best books, essays, and poems of 2025

an invitation to read more in the new year ✦

‘The new year,’ the writer Oliver Burkeman suggests, ‘should be the moment we commit to dedicating more of our finite hours…to things we genuinely, deeply enjoy doing.’ His bestselling book, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, is deeply concerned with the finite nature of our lives. If we only have, say, four thousand weeks to live a meaningful life, then how should we spend those weeks? The days within those weeks? The hours within those days?

In 2025, I devoted my hours to reading: 80 books in total, including novels, nonfiction, academic monographs, and the stray poetry collection. I don’t read because I’m trying to be a more intelligent, interesting, virtuous person—though books are sometimes helpful in cultivating those traits! Instead, I read because it’s one of the most enjoyable things I could be doing with my attention. An evening alone with a book is restorative and rewarding; an evening alone with my phone, less so.

So if your new year’s resolution is to scroll less and read more, here’s a suggestion. ‘Stop trying so hard to turn yourself into a better person,’ Burkeman writes, ‘and focus instead on actually leading a more absorbing life.’ Chastising yourself for your habitual phone addiction won’t help you change; consciously choosing new activities might:

A much more reliable way to stay offline is just to be doing things so engaging that it wouldn’t occur to you to drift online in the first place. On the few magical days in 2025 that I realised I’d forgotten where my phone even was, it was because I’d become so immersed in reading or writing or conversation or nature that the thought of it had left my mind entirely.

This newsletter is an invitation to immerse yourself in reading—with recommendations for the best books, essays, and poems I read in 2025. The ‘best’ of anything is, of course, deeply subjective and inherently personal, but I hope some of my choices will speak to you—and can be part of a 2026 devoted to reading books, not feeds. Below:

Best novels (for getting back into reading; facing tragedy with humor; and understanding contemporary life)

Best nonfiction (for understanding the history of design, our technological present, and how to handle political differences)

Best essays

Best poems

Best books that defy description (fiction? memoir? essays? poems? other?)

Need more recommendations? I read 110 books in 2024, and 93 books in 2023. My favorites were—

Best novels

4 novels with incredible velocity

If you’re getting back into a reading routine, the best books to read are the ones that require very little effort. They’re not lazy reads, but they are exceptionally easy reads—because you’re drawn in from the first few pages, and ensnared until the very end.

