we've created a society where artists can't make any money

on artistic innovation, cultural stagnation, and the decline of Silicon Valley intellectualism

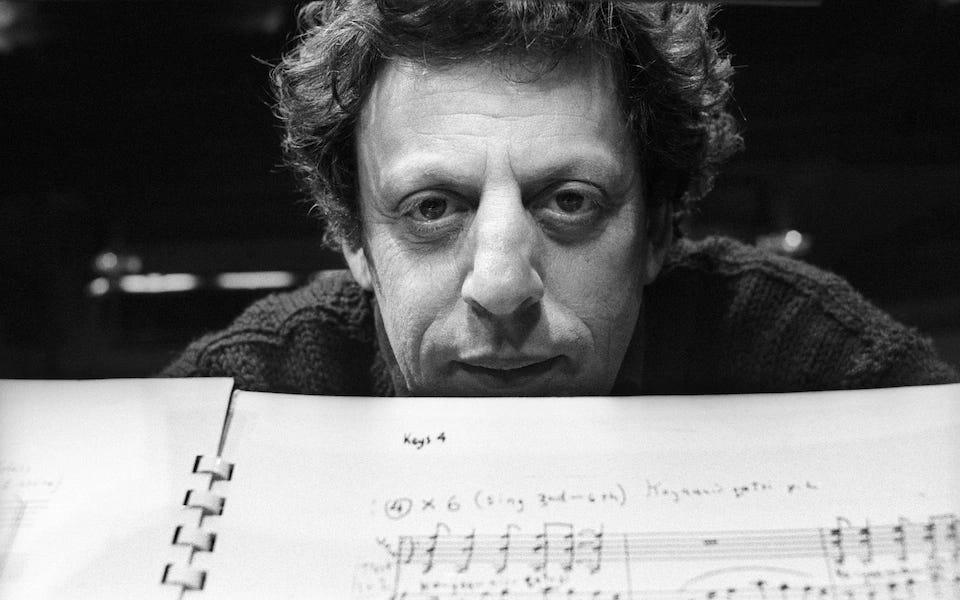

I had never seriously thought about how writers made money, until I began writing myself. I’d read about the starving artists of the past, of course: Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is now considered one of the great masterpieces of American literature, but when Melville passed away at 72, the novel was out of print and even misspelled in his obituary. And the composer Philip Glass was a part-time plumber and taxi driver—while his work was being performed at the Metropolitan Opera in NYC. (As Ted Gioia notes, Glass spent two decades working blue-collar jobs, until he could afford to compose full-time.)

But surely only the avant-garde artists and writers struggled like this—the tragically innovative, the irrevocably original. Those with more commercial work—art directors, illustrators, DJs, journalists, critics—surely they were making money?

I received $50 for the first book review I published, and $0 for the third, but that seemed normal: I was new to this.

But the more I wrote, the more mysterious the question of money became. I was learning how to pitch, how to get commissioned, how to file drafts, how to send invoices. The invoices were always small, but I had a day job, so it didn’t matter. But something wasn’t adding up.

It seemed impossible that anyone could make a living as a writer—certainly not as a literary critic, invoicing $50 for one piece and $500 for another. It seemed impossible, I realized, because it was impossible.

I began to realize that the writers and artists I admired had day jobs that they rarely disclosed online, or partners supporting them, or parents. The most successful writers had tenure-track professorships—but did success grant them the secure job, or secure job enable the success? Others held staff jobs at newspapers, though they seemed to get laid off every 2 years. Others freelanced, tweeting about their latest bylines, bounced checks, renting with roommates, and shouldering the burden of hospital bills, student loans, insurance premiums.

A woman I admired told me, with a rare and fortifying candor, that she could only write literary criticism because her partner supported them both.

