. In 2009, a Republican operative copied this model to slowly assemble an influential, nation-wide coalition, where local chapters were encouraged to come up with their own strategies—unlike some of the most influential Democratic advocacy orgs.

Philosophy, from ancient China to twentieth-century France

In early December, I came across Minh Tran’s very funny newsletter, ‘My Year of Rest and Chinesemaxxing,’ which functions both as trend commentary and nonchalant geopolitical analysis:

The most fashionable thing you can do in downtown New York these days is drink a beer on Canal Street, crouched on a low plastic stool in vintage Margiela…

In the twilight of the American empire, our Orientalism is not a patronizing one, but an aspirational one.

Perhaps it was Tran’s newsletter, or afra’s essay on the Chinese tech canon for Asterisk Magazine—that made me feel a strong desire to differentiate myself from more shallow forms of Chinesemaxxing. And then, for my birthday, I received a copy of the Chinese philosophy classic, Zhuangzi (translated by Brook Ziporyn) from my friend Jules.

So my year of Chinesemaxxing began with me working through the 33 chapters of the Zhuangzi, written (likely by multiple authors) around 575–221 BCE. The book is a foundational Daoist text, along with the more famous Daodejing, and Ziporyn’s translation brims over with cheerful, playful, and evocatively poetic lines. As a lover of translated literature, I found Ziporyn’s notes on the translation almost as fun as the actual text.1 Which is saying something, because the Zhuangzi is full of funny little fables!

One of the most famous passages appears on page 21:

Once Zhuang Zhou [the supposed writer of Zhuangzi] dreamt he was a butterfly, fluttering about joyfully just as a butterfly would. He followed his whims exactly as he liked and knew nothing about Zhuang Zhou. Suddenly he awoke and there he was, the startled Zhuang Zhou in the flesh. He did not know if Zhou had been dreaming he was a butterfly, or if a butterfly was now dreaming it was Zhou. Now surely Zhou and a butterfly count as two distinct identities, as two quite different beings! And just this is what is meant when we speak of transformation of any one being into another—of the transformation of all things.

The butterfly is to Zhuangzi what the madeline is to Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (or linen is to Marx’s Capital); it’s the reference everyone is eager to make, to signal that they are in the know…but it actually appears quite early on!

If you want to be that guy or girl at the party, obnoxiously perseverating on your superior knowledge of Zhuangzi, my recommendation is to instead reference the worthless tree, a character that appears in chapter 4 and again in chapter 20.

The worthless tree is enormous: ‘over a hundred arm spans around, so large that thousands of oxen could shade themselves beneath it…[and] surrounded by marveling sightseers.’ In chapter 4, a carpenter and his apprentice walk by, and the apprentice timidly asks why the carpenter doesn’t want to chop it down. The answer?

This is worthless lumber! As a ship it would soon sink…as a tool it would soon break, as a door it would leak sap…This is a talentless, worthless tree. it is precisely because it is so useless that it has lived so long…

The tree considers it a great disgrace to be surrounded by this uncomprehending crowd [of admirers]…What it protects, what protects it, is not this crowd, but something totally different. To praise it for fulfilling its responsibility in the role it happens to play—that would really be missing the point!

This passage showcases some of the playful storytelling in Zhuangzi, along with the strange, enigmatic lessons about the intrinsic nature of different beings. The book is constantly returning to the concept of one’s ‘intrinsic virtuosities,’ and how people ought to accept their inner natures, and the inevitable transformations of the world, and…this is my interpretation, at least…not force things? Not exert oneself needlessly, but rather be open to ‘non-doing,’ to patient observation and the passage of time?

It’s difficult for me to summarize this book (and there have been, quite literally, over 2000 years of scholarship into Zhuangzi). But it’s a supremely delightful and funny read, even though I find its ideas very mysterious:

I also read Emily Herring’s Herald of a Restless World: How Henri Bergson Brought Philosophy to the People, which I found out about through Substack! Bergson is, today, one of the lesser-known names of 20th-century French philosophy, but he was an international celebrity in his day—filling lecture halls, causing traffic jams, and relentlessly pursued (and, sometimes, envied) by other aspiring intellectuals:

Bergson, who won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1927, wrote beautifully about the role that intuition could play in a scientifically-oriented society. And he was well-known—like his second cousin by marriage, Marcel Proust—for his writings on time, memory, and consciousness.

In 1904, Bergson wrote to Proust: “I believe, as you do, that every form of art sets out to convey certain states of mind that would be inexpressible in any other language: that is the raison d’être of that art.”

