annie ernaux fixed my disintegrating attention span

the (almost) definitive ranking of Ernaux's books ✦ everything I read in March, April, and May 2025

It is moderately embarrassing to write a newsletter about literature and then struggle to finish books. For most of March, I kept on trying to read—Middlemarch; Nietzche’s aphorisms; Émile Zola’s Nana; a history of probability—and couldn’t finish any of them. I’d get 50 pages in and lose interest.

Two years ago, faced with a similarly attenuated attention span, I decided to focus on one book: the literary scholar Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature.1 This spring, though, I couldn’t concentrate—I restlessly skipped between books and felt profoundly disappointed in everything. Which book, which writer, could restore me?

What got me out of my reading recession was Annie Ernaux, a woman from a working class family who became, over the course of several decades and over 20 books, one of France’s most well-known writers. When she won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature, the committee wrote that:

Ernaux's work is uncompromising and written in plain language, scraped clean. And when she with great courage and clinical acuity reveals the agony of the experience of class, describing shame, humiliation, jealousy or inability to see who you are, she has achieved something admirable and enduring.

What made Ernaux so easy for me to read? Well, her books are (for the most part) very short. They’re disarmingly direct and visceral and personal: she writes about her love affairs, going grocery shopping, and observing strangers on public transit. All this makes for easy and appealing reading—but Ernaux almost always includes an unsparing, intense look at French history, social class, and gender relations.

But it was also because I’d learned something from February (a hectic month for me, personally and professionally) about how to get back into reading:

Create an arbitrary emergency. In late March—when I was struggling to read—my friend Nile and I booked tickets to the final performance of The Years, a play adaptation of Ernaux’s works at a theater in London. I’d already read her book The Years, along with 4 other works—but because the play was supposed to draw from Ernaux’s entire oeuvre, I decided to try and read as many of her books as possible before seeing the play on April 19.2

Don’t read alone. It helped that my friend (a true “acolyte of Annie,” as he put it) had already read 7 of her books when we booked the tickets! We ended up competing (not very acrimoniously) to see who could read more Ernaux. (I lost.)

Do it out of love and curiosity, not out of obligation. I began this year with a specific reading goals: more 19th century novels, more philosophy, more nonfiction. I haven’t given up on these goals, but it was enormously helpful to just—let go of them, temporarily, and read something purely fun.

Earlier this year, I wrote about how I created an “arbitrary emergency” to help me read Hannah Arendt—

All this helped me read, from March through May:

9 books by Annie Ernaux, in an attempt to create a definitive ranking of all of Ernaux’s books—the ones translated into English, at least. The incomplete ranking is below! It includes 13 books, with 6 I still haven’t read…

…but reading Ernaux gave me enough energy to finish 5 other, very petite books—a chapbook about John Cage; a Californian poet’s biography (presented, naturally, as a poem); TikTok’s favorite translated Belgian novella; and a ghost story featuring Edvard Munch’s paintings

The (almost) definitive ranking of Annie Ernaux’s books

In a recent newsletter, the novelist and critic Naomi Kanakia suggested that “highbrow literature has acquired a fandom.” Well, fans need t-shirts, so my friend made these for us to wear to see The Years at the Harold Pinter Theatre:

Before seeing the play, though, I had to pay my dues as an acolyte of Annie…and read as many of her books as possible.

What are Ernaux’s books like?

The 3 great themes in Annie Ernaux’s writing are:

Collective society and history: Many of Ernaux’s books are about things like social class and mobility, post-WWII prosperity, consumer culture, youth activism, aging and death…but she explores these topics in a very concrete way. I love how Ernaux writes about shared spaces (like the grocery store or transit stations) because her books are never just about buying groceries or observing a stranger on a commute! She might, for example, look at her purchases and make a fleeting observation about how “Every item suddenly takes on loaded meaning, reveals my lifestyle. A bottle of champagne, two bottles of wine, fresh milk and organic Emmental, crustless sandwich bread, Sveltesse yogurt…” Or she’ll note, in passing, how women’s autonomy and economic participation have changed in the last few decades. As the critic and memoirist jamie hood wrote, in a review for The Baffler:

[Because] her private life is also a woman’s life…much of this work has expressly labored to account for the radical transformations to women’s familial, erotic, and political possibilities over the last fifty years.