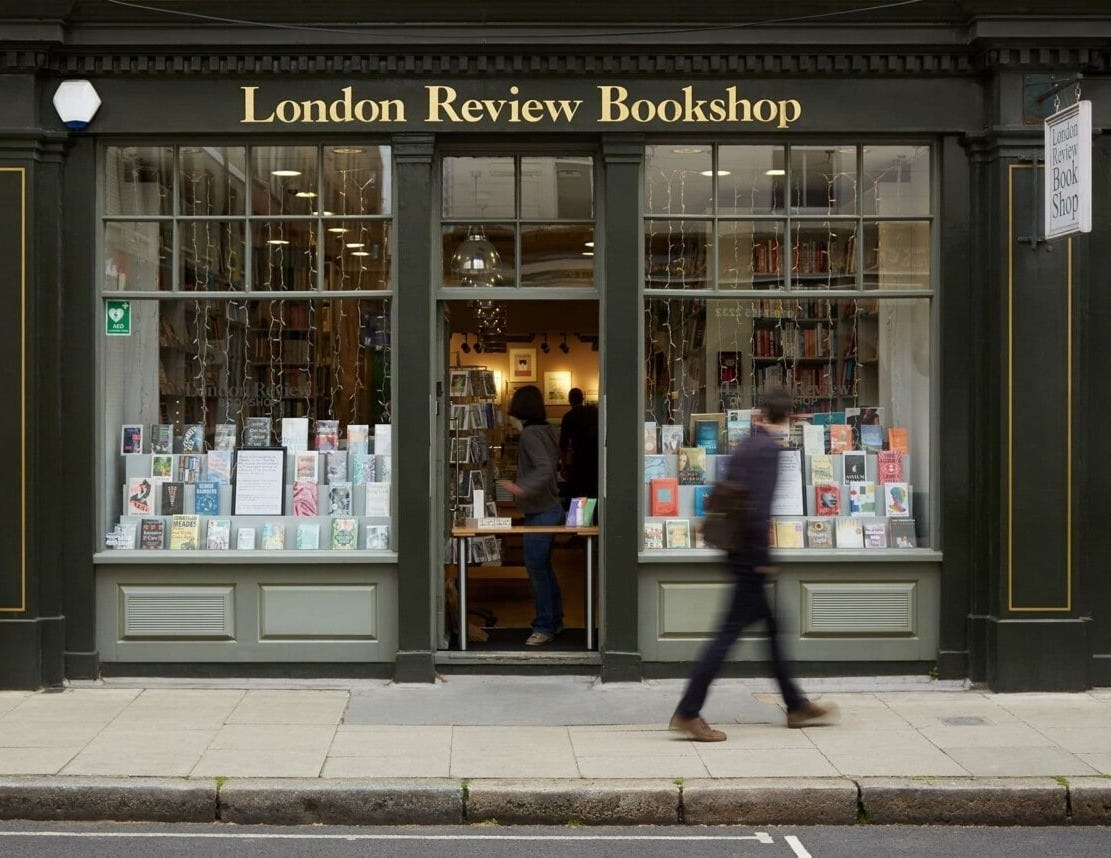

I began to realize that many of the essays I read—in prestigious and well-known magazines—were edited and written and fact-checked by people barely able to make a living from their work. Many magazines were labors of love; others were underwritten by a generous donor or a government grant. (The London Review of Books, I learned, operates at a loss: £27 million since the magazine was founded. It’s thanks to a former editor’s family trust that they’re able to continue publishing.)

On evenings when I wasn’t trying to read these magazines—when I succumbed to the infinite scroll and opened up a social media app—I would see post after post, take after take, about how everything was getting worse. Pop music was getting worse. Indie music. Dance music. Visual art, poetry, films, furniture—all of it was degrading, all of it was in decline.

People blamed this decline on different causes: wokeness, anti-wokeness, the entrenched elites, the unwashed pedestrian masses, too much elitism, too little gatekeeping, the rise of poptimism, a general lack of discernment.

The writer W. David Marx’s latest book, Blank Space: A Cultural History of the Twenty-First Century (November 2025), argues that this narrative of decline is true—that art and culture are less innovative than before. I wanted to review Blank Space because Marx’s first two books (Ametora and Status and Culture) were exceptionally good…and because I wanted to understand if I agreed with him. Were things really getting worse? And did the question of money—how little of it there seemed to be, how precarious cultural labor was—have something to do with it?