Today, Proust is a household name, while many people are unfamiliar with Bergson. But for much of their lives, the situation was quite different:

While Bergson had reached almost unfathomable levels of notoriety, Proust was still making his way towards literary icon status. In the final months of 1913…[Proust] had just suffered the sting of several rejections and had to resort to self-publishing the first volume of one of the twentieth century’s most imposing literary monuments, In Search of Lost Time.

How to understand your values

January is a good month for finishing up loose ends from the last year—which, for me, meant finishing my copy of Agnes Callard’s Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life. Last March, while I was—going through it, to put things obliquely—my friend Rachdele let me cry profusely over lunch at Bon Nene (in San Francisco’s Mission District) and then gently led me over to Dog Eared Books on Valencia Street, where she bought me a copy of Callard’s book. For the rest of the year, I treated it as something of a protective talisman—a reminder that I had beautiful and warm friends around me, and I would eventually stop crashing out and be okay.

Callard is something of a cheerfully confronting philosopher—the first paragraphs of Open Socrates are:

There’s a question you are avoiding. Even now, as you read this sentence, you’re avoiding it. You tell yourself you don’t have time at the moment; you’re focused on making it through the next fifteen minutes. There is a lot to get done in a day. There are the hours you spend at your job, the chores to take care of at home.There are movies to be seen, books to be read, music to be listened to, friendships to catch up on, vacations to be taken. Your life is full.It has no space for the question, “Why am I doing any of this?”

True, you might sometimes have to pause to ask: Should I take a vacation? Move? Have a(nother) child? Or you might find yourself faced with a moral dilemma or a romantic crisis. But in those cases you frame “What should I do?” as a question about which option fits best with what you had antecedently determined that you have to do and like to do. You are careful to keep your practical questions from exploding beyond narrow deliberative limits within which you confine them in advance. It is fine to be open-minded and curious about all sorts of questions that don’t directly impinge on how you live your life—How do woodpeckers avoid getting concussions?—but you are vigilant in policing the boundaries of practical inquiry. You make sure your thinking about how your life should go doesn’t wander too far from how it is already going.

You appear to be afraid of something.

If you, like me, find yourself irresistibly compelled by this passage—nervous but eager to bring that question into conscious awareness, and attempt to answer it—you might enjoy this book. It is, essentially, an introduction to the Socratic method, and a love letter to philosophical inquiry. I read most of it last summer, then put it down for several months, and only finished it up in January—but I’m realizing, now, that it must have exerted a strong influence on me, because I’ve been reading a great deal of philosophy since last March.

After that, I picked up what I like to think of as applied philosophy: a self-help book. Longtime readers will know of my eternally embarrassing addiction to this genre. Most self-help books are bad, I’ll admit. But a handful of them are exceptional, and Mark Fabian’s Beyond Happy: How to Rethink Happiness and Find Fulfillment is in the latter category.

Fabian is a public policy professor in the UK, and previously worked at the Brookings Institution and did his PhD in economics. Much of his research is focused on human wellbeing, and how public policy can contribute to that. His overall goal is ‘to update welfare state theory for the 21st century…taking 'welfare' beyond material considerations into the psychological and sociological domain.’

Beyond Happy takes Fabian’s research and makes it more accessible and practically useful. It is centrally concerned with how we find meaning and purpose in our lives—it acknowledges, but doesn’t focus on, the typical concerns of the self-help genre. There are lots of good books about habit formation (James Clear’s Atomic Habits) and time management (Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks); Fabian’s book differentiates itself by trying to understand questions like:

What do we lose when we’re not religious, since religion has historically offered meaning and clarity in our lives?

How do we combat nihilism, when it seems like there’s no objective, intrinsic value to cling onto?

How do we know who we are? How do we know our values?

Fabian persuasively argues that we can’t solve a crisis of meaningless by retreating into the past. Old religions and traditions won’t cut it; we need to integrate the lessons of the past, and consciously carve out a new approach to life. He also argues that one of the foundational aspects of our well-being is a sense of community involvement and social responsibility—we can’t be truly well unless we are part of other people’s lives, and contributing to their well-being.

How to confront political reality

A week or two after I finished Fabian’s book, Renée Nicole Good and Alex Pretti were killed in Minneapolis. Their deaths show how futile it is to secure individual wellbeing in a state of community crisis; and the response to their deaths, I think, shows how wellbeing can actually be enacted—through mutual care, ordinary activism, and intransigent solidarity.