Social class, and the shame and defiance that comes from being working class. Ernaux’s most moving writing, in my opinion, happens when she reflects on her origins and the humble lives her parents led—and how her education and literary success lifted her out of that world and into a new, rarefied world, one that she never quite feels at home in. In her Nobel lecture, she described how difficult it is for “those who, as immigrants, no longer speak their parents’ language, and those who, as class defectors, no longer have quite the same language” to write about their lives.

Sexuality and desire: One of the reasons Ernaux is so easy to read is that she writes a lot about love and sex. Half of her books are obsessive, feverish accounts of a love affair—or her acute jealousy when a lover is unavailable to her. You’ll either love or hate this side of Ernaux. As jamie hood (the superlative Ernaux critic?) writes in Bookforum, Ernaux “is a superlative archivist of heterosexual pleasure—one of the last living straight girl icons.”

Which books I’d recommend, and which ones I’d skip

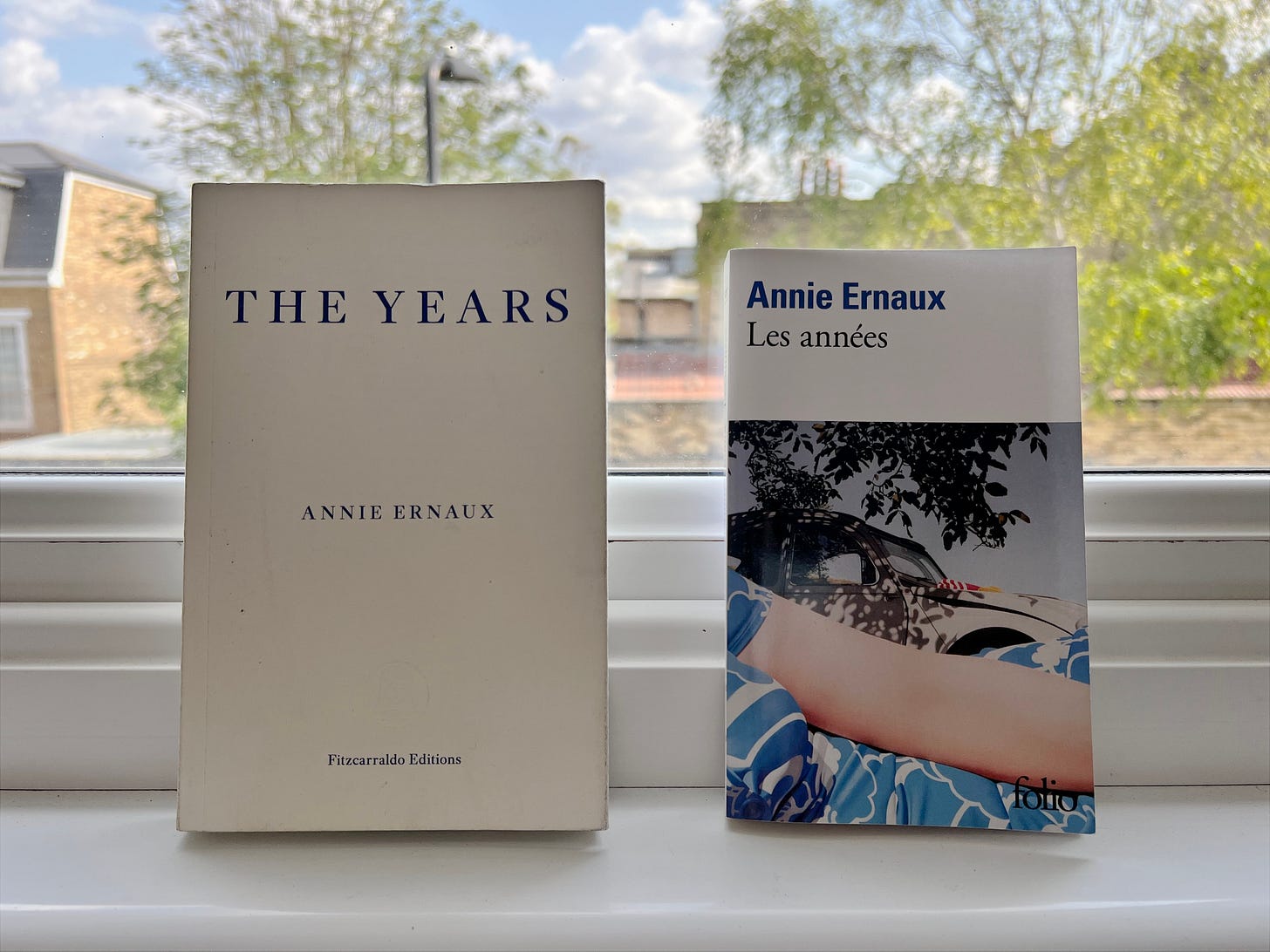

The Years (published in 2008) is Ernaux’s great masterpiece. If you read just one book, it has to be The Years! It begins in 1941, just after Ernaux was born, and narrates six decades of her life through images, stories, and memories of world events: the end of WWII, the American and Soviet race to the moon, France’s defeat at Điện Biên Phủ, the Algerian War, May ‘68, Saddam Hussein’s rise to power, Gorbachev’s fall from grace. (“Leningrad was St. Petersburg again,” Ernaux writes, “much more convenient for finding one’s way around the novels of Dostoyevsky.”) The novel is largely told with we, even when Ernaux describes scenes from her childhood, her home, her life as a daughter, teacher, wife, mother, divorcée, writer. In most autobiographies, Ernaux said in an interview,

we speak about ourselves and the events are the background. I have reversed this. This is the story of events and progress and everything that has changed in 60 years…transmitted through the “we” and “them”. The events in my book belong to everyone, to history, to sociology.3