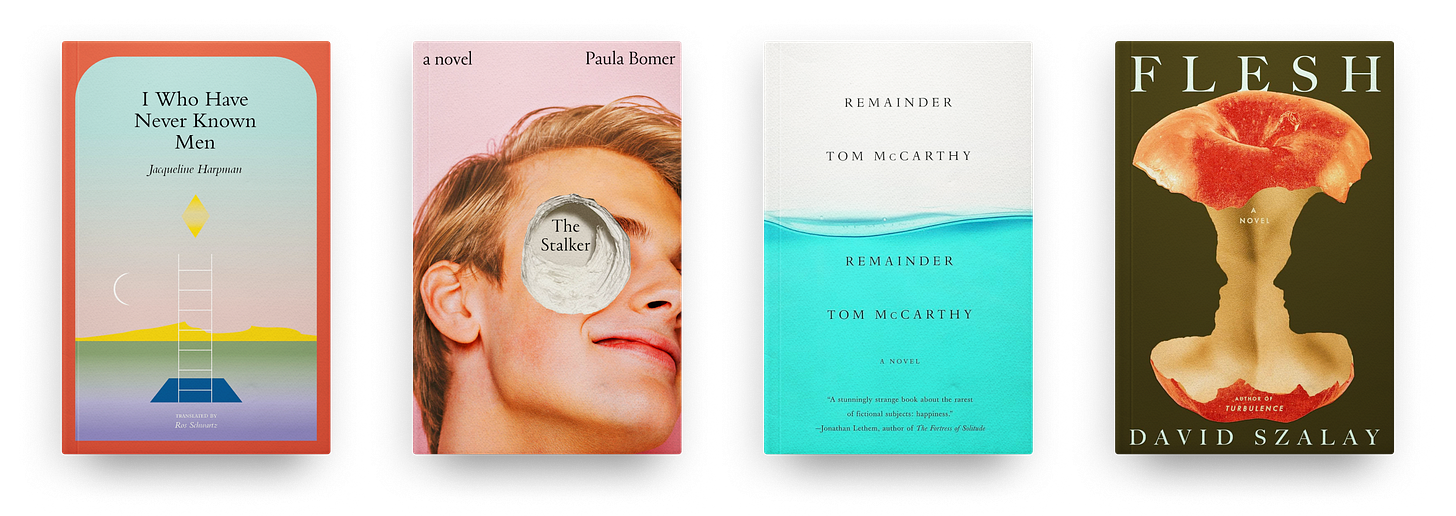

Jacqueline Harpman’s I Who Have Never Known Men (1995, 200 pages), a dystopian novella about a young girl who has spent her entire life imprisoned among other women. If you’ve read and loved Susanna Clarke’s sublime Piranesi—Harpman’s novel is just as compulsively readable and uncanny. I wrote about the novel’s unexpected popularity on Tiktok back in June.

Paula Bomer’s The Stalker (2025, 260 pages), about a revoltingly egocentric man and his attempts to exploit women for sex, money, housing, drugs. Mentioned in my July/August newsletter. Read this if you’re obsessed with sugar baby stories and want the gender-swapped version. Also recommended by my friend Klara Feenstra, who notes: ‘Bomer has an incredible way of managing pace—by the last chapter, time is moving faster than you can read.’

Tom McCarthy’s Remainder (2005, 290 pages), which none other than Zadie Smith described as ‘one of the great English novels of the past ten years’ when it was first published. Here’s how I described it in my September newsletter:

Imagine you’re a man who has enough money (£8.5 million, to be precise) to never have to work again. Imagine, also, that you received this money…after experiencing a traumatic injury that left you bedridden for months and with much of your memory erased. What would you do with your life? Well, if you’re the protagonist of Remainder…you hire an abnormally competent right-hand man named Naz and start orchestrating extremely complex reenactments of certain scenes—half-remembered, actual, fictional—involving paid actors and purpose-built settings. What kinds of scenes? Oh, you know, shootings and bank robberies; nothing major.

David Szalay’s Flesh (2025, 370 pages), which I read after glowing praise from Brandon Taylor, Henry Oliver, and Klara Feenstra again. (It also won the Booker Prize this year, which was judged by the celebrated actress Sarah Jessica Parker, the Irish writer Roddy Doyle, and others.) In my July/August newsletter, I described it as ‘A propulsive rags-to-riches story of a young man, István, who gets caught up in other people’s plans…and dragged through different social and economic classes in Hungary and London.’ Another novel for anyone obsessed with the fantasy—and grim realities—of marrying up.

Looking for shorter (and more sexually frank) books? Try—

4 novels that are funny and tragic

2025 was not a good year, geopolitically (and maybe also personally, although I won’t pry into your affairs). 2026 might be the same. If you’re looking for novels that blend catharsis and levity, misery and hope—these are a good start:

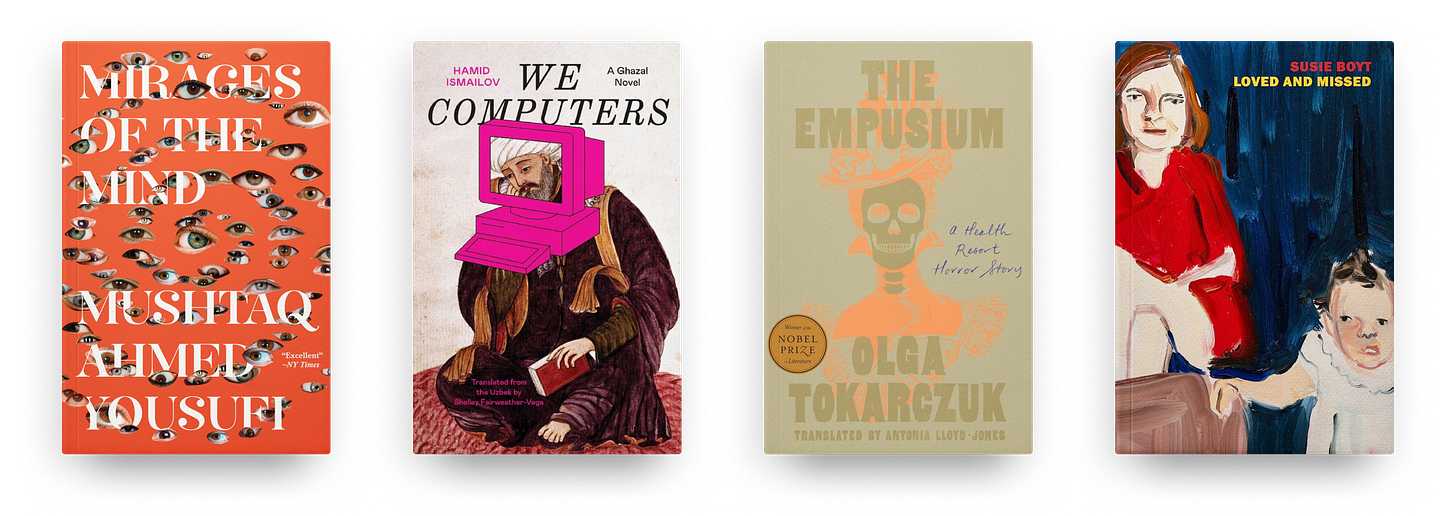

Mushtaq Ahmed Yousufi’s Mirages of the Mind (1990), translated from Urdu by Matt Reeck and Aftab Ahmad, is a novel about British colonialism, religious conflict, and displacement that is mostly really, really funny. Set in post-partition Pakistan, and featuring an enormous cast of extremely memorable characters, the novel reads like a standup routine—where the jokes are about Mughal dynastic succession, ghazal poetry, and the mysterious gendered nouns in Urdu. Here’s how one character, a larger-than life lumber seller named Qibla, is described:

No matter how rational or straightforward you were, he would be sure to refute whatever you said. He considered it unbecoming to agree with anyone. He started each sentence with ‘no.’ One day I said, ‘It’s really cold today.’ He said, ‘No, tomorrow will be colder’…If an unfortunate customer happened to show up [at his shop], he would thunder at him and drive him away. Yet the customer would have to come back. That was because nowhere else in Kanpur could you find such good lumber. He said, ‘I never sell bad wood. Wood shouldn’t be blemished. Blemishes are becoming only on lovers and teenagers’…He didn’t particularly like poetry. He couldn’t stand free verse. Someone said that free verse is like a tennis game without a net, and that person is probably right…In his last days, he was a recluse and a misanthrope; he left the house only to walk in his enemies’ funeral processions.

The novel’s structure feels a bit like traditional oral storytelling: it’s highly digressive and leaps from one character’s life story to the next. One of the more nostalgic–sentimental passages is excerpted in Caravan, which describes the novel as follows:

Vladimir Nabokov called Proust’s enormous novel sequence In Search Of Lost Time “a treasure hunt where the treasure is time and the hiding-place the past.” Something of the same quest is enacted in this excerpt from the great Pakistani writer Mushtaq Ahmed Yousufi’s novel Mirages of the Mind.

Hamid Ismailov’s We Computers (2022/2025), translated from Uzbek by Shelley Fairweather-Vega, is a novel about a French poet-programmer who becomes obsessed with using his computer to generate literature. In 2025, many, many people addressed the question of What AI Will Do To Literature, but I think Ismailov’s novel—as I wrote in my September newsletter—is

one of the most original, sideways explorations of how AI will affect literary authorship and innovation.

In We Computers, the protagonist sometimes laments the lack of romance in his life, but it’s fundamentally a very cheerful, inquisitive novel—because he ends up infatuated with Persian poetry instead. I was so impressed! And I’d like to read more Ismailov in 2026—the esteemed posters of the World Literature Forum are such fans.

Olga Tokarczuk’s The Empusium (2022/2024), translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, is about a sensitive young man staying at a sanatorium in the mountains to recover from tuberculosis. It’s Tokarczuk’s remake of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, and Lloyd-Jones’s translation is just so charming—the novel feels like a cheerfully pastoral story of a young boy finding his place in the world. But there are both overt and covert dangers: unexpected deaths, curiously foreboding passages narrated by a mysterious primeval presence, and the chauvinism of a pre-WWI Europe. I wrote a longer summary—and quoted some of the loveliest passages in the book—in last January’s newsletter.

Susie Boyt’s Loved and Missed (2013) is a novel about dignified living under intolerable conditions. For Ruth, a schoolteacher and single mother, the intolerable conditions—aside from a genteel level of penury—come from her daughter Eleanor’s heroin addiction. When Eleanor gets pregnant, Ruth ends up becoming the primary caretaker for her granddaughter, Lily—and while their close relationship helps in managing the contaminating shame and difficulty of Eleanor’s addiction, the novel makes it clear that salvation isn’t total. In my October/November newsletter, I wrote that ‘This is a novel about adult life, which means it’s a novel about the wavering reparations we can make for the past.’ It’s amazing how carefully optimistic, and even lighthearted, the novel can feel—even though it’s tragic and painful and will almost certainly make you cry. My longtime friend Laurel Clayton also wrote about Loved and Missed here.