It’s moving to read articles like Adam Serwer’s profile of ICE protestors and community volunteers in The Atlantic, where he notes:

The number of Minnesotans resisting the federal occupation is so large that relatively few could be characterized as career activists. They are ordinary Americans—people with jobs, moms and dads, friends and neighbors.

—or Emily Witt’s article about how teachers and families are coming together to keep their community safe, in the New Yorker:

As of late January, around forty per cent of the elementary school’s students have been staying home, and many of their families no longer leave the house.…

The school began formulating its response to the crisis in December. Meetings were held to figure out how best to assist the families. Laptops and mobile hot spots were distributed…A GoFundMe was initiated to cover rent and groceries for families who have stopped going to work; parents and other volunteers are connecting detained parents with legal assistance…

Distance learning is scheduled to end, but the school staff expects that it will be extended. The adults have tried to explain the situation to the children the best they can. The principal said that teachers have incorporated lessons about boycotts and protest. “So they can kind of connect it to that,” the principal said. “The kids know that there’s a way to respond when you feel like something is unjust.”

Other work that helped me process what’s happening in in the US:

Sarah Thankam Mathews on grief as an emotion and a political capacity:

Where I come from, mourning is not something you feel. It is something you do. Mourning can be…a precondition to other political acts.

Grace Byron on political personality cults and choosing coalition-building instead:

[Trump] is the final boss of personality politics, someone so invested in his legacy and mythology that he has eaten through the guardrails of an already fragile democracy…Liberalism too is at a crossroads. Many are tired of the same old answers…they want a new coalition, one where their neighbors are not subject to public execution.

Poetry

I’ve been carving out one day each weekend to sit at home and write, preferably with a friend. A few weeks ago, my companion du jour was working on some poems—so I pulled some of my poetry books out, including the poet-critic-professor Lucy Ives’s The Hermit.

I loved rereading this (I last wrote about it in October 2024). There’s really no one like Ives—her writing is deeply immersed in French theory and American history and literary studies, but it never feels weighed down. The 80 poem-shaped fragments in this book are so legible! They’re airy and easy to read, easy to assimilate—even though they touch on all these grand, abstruse academic topics:

If you’re a fan of Lydia Davis, this collection offers similar pleasures. Here’s poem #8 in The Hermit, which has that inwardly-observing-thinking-about-thinking quality that so many of Davis’s stories have:

A man, still young at this point in the story, considers how he senses desire in others. He has thought of it as his own possession, their desire, and this has led him to behave stupidly. One is implicated but not automatically, not without one’s own permission, for there is no good in love. One loves actively, on principle—or one attempts, erroneously, to possess desire, as he has done. And yet, the young man thinks, it is no better not to love. It seems like truth to him; it takes the form of a command. He grows old. He is old. He is old and alone, but still thinking. He wants to know what would constitute a true command. Is love a command? The man may even be dying now, is about to die, is dying, when he begins to ask himself, Is it not my own permission that lends love this form?

Magazines

I’m the living embodiment of that eternal @dril tweet, except my problem isn’t candles but magazine subscriptions.2 The issue isn’t the money spent; it’s that they tend to go unread. But one of my 2026 resolutions—alongside the usual ones, like Go to the gym regularly—is actually reading all the issues that arrive on my doorstep! In January, that meant:

Liberties (the winter 2026 issue) ✦

Liberties is a magazine of culture and politics founded in Washington, D.C, and an annual subscription is $50 (with discounts for students and educators). Two of my favorite articles from this issue were the philosopher Agnes Callard’s ‘In Search of the Leisure Class,’ and the editor Celeste Marcus’s ‘“I Am Trying to Live a Life I Do Not Understand”.’

Callard’s ‘In Search of the Leisure Class’ is typical of Callard’s writing—keenly inquisitive, conversational, and funny. The essay asks what leisure could be—that thing that isn’t work, isn’t rest, but is some secret third thing. As Callard writes,

When someone doesn’t want to do just any job in order to survive but insists on finding what she will consider “meaningful work,” she is saying that she wants her work to be (at least somewhat) leisurely; likewise, when someone resists “guilty pleasures” of entertainment in order to engage with something she finds challenging, she is demanding leisure in her rest time.

Leisure is, for Callard, one of the most important human pursuits. And yet:

We are living in unleisurely times. The internet and phones and social media offer up many insistent work-like demands on our attention, many rest-like temptations for entertainment, and few opportunities for leisure. Social media alternates between occasions for worry and outrage…and the promise of relief — in the form of…the mindless scroll…Between working ourselves up and calming ourselves back down, we have created a loop that forecloses the possibility of leisure.