A Man’s Place (1983) is a portrait of Ernaux’s father, written years after he passed away. It begins with a carefully neutral, almost unemotional description of his death—then plunges into the past, describing her father’s upbringing on a farm, his early life working at an oil refinery and starting a small shop with his young wife, and always “above the poverty line, but only just.” Ernaux describes, too, the mixture of pride, alienation, and estrangement that her father showed as she became academically successful, more well-spoken, more bourgeois—part of a world that her father could never, with his lack of education and rural origins, be a part of. A Man’s Place, along with the next 2 books in my ranking, beautifully depict Ernaux’s desire to remember and honor her origins:

As I write, I try to steer a middle course between rehabilitating a lifestyle generally considered to be inferior, and denouncing the feelings of estrangement it brings with it. This was the way we lived and so of course we were happy although we realized the humiliating limitations of our class…I would like to convey both the happiness and the alienation we felt. Instead, it seems that I am constantly wavering between the two.4

Shame (1997) is also exceptional and one of her most affecting books. It begins on the afternoon of June 15, 1952, “the first date I remember with unerring accuracy from my childhood.” Ernaux, twelve years old, returns from school and sees her father—in the middle of an argument—threaten to kill her mother. This memory, Ernaux writes, left her with a penetrating, indelible sense of shame—shame about her origins, her family, and her class position. The rest of the book describes her upbringing in Yvetot, and the behaviours and manners of the people she grew up with, and how disorienting was for her to encounter—when her academic accomplishments brought her to a private boarding school—students from much more respectable, bourgeois backgrounds. Also an excellent, penetrating, and very moving portrait of social class in 20th century France.