Would you rather read some straight-up depressing novels? Try—

3 novels about the contemporary condition

The present! It’s full of difficulty and misery and excitement and agony! The great themes of literature—sex, romance, love, money, status, insecurity, fame, and envy—appear in every decade’s novels. But if you want these themes depicted in more familiar settings, try these novels:

Eva Baltasar’s Permafrost (2018), translated from Catalan by Julia Sanches, is a very funny novel about typically depressing topics: a young woman’s lesbian romantic langour; feeling distant from her (very heterosexual) family, and persistent suicidal ideation.

Stephanie Wambugu’s Lonely Crowds (2025) is an impeccably written Künstlerroman about two young Black women pursuing artistic careers in very white, very moneyed settings: first at a liberal arts college on the east coast, where they both receive scholarships, and then in ‘90s NYC. This is astonishingly well-written; I almost can’t believe this is Wambugu’s first novel, since it feels so artistically mature and fully realized.

More on the novel (and the incredible dynamism and interpersonal insight in Wambugu’s writing) in my October/November newsletter.

Zoe Dubno’s Happiness and Love (2025) is also a Künstlerroman about a young person trying to become an artist. But the novel begins on a more satirical and cynical note than Lonely Crowds. In Dubno’s book, the narrator is trying to escape a claustrophobic circle of art-world friends who are status-conscious, shallow, and self-obsessed. Unfortunately, she ends up trapped at a memorial service–slash–dinner party with everyone she’d trying to distance herself from. Happiness and Love is explicitly inspired by Thomas Bernhard, but Dubno’s great accomplishment is that she transmits the deep idealism at the core of Bernhard’s novels—not just the surface-level disgust with society. More on Dubno’s novel in my October/November newsletter; I also found myself delivering a spirited defense of it on a dance floor at 7 AM on Halloween weekend…that’s true dedication to literature.

Best nonfiction

The best nonfiction books, I think, are written by people who really cherish novels—and draw from all the typically novelistic techniques of descriptive scene-setting, carefully deployed dialogue, and the overarching awareness that what people need is a story, not just a sequence of facts:

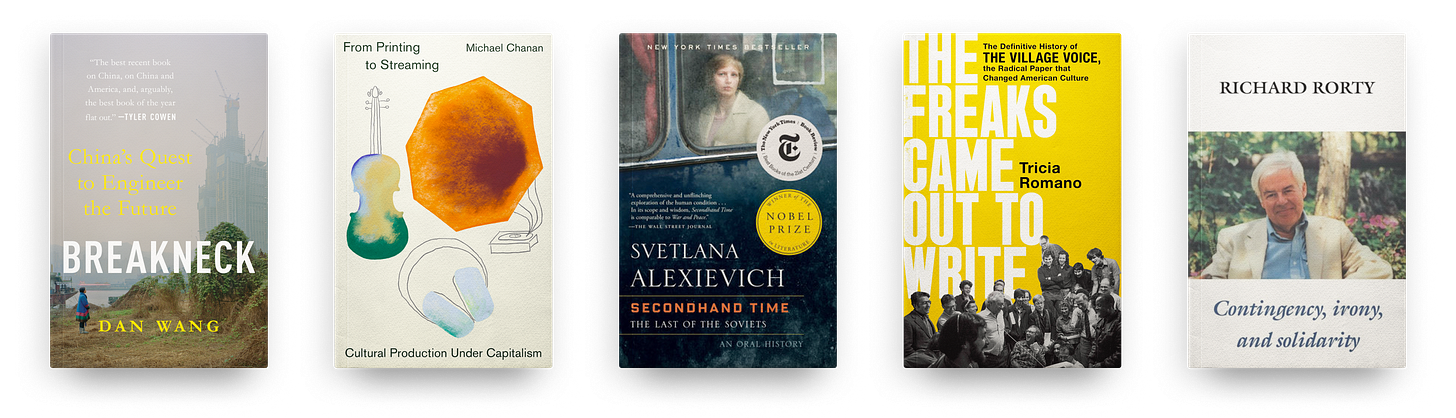

Dan Wang, Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future (2025) has already received a great deal of praise, and I included a 500-word summary of the best ideas (and nonfiction writing techniques!) in my October/November newsletter. In brief: a well-researched, elegantly written book about China’s quest for scientific, technological, and economic dominance over the past few decades. I loved Wang’s concept of ‘process knowledge,’ and it’s a useful way of understanding how expertise—in design and technology especially—is transmitted.