You can read my review essay below, or on Asterisk Magazine’s elegantly designed website:

But this newsletter is about how I pitched, researched, and wrote my essay—and what I learned about art, culture, and money in the process.

From June to September last year, while I was working on my essay, several publications—including the New York Times, Vanity Fair, and the Chicago Tribune—announced that they were cutting their books coverage. I couldn’t help but incorporate these events into my essay: it’s 30% about Blank Space and 70% about the economic conditions that shape cultural production and criticism. Writing the essay is also why, in October last year, I signed onto the following open letter—

—and by the end of this newsletter, it should be clear why I feel so strongly about the project of cultural criticism, and why it’s necessary for artistic innovation.

This is part of an informal series on how I pitch, research, and write book reviews. If you want to read more—

Cultural criticism and Silicon Valley intellectualism

Most book reviews begin with a pitch: a condensed summary of what you want to review, what angle you’re taking, and why it matters to the magazine’s audience. The ideal pitch will resonate with the magazine’s existing readers (and their interests!), while also offering something new.

Asterisk Magazine is a relatively young magazine (the first issue was published in November 2022) with an unusual audience. Based in Berkeley, California, the quarterly publication is, as the about page notes, ‘shaped by the philosophy of effective altruism, but not limited to it.’ When the journalist Andrew Marantz wrote about Asterisk in the New Yorker, he described it as ‘a handsomely designed print magazine that has become the house journal of the A.I.-safety scene.’

But the editors of Asterisk have commissioned articles across a wide range of topics: technological, political, sociological. The first article I read was about the myth of the loneliness epidemic; the second was a deep dive into a New Deal government agency’s efforts to bring electricity to rural America. Asterisk has published sober articles on how Trump’s funding cuts have affected America, including an interview with Robert Rosenbaum about directing private donors towards programs that were affected by USAID funding cuts; and a succinct analysis of how scientific research will be affected by reduced funding and immigration policy changes.

This range of topics might surprise you, especially if your understanding of effective altruism is shaped by figures like Sam Bankman-Fried (a minor celebrity and prominent donor within the movement, before he was convicted of money laundering). Effective altruism, which coalesced from the late 2000s onwards, uses utilitarian philosophy to advocate for a certain style of philanthropy and socially-beneficial work. The movement stresses measurable impact over vague feelings of benevolence. But bad actors like like Bankman-Fried have made effective altruism seem morally bankrupt as a movement.1

It doesn’t help that EA is associated with awkward AI engineers and egocentric Silicon Valley nerds. To people outside the tech industry, effective altruism appears passé and essentially cringe. The rationalist blogosphere it grew out of looks even more embarrassing. It’s hard to take rationalists seriously—when one of their near-canonical founding texts is a digressive, 660,000-word Harry Potter fanfiction (about half the length of Proust) where Bayesian reasoning and magical powers are on equal footing.

Here’s where I confess, though, a certain affinity for effective altruism. Though I’m apprehensive about many aspects of the community—a myopic disinterest in electoral politics; an obsession with long-term existential risk over nearer-term AI harm—EA has shaped many of my moral instincts. It’s why I stopped eating meat; it’s why I had a recurring donation to Against Malaria for many years; it’s why I work in climate tech today.

It’s why I believe that whatever privileges I have (growing up upper-middle-class in the United States, for example) also confer an obligation to the greater good. Many philosophical traditions and religions advocate for this responsibility, but effective altruism was the one that, in my early twenties, convinced me.

So I wanted to draw from this tradition for my Asterisk essay—even though I found Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality fatally boring and over-written; even though I find the community’s obsession with existential risk a little aggravating.

Renovating the rationalist image

The best explainer I’ve come across for the rationalist community is the writer and programmer Sheon’s ‘Rat Traps,’ for the tenth issue of Asterisk. ‘For those of us who move within liberal or progressive circles,’ he writes:

Openly admitting one’s readership of the rationalist genre can feel like a social misstep…For one, the rationalist community has the reputation of leaning libertarian…[but in] the closest thing to a census of the community…35% identify as “liberal” and 30% as “social democratic.”