I Will Write to Avenge My People (2023) is the speech Ernaux gave when accepting her Nobel Prize in late 2022. It’s easy to recommend this because it’s very short and contextualizes her overall project as a writer:

Written in my diary sixty years ago. ‘I will write to avenge my people, j’écrirai pour venger ma race’…I was twenty-two, studying literature in a provincial faculty with the daughters and sons of the local bourgeoisie…I proudly and naively believed that writing books, becoming a writer, as the last in a line of landless labourers, factory workers and shopkeepers, people despised for their manners, their accent, their lack of education, would be enough to redress the social injustice linked to social class at birth. That an individual victory could erase centuries of domination and poverty, an illusion that school had already fostered in me by dint of my academic success. How could my personal achievement have redeemed any of the humiliations and offences suffered? That’s not a question I ever asked myself.5

Happening (2000), along with Shame and her Nobel lecture, feel like her most explicitly political books. While the other 2 focus on class issues, Happening is about abortion access and how it affects the lives of women, especially working-class women. It largely takes place in the autumn of 1963, when Ernaux—a university student at the time—gets pregnant. Abortion is illegal in France, although women from well-off families can still find someone to help them. But Ernaux, a poor, working-class student, struggles for months to find a way out.

Time ceased to be a series of meaningless days punctuated by university talks and lectures, afternoons spent in cafés and at the library, leading up to exams and the summer vacation, to the future. It became a shapeless entity growing inside me which had to be destroyed at all costs…Born into a family of laborers and storekeepers, I was the first to attend higher education and so had been spared both factory work and commerce. Yet neither my baccalauréat nor my B.A. in liberal arts had waived that inescapable fatality of the working-class—the legacy of poverty—embodied by both the pregnant girl and the alcoholic.6

In the first few months of 1964, Ernaux meets with Madame P-R, a woman who performs an illegal abortion and sends her home. The description of the abortion is unflinchingly horrible—and apparently someone in the audience fainted when it was performed in the play The Years—and Ernaux doesn’t gloss over the trauma and difficulty she experienced. Happening is an unsparing and difficult read—especially as an American, especially since Roe v. Wade has been overturned. But it’s also Ernaux at her best—she shows how personal experiences are inextricably caught up in political and social issues.

Look at the Lights, My Love (2014) is one of my personal favorites. I love books that are about ordinary, domestic life, and this book draws from a year’s worth of supermarket shopping trips to describe French life and society in the early 2010s. “The spirit of the times,” Ernaux writes, “decides what is worth remembering”:

Writers, artists, filmmakers play a role in the elaboration of this memory. Superstores, which over the past forty years in France the majority of people visit roughly fifty times a year, are only starting to be considered as places worthy of representation. Yet I realize, looking back in time, that for every period of my life I retain images of big-box superstores, with scenes, meetings, and people.

I wrote about my fascination with everyday life—and how it’s depicted in literature!—in my very first newsletter:

Exteriors (1993) is also a personal favorite, but if you aren’t as obsessed with semi-sociological portraits of collective life and city life, this may be a bit less interesting to you! It’s similar to Look at the Lights, My Love!, except it’s set in the RER, the rapid transit and commuter rail system that serves Paris and the nearby suburbs. The book, Ernaux writes,

is neither reportage nor a study of urban sociology, but an attempt to convey the reality of an epoch—and in particular that acute yet indefinable feeling of modernity associated with a new town…I believe that desire, frustration and social and cultural inequality are reflected…in anything that appears to be unimportant and meaningless simply because it is familiar or ordinary.7

Getting Lost (2001) is an engrossing, profoundly gripping story of an affair—I guess the contemporary term is situationship—that Ernaux had with a Soviet attaché in Paris. It’s set in 1989 (just before the fall of the Berlin wall) and is composed of Ernaux’s diary entries, lightly edited, from that time. It’s very, very compelling and a fascinating look at erotic obsession…but if you read this first, you’ll probably come away thinking: She won a Nobel for this? I’m a huge Getting Lost defender, though, because of this one exceptional quote:

For five years, I've ceased to experience with shame what can be experienced with pleasure and triumph (sexuality, jealousy, class differences). Shame spreads over everything, prevents any further progress.8

I personally think that you can stop after Getting Lost and basically “get” what Ernaux’s literary project is! But if you’re a true completionist—or a 68% completionist, like me—you can continue on to:

The Use of Photography (2005), written with the photographer and journalist Marc Marie, chronicles Marie and Ernaux’s passionate relationship. Each section of the boook begins with a photograph taken of their clothing and shoes, abandoned on the floor after an assignation, and then a brief essay written by each of them reflecting on the photograph. What makes this book especially touching is that it begins with Ernaux’s breast cancer diagnosis—and the juxtaposition of life-affirming events (sex) and events that forcibly remind Ernaux of her mortality (chemo appointments) is very powerful. An interesting project (Marie and Ernaux wrote their passages without looking at the other person’s text) but not a necessary read…

Simple Passion (1991) is the worse version of Getting Lost. It’s the novel version of Ernaux’s affair, and was presumably edited to be more readable than the diaries…but I really think it lacks the immediacy and vitality of Getting Lost! If you’re a true acolyte of Annie, it’s worth reading both—it’s rare that you get to read the raw material and the finished version of a story! But if you can only read one, please read Getting Lost.

The Young Man (2022) is—I mean, is it bad to say it’s one of the more mid works in Ernaux’s oeuvre? The Young Man is about Ernaux’s liaison, at 54, with a much younger man in university. Ah, so it’s like the film Babygirl, you may be thinking—but what I liked best about The Young Man is the passages where Ernaux reflects on her working class origins, and how—despite being, at this point, firmly ensconced in the French literary establishment—she’s still attached to her humble beginnings. “Thirty years earlier,” she writes, I would have turned away from him… I would not have wanted to be confronted with the signs of my working-class origins in a boy.” Now, as the older woman, she can introduce him to “literature, theater, bourgeois customs”—the domains that she struggled to enter and feel at home in. It’s a charming story, but the writing isn’t as powerful as her other books about social class (A Man’s Place, Shame) or love (Getting Lost).

The final 2 books on my list are ones that I—and I really hate to say it—didn’t really like? If I wasn’t trying to read as much Ernaux as possible before seeing the play version of The Years, I wouldn’t have finished these:

A Girl’s Story (2016) is about a formative experience in Ernaux’s adolescence, in the summer of 1958. She was one of the youngest and newest counselors at a summer camp, and after a sexual encounter with a popular, older counselor, she ends up rejected and mocked by the rest of the counselors. This is a genuinely difficult read—it describes the desperation to be desired, and how easy it is for young girls to be sexually manipulated and then shamed, in a very visceral way. But I think it’s poorly constructed (compared to her other memoir-y books, at least) and loses steam halfway through. As my friend Nile noted, it feels like something she had to write—to grasp at some catharsis or self-acceptance—but it doesn’t feel very whole and integrated as a story.

The Possession (2022) is about Ernaux’s all-consuming jealousy when a former lover (who she left, after 6 years together) begins a relationship with someone new: a 47 year old professor, divorced, with a young son. When the former lover tells Ernaux this, she—burdened with these biographical details—becomes obsessed with learning more about this woman. What does she look like? Where does she teach? What is her life like? “The strangest thing about jealousy,” Ernaux writes, “is that it can populate an entire city—the whole world—with a person you may never have met.” If you are given to stalking your exes (or your ex’s exes, or your partner’s exes) on social media, this could be a very cathartic read! Or if you liked vol. 5 and 6 of In Search of Lost Time, which describe the protagonist’s obsessive, neurotic jealousy that his loved one might be seeing others. But I—despite being an exceptional, world-class ruminator—don’t really look people up on social media like that, so I couldn’t get into The Possession! Especially since there is much less about class, gender, and French history compared to her other books.