Michael Chanan’s From Printing to Streaming: Cultural Production under Capitalism (2022) is, as I wrote in my October/November newsletter:

…a book of Marxist cultural analysis for people who find such books particularly stifling…and has the immodest goal of serving as a history of cultural production, authorship, copyright, and monetization—in literature, music, and cinema—from the 15th century to the present day (though Chanan largely focuses on the 18th century onwards).

It’s magisterial in scope, occasionally humorous, and only has 5 ratings on Goodreads! This, to me, is an outrage; it’s such an excellent book.

Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets (2013). Alexeivich is an investigative journalist and Nobel literature laureate, and Secondhand Time is an oral history book about the disintegration of the Soviet Union that draws together a number of touching, funny, heartbreaking stories of ‘history running roughshod over people’s lives,’ as I wrote in my July/August newsletter.

Tricia Romano’s The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture (2024) is an effervescent and entertaining oral history of the renowned alt-weekly newspaper, the Village Voice. In a review essay I wrote for Asterisk Magazine, I suggested that:

The Village Voice was, essentially, the Bell Labs of cultural criticism. Both institutions were founded in New York City…Both were tremendously innovative in their respective fields: The researchers at Bell Labs invented the transistor, the programming language C, UNIX, and the discipline of information theory. The editors and writers of the Voice, meanwhile, were early advocates of influential musical genres (rock music, disco, hip-hop) and ideas (auteur theory in film) — all in the pioneering style of New Journalism, where literary techniques were used to produce criticism and reportage steeped in subjective experience. Alt-weeklies like the Voice, observed its former executive editor Kit Rachlis, showed that “writing about culture was an extraordinarily important thing … to cover, write about, report on, think about, analyze.” And the Voice’s writers weren’t just tastemakers; they also shaped the American political landscape, covering Trump’s early property dealings, judicial corruption, the nascent feminist movement, the AIDS crisis, and ACT UP.

Richard Rorty’s Contingency, Irony, Solidarity (1989) is one of the great works of American pragmatism. It’s 50% philosophy, 50% literary criticism, and proposes how—despite the epistemic difficulties of articulating what real, ethical liberal politics might look like—we can still find a way to reduce cruelty in the world and deepen our understanding of other people’s subjective experiences. It’s hard to describe, but Rorty’s book really moved me—and it’s shaping the kind of intellectual work I want to do in 2026. I’d like to write more about it; for now, you can read this excellent essay by George Scialabba on Rorty’s Contingency, Irony, Solidarity. Scialabba’s forthcoming book, The Sealed Envelope: Towards an Intelligent Utopia, has even more on Rorty—and other thinkers like Christopher Lasch and Barbara Ehrenreich.

Best essays

I try my best to read books on my commute, but sometimes it’s easier to stare at my phone. Essays are perfect in these situations: shorter (so you can finish them before arriving at work!) and just as intellectually rigorous, complex, elegantly written, and exciting.

Here are 14 of my favorite essays published in 2025—in magazines like The Point, The New York Review of Books, Harper’s Magazine, Asterisk Magazine, but also in Substack newsletters by great novelists/critics/intellectuals:

Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s ‘Left-Wing Irony’ in The Point (February), which has an exceptional analysis of right-wing irony and left-wing failures (both electorally and stylistically) to combat it:

How should the left counter right-wing irony, if not by adopting the same destructive rhetorical strategies as Trump, or else slipping back into its own contemptuous habits?…But there are, happily, other options. In particular, other types of irony. A more productive left-wing irony might be rooted not in the ideological certainty of the smug critic—the “know-all” irony of Benjamin’s “spiritual elite”—but in ideological humility. The irony, that is, of holding two thoughts in mind at once: my experience, and yours.

Sam Kriss’s ‘Alt Lit’ in The Point (February), which performs a close reading of the ‘cool and possibly evil scene’ that is alt lit. (‘Alternative to what?’ Kriss asks.)

Sally Rooney’s ‘Angles of Approach’ in the NYRB (March), about talent, excellence, and snooker.