The essay proceeds by investigating Aristotle’s definition of leisure, and Thorstein Veblen’s, and Callard’s own approach when teaching her students—how she sees higher education as permitting a kind of leisure that is difficult to find, and enduringly rewarding.

I wrote about Agnes Callard’s philosophy of aspiration in—

I also loved Celeste Marcus’s ‘“I Am Trying to Live a Life I Do Not Understand”,’ which draws out the particular psychological torment that Marcus—and many others right now—are feeling about American and Israeli politics. ‘I try,’ she writes, ‘to imagine what a world after this, after this political crisis, after this historical paroxysm, will look like.’ What’s happening now feels like a betrayal of the values and loyalties she once held dear:

I used to move through the world armed with a profound sense of received meaning and conscious of the life choices that a serious life required of me. There was a time in my life when my sense of loyalty and honor was so concrete to me that I could rely on my inherited frameworks to give me both a worldview and a course of action…This is no longer true. In so many essential ways the world I was born into does not any longer exist. The countries which I had been raised to love and serve have revealed characteristics so strange I cannot recognize them, so unattractive that I am no longer pulled toward them, though I still derive meaning from my loyalty to… them? To my idea of them? To a version of them for which I try to fight and in which I tell myself I still believe? If honor is a matter of loyalty, then honor will mean something new to me now.

The New York Review of Books (the January 15, 2026 issue) ✦

This is my third year subscribing to The New York Review of Books, which publishes 20 issues a year for $130 (although I always subscribe when they’re running a deal with the Paris Review). I usually read 4 issues in full, 6 or 7 incompletely, and quiver with terror when faced with the remaining unread issues.

This year, I’m doing my best to at least open all of the issues. I’ve only read half of the January 15 issue so far, but what I’ve read so far has been exceptional.

If you’re mostly a fiction reader, you’ll enjoy Kevin Power’s ‘All the Sad Unliterary Men,’ which is a review of David Szalay’s Flesh, one of the best novels I read last year:

And the novelist Yiyun Li’s ‘A Talent for Living’ explicitly discusses Beryl Bainbridge's novels, but implicitly offers some lessons for reading and living. ‘To die is an awfully big adventure, and so is to live,’ Li observes. Living requires you to endure small and large forms of suffering—no matter what age you are. Towards the end of the review, Li describes the young characters in Bainbridge’s The Death of the Heart:

…the children whose minds are mirrors—loyal or distorting, who can tell—of the shabbiness of the grown-up world. But perhaps this applies to all those whose talent for living and feeling leads to a deeper pain—a timeless situation that renders the characters ageless. As Bowen puts it, “Everybody who suffers is the same age.”

If you’re in a nonfiction mood, I loved the art historian Susan Tallman’s ‘The Empire Gives Back’ and the climate activist Bill McKibben’s ‘It’s a Gas.’

Tallman’s ‘The Empire Gives Back’ is about whether museums can, and should, repatriate museum artifacts to their original homes. The answer isn’t always obvious, even if Tallman—and the two historians/curators she discusses, Bénédicte Savoy and Dan Hicks—firmly believe in cultural restitution. ‘Today,’ Tallman writes,

The thoroughness with which colonized people were robbed of their own creations seems unconscionable…90 to 95 percent of the historical patrimony of sub-Saharan Africa is held outside the continent. The problem is not just that the West has so much; it’s that everybody else was left with so little…Precisely because our museums have successfully sensitized us to the incandescent power of art objects, [Savoy, in her book Who Owns Beauty?] asks, “how can we not want…to engage in a fairer policy towards the dispossessed?”

But there are numerous political, legal, and financial difficulties involved in repatriation, as Tallman illustrates, and even when you ‘consider to whom these objects should rightly belong…it’s not a slam dunk’ when it comes to returning them. She also criticizes the overburdened form of guilt and self-abasement that is common with Western intellectuals. Of Dan Hicks’s recent book, Tallman writes:

It is clear that Hicks’s book is deeply felt, but as with much recent postcolonial rhetoric in the museum world, there is something self-aggrandizing about the self-abasement, the persistent conviction that the West must be truly special—if not better, then at least worse than everybody else. The problem is, there’s just too much competition. The crimes of European colonialism were novel insofar as new technologies allowed them to be conducted at greater scale and with a cover story of rationality rather than just divine preference. But the practice of stealing from victims and rendering them anonymous while monumentalizing victors is a human constant, especially if we acknowledge oral traditions as a form of monument. There are no innocent empires. Read up on Ashurbanipal and you may never sleep again.