What happens when you bring Ernaux to the stage?

My weeks of near-total Ernaux immersion (I’m not sure if I read anything else, except a few stray social media posts and Substack newsletters) made me very excited to finally watch The Years at the Harold Pinter Theatre in London.

The play, adapted by the Norwegian theater director Eline Arbo, takes its narrative structure from The Years—but it includes lots of scenes from other Ernaux books.9 Five actresses (Deborah Findlay, Gina McKee, Tuppence Middleton, Anjli Mohindra and Harmony Rose-Bremner) take turns acting as Ernaux at different stages of her life. The rest of the actresses then serve as Ernaux’s parents, lovers, children, friends…

This approach—of shifting who plays Ernaux—led to very comic moments. In one scene from Ernaux’s early years as a mother, the 2 oldest actresses play as Ernaux’s young sons—squabbling at the dinner table, flinging food around, eating in a cheerfully grubby manner. It’s just funny to see two grey-haired women perfectly reenact the blobby, inexact movements of a child!

It was also fun, as a partial Ernaux completionist, to notice how many scenes from other books were included in the script—especially ones from Happening (the abortion) and A Girl’s Story (the first sexual encounter) and Getting Lost (the all-consuming affair).

Seeing the play was a beautiful climactic moment—which, unfortunately, meant that my desire to be an Annie Ernaux completionist has just…disappeared. I still have 6 works to read (Cleaned Out, Do What They Say or Else, A Frozen Woman. A Woman’s Story, I Remain in Darkness, and Things Seen—I’m including only the ones translated into English). But I may hold off on those until early 2026, when Seven Stories publishes Writing, the Other Life, which includes some new Ernaux writing!

Books that weren’t Ernaux

My newly restored attention span (thank you, Annie Ernaux) helped me read 5 other books, too—they’re all very short, but sometimes that’s what you need when restoring a reading habit!

The (im)perfections of millennial life

I read Vincent Latronico’s Perfection, a novel shortlisted for the 2025 International Booker Prize. I was excited to read this—it’s meant to be a contemporary version of the French writer Georges Perec’s Things: A Story of the Sixties, and I love Perec!—but the novel was underwhelming.

Perfection follows a young European couple, Tom and Anna, and their aesthetically aspirational (and neurotically tasteful) life as freelance creatives in Berlin. It’s an exceptionally faithful account of that strange and performative period of the 2010s that gave rise to things like monsteras in every millennial’s apartment, and altars to consumerist branding like the @onmyeames Instagram (which Tom and Anna would certainly have come across). But I didn’t feel that there was any particular emotional thrust to the story—Tom and Anna want to live a nice life, and they drift around Europe trying to find it, but it all feels very vague. As Rachel Connolly wrote in her review for The Telegraph, “Tom and Anna…seem void of the wills and wants that define what I, and other millennials who actually exist, understand to be the human condition.”

A tiny, tiny book about John Cage

In late April, I went to Tenderbooks (one of the loveliest bookshops in London) for an event with Atelier Édition, an independent publisher whose Faith in Arts chapbooks feature various artists associated with the Black Mountain College. The school was founded in 1933, in rural North Carolina, and “fostered the talents of numerous artists during the uniquely hopeful and propulsive period that followed World War II,” as Amanda Fortini wrote.

I bought a copy of John Cage: Art, Life & Zen (which is now sold out) and read nearly all of it on the bus ride home. These are tiny books, but very satisfying! I love small chapbooks; they’re very adorable…

I wrote a newsletter last year about John Cage and what AI artists can learn from his work—

A biography in the shape of a poem

A few years ago, I read the novelist Lisa Hsiao Chen’s Activities of Daily Living, and was particularly struck by the epigraph, which quoted from the poet Lyn Hejinian’s The Fatalist:

Time is filled with beginners. You are right. Now each of them is working on something and it matters. The large increments of life must not go by unrecognized.