Sheon Han’s ‘Inside arXiv—the Most Transformative Platform in All of Science’ in Wired (March), about the open-access repository that makes scientific research easier to access and share:

Visit arXiv.org today (it’s pronounced like “archive”) and you’ll still see its old-school Web 1.0 design,…But arXiv’s unassuming facade belies the tectonic reconfiguration it set off in the scientific community. If arXiv were to stop functioning, scientists from every corner of the planet would suffer an immediate and profound disruption…For scientists, imagining a world without arXiv is like the rest of us imagining one without public libraries or GPS.

Vivian Gornick’s ‘The 176-Year Argument’ in the NYRB (April), on the City College of New York, ‘the first tuition-free school of higher learning in the country’:

We were the children of tailors, shopkeepers, factory workers; accountants, bakers, dress cutters; clerks, milkmen, bus drivers…And there you had City College: unworldliness eclipsed by the insights of lived experience…a writer who had taught at two posh schools and then at City College said, “At Chicago all they wanted to know was, What’s the theory? At Yale all they wanted to know was, What’s the technique? At City all they wanted to know was, How does this relate to real life?”

kate wagner’s ‘some essays on how to write essays’ in her newsletter (July):

My best advice when it comes to choosing a subject: nothing is irrelevant. History is a continuum in which everything is irrevocably enmeshed, and the system of relations is by its very nature infinite…If you’re a good writer, you can make anything interesting and the only way to become a good writer in this vein is to write about everything, even if you think you won’t be good at it, because the only way to become good at something is to do it. So goes, unfortunately, the tautology of practice.

Elvia Wilk’s ‘The Unbearable Lightness’ in the NY Review of Architecture (August). An investigation into the horrors of artificial lighting, from the 19th century to present:

Derek Neal’s ‘Attention is All We Need: On Leif Weatherby’s Language Machines’ in 3 Quarks Daily:

Ismail Ibrahim’s ‘House Arab’ in Bidoun (September), about working at the New Yorker as the magazine’s only Arabic-speaking fact-checker during the genocide in Gaza. Also excerpted in Harper’s.

Chris Marino’s ‘The Death of Cool’ in his newsletter (September):

A defining characteristic of 2020s New York culture is that the performance of being an artist has taken precedence over the production of art. The ingenuity of contemporary artists, their capacity for imagination, mystery, and style, is channeled into the creation of appearances, vibes, and happenings, of suggested bohemian worlds, rather than the fabrication of free-standing works of visual, literary, or musical art.

afra’s ‘The China Tech Canon’ in Asterisk (October) on the philosophers, historians, and novelists read by Chinese technologists:

Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem has become for China what Asimov’s Foundation was for the United States: a literary scaffolding for thinking about technology, geopolitics, and the fate of civilizations…[The] novels minted phrases that have since entered China’s everyday political and business lexicon…treating Liu’s cosmic metaphors as diagnostic tools for China’s entrepreneurial reality.

Daniel Kolitz’s ‘The Goon Squad’ in Harper’s (November). An anthropological examination of…well.

Think about it for a second: What are these gooners actually doing? Wasting hours each day consuming short-form video content. Chasing intensities of sensation across platforms. Parasocially fixating on microcelebrities who want their money…abjuring connective, other-directed pleasures for the comfort of staring at screens alone. Does any of this sound familiar? Do you maybe know some folks who get up to stuff like this? It’s true that gooners are masturbating while they engage in these behaviors. You could say that only makes them more honest.

Amia Srinivasan’s ‘The Impossible Patient’ in the LRB (December) on the history of psychonanalysis and how it emerged from ‘an aestheticised culture of feeling and self-cultivation that resulted from political paralysis.’

Despite more than a century of debate about the epistemic credentials of psychoanalysis, I take its explanatory power to be self-evident…You may reasonably object to many of the details of the orthodox Freudian picture…But can we doubt that there is more, much more, to our individual and collective lives than that of which we are consciously aware? Do we doubt that each of us encounters reality not directly, but through the thicket of our individual psychic realities, with their stubborn frames and secret desires, the vast sediment of our past histories?

Patrick Nathan’s ‘The Horror of the Husband,’ in his newsletter (December), which offers an elegant typology of literary novels:

If you wanted to be irritating, you could distill the history of the modern literary novel down to two characters whose infidelities drive each to suicide. Even better is their polarity: one is tragic, the other comic; and ever after we have Anna novels or Emma novels — a beautiful and bereft mother sobbing as she throws herself on to the brutal tracks of modernity; and a bloated, bankrupt philistine puking up arsenic while a villager sings a vulgar tune…The previous century belonged to Anna stories — Cheever, Updike, and Salter are the most obvious examples — but our own is an Emma era: Franzen’s Joey Berglund digging through his own shit to retrieve a wedding ring; or, more recently, Ada Calhoun’s Crush, in which a husband’s forthright “wouldn’t it be hot if you kissed other men” unwittingly unravels their marriage.