I also appreciated the peerless Bill McKibben’s ‘It’s a Gas,’ which opens by summarizing the current state of our climate crisis. He includes a sobering quote from the climate scientist Zeke Hausfather, who coauthored the latest IPCC report:

Things aren’t just getting worse. They’re getting worse faster. We’re actively moving in the wrong direction in a critical period of time that we would need to meet our most ambitious climate goals. Some reports, there’s a silver lining. I don’t think there really is one in this one.

From there, the essay becomes a review of a new book, Peter Brannen’s comprehensive The Story of CO₂ Is the Story of Everything. The story of everything? As McKibben cheekily writes,

I know that you have been promised the story of everything before, only to read an account of rice, or salt, or gunpowder, or cod, or some other interesting commodity. But carbon dioxide is the real deal. If you go back pretty much to the beginning of everything—and Brannen does—you find carbon dioxide lurking in the shadows, controlling events with a power that the Illuminati (or the cod) could only envy.

Art

I’ll close with two painters I recently discovered—thanks to other people’s posts on Substack:

Ludovic Nkoth’s deft, expressive portraits

Ludovic Nkoth is a Cameroonian-American painter living in NYC. He’s had solo shows in Paris, London, and Los Angeles; he’s also been included in group shows in Copenhagen, Chicago and elsewhere.

One of his most striking paintings, Invented Truth, depicts a pensive woman in striped pajamas, gazing a little past the viewer:

I also love Nkoth’s Shadow of a Mirror, which is a beautiful homage to one of Hilma af Klint’s most recognizable paintings:

I discovered Nkoth from ayan artan’s post below—I’m really looking forward to her forthcoming interview with the artist!

Meghann Stephenson’s lavishly austere paintings

After studying illustration at Parsons, Meghann Stephenson lived in NYC and worked with fashion and lifestyle brands like Man Repeller and Bon Appétit. But after several group shows, and then a solo show in late 2024, she’s now primarily known as a painter.

Stephenson’s paintings, with their solemn figures and pristinely radiant surfaces, remind me a lot of the British artist Meredith Frampton’s paintings of the 1920s to 1940s. You might recognize Frampton’s ‘Portrait of a Young Woman’ from the cover of Nabokov’s Ada, or Ardor, newly reissued by Penguin Modern Classics. (I learned this from the writer Ella Dorn’s newsletter on making book covers sexy again.)

But back to Stephenson. There’s a kind of luxurious hauteur to many of her paintings—and a kind of isolating anomie, with the stark backgrounds and isolated hands:

I came across Stephenson’s paintings in a recent newsletter by Emily Grady Dodge, who writes about interior design and personal style.

Thank you for reading this newsletter. Let me know what you’ve enjoyed lately—fiction, nonfiction, essays, poetry, art—in the comments or by replying to this email!

And I’ll return to your inbox soon with a newsletter on platform politics…contemporary philosophy…fashion week…or anti-algorithmic music discovery…I haven’t decided yet!

Here’s one excessively lovely passage in Ziporyn’s translation notes:

A good translation does its job only when a thousand aesthetic and compositional decisions cohere…in a way that brings into focus the life, style, and rhythm of the source text, made to lurk and lilt in the marrow and margins of these efficient and precise structures without corrupting or collapsing them, instead quickening them into an emanation of the interconnected universe of thought, feeling, and word that lives and breathes in the original work.

A long sentence, but whom among us (assuming the ‘us’ is composed of mostly Proust fan) does not love a long sentence…and there are so many exciting alliterative pairs here! Lurk/lilt; marrow/margins; corrupting/collapsing…

I’m only now finishing a Muji candle I bought last May—the orange blossom and yuzu one for £6.95. It’s so fragrant and has a lovely freshness when you’ve been stuck at home all day, and it’s already dark at 4pm.

Does it sound odd to read Aristotle in our time? This is my first time reading Nicomachean Ethics, and I’m amazed by how modern it feels. Almost every major publication today talks about being “high-agency” and making deliberate choices.

What surprised me is that Aristotle was already talking about this 2000 years ago. Different words, same core idea. It doesn’t feel outdated at all. It feels foundational.

I love how broad your newsletter is in terms of subject! being an engineer working in railway signalling who is at the same time passionate about literature, art, travel and interior design means constantly being drawn in a milion different directions - and you seem to be able to combine your various interests so well!