There was something so loose, open, warm, and generous about these lines. I knew I wanted to read more of Hejinian’s work. But I didn’t get around to it until she passed away in February last year, and all the obituaries and essays finally pushed me to buy a copy of My Life, one of Hejinian’s most famous works.

Born in the Bay Area, Hejinian spent much of her life in Berkeley, California—publishing poetry books; collaborating with artists, musicians, and filmmakers; and teaching at UC Berkeley. My Life is an oblique kind of autobiography—a collection of prose poems, which advanced chronologically through Hejinian’s life. The earliest ones draw from her childhood; the poems at the end are about her life as a poet, teacher, mother.

Certain themes recur (an awareness of the future: “I was an object of time, filled with dread”), along with certain images (ribbons, roses, points, lines). I struggle to describe poetry without sounding a bit unsteady, uncertain about it all—but My Life is a tremendous pleasure to read, because it uses such direct nouns and verbs, and then deploys them in such unexpected ways. “Rough utter cold,” one poem ends. “Which makes it a coat of crystal.”

This was a book that languished on my shelves for ages—I started it a year ago, and put it aside for months—but I’m glad I found it now. Sometimes you finish a book at exactly the right time.

The BookTok pick that is genuinely very good

You may have heard of this book: I Who Have Never Known Men, by the previously unknown Belgian writer Jacqueline Harpman. In early January, Emily Gould wrote about how how BookTok made this ‘90s novel an unexpected hit. When Transit Press, a publisher based in Oakland, California, reprinted it in 2022,

“It sold what you would expect for a Belgian book in translation that came out 30 years ago,” says Transit publisher Adam Z. Levy, which is to say, a couple thousand copies. A year later, monthly sales began to pick up, starting at 2,000 that June, then doubling or tripling from month to month until it sold 100,000 copies in 2024. By way of comparison, the press’s most popular titles — mostly high literary fiction in translation — tend to sell in the low thousands. The book’s exponential sales growth initially flummoxed Transit, which sometimes struggles to print enough copies to keep up with demand. Still, Levy admits, it’s a good problem to have.

This is an amazing book to read if your attention span is disintegrating and you’re struggling to read. The first-person narrator is a young girl who has spent her entire life imprisoned with 29 other women. They have no idea why they’re imprisoned, why they’re all women, why their captors are so keen on providing them with adequate food and (barely) adequate attire, why they’re forbidden from touching or embracing each other. This mystery makes I Who Have Never Known Men incredibly interesting—it’s almost as engrossing as Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi (another story set in an obscurely dystopian world, and one of my favorite speculative fiction novels).

No one writes about art like Ali Smith

I ended May with the Scottish writer Ali Smith’s So In the Spruce Forest, a ghost story originally written to accompany an exhibition of the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch’s paintings. The book is a mere 45 pages or so, and about a third of that is Munch’s art—so calling this a book may be stretching the definition a bit…

But the book is so beautiful. (And even more beautiful because it’s so brief!) Smith is a revered and cherished writer in the UK, but not—I think—widely read in the United States. She deserves to be. She writes about what it’s like to directly encounter art in a very simple, unadorned, but also exceptionally beautiful way.

So In the Spruce Forest begins with Ali Smith looking at an 1899 Munch painting on her computer screen, observing it closely (“Look at that bright pool of light to the left. Where’s it coming from in all this approaching night?”) and wondering what it’s showing, when she hears a voice. The voice turns out to be Smith’s mother, who passed away 3 years ago. Throughout their conversation, Smith meditates on topics like the difficulty of translation, the beauty and solitude of nature, and how her working-class origins shaped how she approaches art:

In all our years I never once talked about art with [my mother]. I knew nothing about it myself for most of those years, and then when I did start to be interested I knew she found it perverse, irrelevant, a frippery, the kind of thing people turned towards to avoid the realities of life. And there'd be no money in knowing about it, it wouldn't help you survive in the real world, would it? My parents were by experience practical people; my mother the most intelligent person I've ever known, and what I know now, and couldn't know then, and this isn't how she'd have seen it at all, is that she was the seventh child in a family of nine children growing up fatherless in a country brutalised by religious division and social exclusion.