Want to read more great essays (and learn how to write them, too)? Try—

Best poetry

People tend to have very polarized feelings about poetry. It’s too inaccessible, too difficult to ‘get’; or it’s too intimate, soppy, unsubtle. But the more poetry I read, the more I feel that there’s a poem for every person—and a poem for every minor variation of feeling in your life.

My feelings tend towards cautious nostalgia, obscure forms of sadness, intellectualization/abstraction, and total immersion in artistic experience. If this description appeals to you, here are 8 poems I fell in love with last year:

Hua Xi’s ‘A Table’ in the New Yorker (2025), which begins:

I was trying to measure my mother’s sadness with a very long ruler.

She talked at me from one end of a sentence.

A sentence the length of a table.

Everything I say to my mother begins so far away.

In Athens. Under fruiting olives. On Plato’s ideal table.

Just now, I set my glasses down on a thousand-year-old idea.

I’m always moved by by the unguardedness of Xi’s poetry—there is a beautiful candor and vulnerability to a line that simply says: Everything I say to my mother begins so far away. The language feels so literal, so transparent, that I’m caught off-guard by Just now, I set my glasses down on a thousand-year-old idea: the verbs and nouns pin down abstract concepts (‘ideas,’ ‘Plato’) and make them memorably concrete.

Divyasri Krishnan’s ‘Parlor Hour’ in The Yale Review (2025), which is very brief, very expressive:

I prefer windows to mirrors. To see

at once where I am and not.

I’ve been subscribed to Krishnan’s newsletter for some time, but hadn’t read this poem until she sent out her end-of-year email. For anyone who’s beginning 2026 a little self-conscious about their age, and self-conscious about what they haven’t accomplished, Krishnan has some encouraging words:

I’m not sad to be older…I used to impose personal timelines for my achievements, impossible ones, and tear myself apart for missing them: novel by 16, marathon by 18, PhD by 25, etc. Of course, none of it happened. But no more of that. I want only to make use of my time…to wake up with something to do, and go to sleep with something done. Even if it’s almost nothing to anyone else. All that matters is what it is to me.

Éireann Lorsung’s ‘Simile’ from Pattern-book (2025). Lorsung was born in Minneapolis and is now a writing professor in Dublin. The poem begins:

How does a simile work?

— Place something next to something

and say, here. (The here is where

the somethings touch.) The rainy

night, like Debussy…I’m drawn to ‘Simile’ because I have that typically modernist instinct—I love poems about poetry, paintings about paintings (it’s why I like John Baldessari so much). Thanks to the writer Loré Yessuf for sharing this in her excellent poembutter newsletter.

Amit Majmudar’s ‘Critical Theory’ in the NYRB (2025), a poem about poems:

The poem as trick pony rooting in a feed bag full of truth

The poem as wonder cabinet stocked with whatever was close at hand

The poem as celestial tinnitus, transmissible as sniffles…

The poem as a 3D printout of a point in time…Majmudar’s collection, Things My Grandmother Said, comes out in April.

Victoria Chang’s ‘The Swan, No. 20 (Hilma af Klint)’ in the NYRB (2025). When I first discovered Chang’s Obit poems—which take the form of newspaper-like obituaries of things like ‘My Mother’s Teeth,’ ‘Memory,’ and ‘Friendships’—I remember thinking: Oh, so this is what contemporary poetry can do! Her poems have this beautiful, introspective hesitancy; you feel the narrator (is it correct to say poems have narrators?) and their thoughts as a live, trembling presence. Here’s how this new poem of hers begins:

The canvas is flipped from right to left. But the shell is smaller. All morning I thought the shell was the same shell. That it was a seashell. But maybe it’s a snail shell. I knew my placement of the shell on the beach couldn’t have lasted. Now my mind must move. In our lives how many things are like the snail, never thought of?

aria’s ‘Waiting for Your Call’ (2021), which has an extraordinary opening line—I love how easily she evokes the atmosphere that the poem takes place in, using 2 words that aren’t typically used to convey visual information (‘retreat,’ ‘generous’):

The light retreats and is generous again.