Life? Hard. Art? Occasionally she loved a picture. There was that print of the bluebell wood she bought in Woolworths when she and my father were first married; my father was furious, they had almost no money and she had wasted money on a picture. After she died he threw it out.

So In the Spruce Forest is quite similar to the approach that Ali Smith takes in her seasonal quartet (4 novels, titled Autumn, Winter, Spring, and Summer)—beautiful, unfussy writing about art and loss. Smith is an exceptional writer, and this book was the perfect way to end the month of May.

Thank you for reading, and accompanying me on my (embarrassing? exciting?) excursion into Annie Ernaux’s oeuvre…t-shirts and all…

If you’ve read this far, I’d love to hear how your reading life is going! And if you’ve recently fallen into a reading rut, how did you feel about it—sad? ashamed? secure and at peace?—and how did you get out of it?

What’s amazing about Auerbach’s book is that he really means it when he says it’s about The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. He’s working with an immense time period—beginning with the Odyssey (750–650 BCE)…and ending with Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927).

And an immense range of languages, too: Homeric Greek, Latin, medieval French (for The Song of Roland), vernacular Italian (for Dante’s The Divine Comedy), Spanish (for Cervantes’s Don Quixote), German (for a play by Friedrich Schiller)…and English (for Woolf).

It’s an exceptional book! I wrote more about Auerbach here—

If you include her Nobel Prize lecture, which was published under the title I Will Write to Avenge My People, Ernaux has 24 books total. 5 haven’t been translated into English yet, which means I just had to read 19 books…

The Years is translated by Alison L. Strayer.

A Man’s Place is translated by Tanya Leslie.

I Will Write to Avenge My People is translated by Alison L. Strayer and Sophie Lewis.

Happening is translated by Tanya Leslie.

Exteriors is translated by Tanya Leslie.

Getting Lost is translated by Alison L. Strayer.

In an interview with the Guardian, Arbo mentioned that she is adapting James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room next, and then the Austrian novelist Marlen Haushofer’s The Wall. I’d really love to see both—Arbo’s adaptation of The Years was so genuinely brilliant, and I’m excited to see how she translates these 2 novels to the stage.

My tried and true method for dealing with reading issues is indeed to just read smaller books. You end up racking up a bunch of simple wins and eventually you get inspired to tackle a bigger project. I also try to zero in on smaller books when I'm gathering reading in bookstores, because I have this consuming voracity for more books than I can read, and i start to feel bad about the time and space and money. smaller books take up less of all.

Middlemarch in paritcular i think is nearly impossible to finish without making it a dedicated project; for me, anyway, I would not have finished it without a book club i'm very passionate about with a friend.

was so excited to see this in my inbox! your newsletters have been so instrumental in getting me back into reading properly -- there really is nothing else like watching someone model a deep, abiding love for literature to get you excited about literature again.

some of the books that have been helping me ease back into reading: cormac mccarthy's the road (just so compulsively readable, so spare and beautiful, and also so tender for a mccarthy novel??) & seth dickinson's the traitor baru cormorant (really fascinating anti-imperialist hard fantasy centered around a young lesbian from an island nation who works within the empire that colonized her home, aiming to take it down from the inside...) & currently buried in many half-finished books but... one of the most exciting ones so far is allen bratton's henry henry (a contemporary reimagining of shakespeare's henriad, delightfully gay, with an eye to the various abuses of hereditary aristocracy).

ernaux is going on my infinitely expanding to-read list!! i love how ardently you engage in comprehensive scholarship of an author's life work & the cultural/social context in which they worked.