No you to speak of, anywhere—neither in vicinity nor distance,so I look at the blue water, the snowy egret, the lace of its feathers

shaking in the wind, the lake—no, I am lying.There are no egrets here, no water. Most of the time,

my mind gnaws on such ridiculous fictions…For the Proust fans, Aber has two poems that touch on him: ‘Zelda Fitzgerald’ (the first Aber poem I read!) and ‘Afghan Funeral in Paris.’

Muriel Rukeyser’s poem from Speed of Darkness (1968), which I first read in Yessuf’s poembutter newsletter. Though it was written several decades ago, it feels uncomfortably familiar now—I’m writing this after a morning spent reading about Caracas, Minneapolis, Portland, Tehran:

I lived in the first century of world wars.

Most mornings I would be more or less insane,

The newspapers would arrive with their careless stories,

The news would pour out of various devices

Interrupted by attempts to sell products to the unseen.

I would call my friends on other devices;

They would be more or less mad for similar reasons…

All the poems in Ruth Krauss’s There’s a little ambiguity over there among the bluebells (1968 as well—clearly a year of great poetic interest to me!), which I wrote about in June, but especially this one:

I’m looking forward to a spring filled with poetry! I have a copy of David Gorin’s To a Distant Country waiting for me at my childhood home in California, and a few other collections in the mail.

Best books that defy description

Not novels. Not nonfiction. Not poetry. But some special fourth thing—3 books that are sublimely evocative, artistically innovative, and deeply enjoyable to read:

Helen Garner’s How to End a Story: Collected Diaries (2025) was my main companion during the 2 weeks I was sick with Covid and could barely crawl out of bed. Thankfully, the renowned Australian writer is almost effortless to read—her diaries are full of compelling and instantly memorable descriptions of people in her lives (or strangers on the street). A deeply rewarding read, especially if you’re trying to carve out time in your life for a literary or artistic practice:

Karen An-hwei Lee’s The Maze of Transparencies (2019) is a novel about society after the collapse of a cloud-computing surveillance state. I read it on the recommendation of my friend/flatmate (and also a profoundly fascinating writer) Philip, and in my October/November newsletter, I offered a brief plot summary:

Yang is a former data scientist (of a kind) who now tends to a very Berkeley Bowl–esque garden and calculates everything using his family’s jade abacus. It’s a charming post-computing fable, narrated by one of the clouds that Yang used to log into, Penny (short for Penelope the Predictive Panoply of People’s Data). In between stories of Yang’s encounters with various strangers, Penny broods over the technically advanced (but politically corrupt) past, and the strangely low-tech present…You’ll either love or hate this book. I loved it: the worldbuilding is lovely and strange and charming; and as a Californian, I tend to enjoy books that exuberantly pilfer nouns from the health-food aisle.

And here’s one of the poems in Lee’s novel:

Rainald Goetz’s Rave (1998/2020), translated from German by Nate West, is the original first-person rave retelling. In my October/November newsletter, I wrote that:

There’s an art to writing about raving; the best works distill the phenomenological (and insistently embodied) feeling of the dancefloor (and, sometimes, the drugs that might accompany the experience) into prose. Not all of it can be distilled, of course—reading about a party is no replacement for being there yourself. But Rave gets close…the book—sharp, funny, cogent—moves nicely between the intellectual and the insistently sensorial…And West’s translation has real velocity and flow to it—transmitting the ebb and flow of the narrator’s journey from party to party, city to city, nighttime to daylight.

Sick of raves? Sick of rave writing? Here’s a quote to convince you that Goetz’s book is worth a look:

Now that I’ve discussed the 19 books, 14 essays, and 8 poems that I fell in love with last year…I’ll leave you with one final recommendation:

Take your reading life seriously! Take yourself—your mind, your interests, your passions, your intellect—as seriously as possible. If life is richer when you’re online, you don’t have to escape the internet; instead, you can use the internet to deepen your literary experiences. But if you feel that life might be more rewarding with a little less time staring at a screen, then I hope you’ll turn towards some of the books I’ve shared.

If you end up reading any of my recommendations, please let me know! And thank you for spending some of the finite time of your life reading my newsletter. Wishing you a beautiful January and a promising start to 2026.

wake up babe celine dropped another banger

It occurs to me that under "Books That Defy Description" you might enjoy M. John Harrison's "Wish I Was Here" (also his novel, The Course of the Heart, which is more conventional in structure but gorgeously weird in the ways that count).