But Han, like me, has a certain fondness for the community:

From when I first discovered the rationalist blogosphere in 2015 until it began to grow tedious (more on that later), it was a proportionally small but stimulating portion of my media diet. I consumed it like a psychoactive pill, one that made me slightly insane but alert to other kinds of insanities. I found it to be frequently insightful, sometimes obvious, often annoying and rather pompous, regularly helpful, and — for a group lampooned for its emotional aridity — unexpectedly vulnerable.

This vulnerability can make rationalists look ridiculous, especially when they over-analyze and over-theorize the parts of life that should come naturally. But what is natural, really? Is it natural to know how to make friends, how to fall in love, how to live according to your values?

And the rationalist style of reasoning from first principles—in a distinctively curious, humble, open-minded way—seemed ideally suited to writing about W. David Marx’s Blank Space. How else could I try to answer questions like—

Is it true that culture is stagnating?

If so, why?

Where does artistic innovation come from?

If artistic innovation is declining, how do we fix that?

—all extravagantly, ludicrously difficult to answer definitively? It was the rationalist tradition that gave me the courage to try. In the process, I also wanted to recover a different strain of Silicon Valley intellectualism—one that, in the post-DOGE era, is worth remembering.

A different side of Silicon Valley

The public image of the tech industry has gone downhill since 2016, when Trump’s unexpected presidential victory prompted a mass re-evaluation of how social media and internet technologies have reshaped society. Prior to 2016, there was something of a liberal consensus that Facebook, Twitter and similar sites were inherently supportive of liberal democracy, as the sociologist Zeynep Tufekçi observes in her book Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest.

This changed after 2016. People stopped believing that tech companies like Google could deliver on their stated values, like ‘Don’t be evil.’ And books like Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger (2023) and Angela Nagle’s Kill All Normies (2017) analyzed how online forums and social media platforms were used for revanchist, alt-right political projects.

This reevaluation of the tech industry also meant that tech culture—and its most visible figures—became more suspect. The most vilified oligarchs of the 2000s were hedge fund managers and other finance-industry figures; in the 2020s, it’s tech CEOs like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Alex Karp.

But the nakedly profit-seeking side of Silicon Valley has always shared space with other ideological inclinations. In a newsletter sent last February, the political scientist Henry Farrell wrote about ‘a very different Silicon Valley culture, which has been obscured by Musk, DOGE and the cult of the founders.’ Farrell first encountered this culture in 2009, when the programmer and organizer Aaron Swartz invited him, and several other social scientists, to speak at a tech ‘unconference’:

What struck me…was the culture’s combination of open-endedness and personal modesty…People wanted to make things better, but they didn’t assume that they knew exactly how to. They were curious, and they listened.

Aaron himself represented many of the best aspects of this culture. He was a member of the first graduating class of Y Combinator, but was not…the kind of founder with aspirations to grandeur. What he excelled at was connecting people, and spotting ways to help them. The first couple of years after his death, I kept discovering about his lengthy correspondences with people whom I had never known he had known, with wildly varying ideologies, woven together into a kind of invisible intellectual republic of people who usually did not realize that they had Aaron in common.2

As the ambitions of Silicon Valley elites grew, this intellectually plural culture of joyful weirdness and problem solving has shriveled and diminished. It’s still there, but it’s not nearly as visible or strong as it used to be.

It was this intellectually plural culture that made me fall in love with technology. As a young girl growing up in Silicon Valley, I read tens, maybe hundreds of blogs during the heyday of RSS—about architecture, interior design, software engineering, fashion, beauty, startups, typography. I never felt conflicted about my interest in girly things and nerdy things; only later did I feel an enforced societal pressure to choose a lane, to narrow my interests. (One of the most violent things you can do to a young woman’s intellectual development, I feel, is to convince her that she has to be a ‘math person’ or a ‘humanities person,’ and not both.)

And this intellectually plural culture celebrated different forms of knowledge—it rejected the myopic self-satisfaction of seeing STEM disciplines as superior to others.

Hackers, painters, and politically progressive programmers

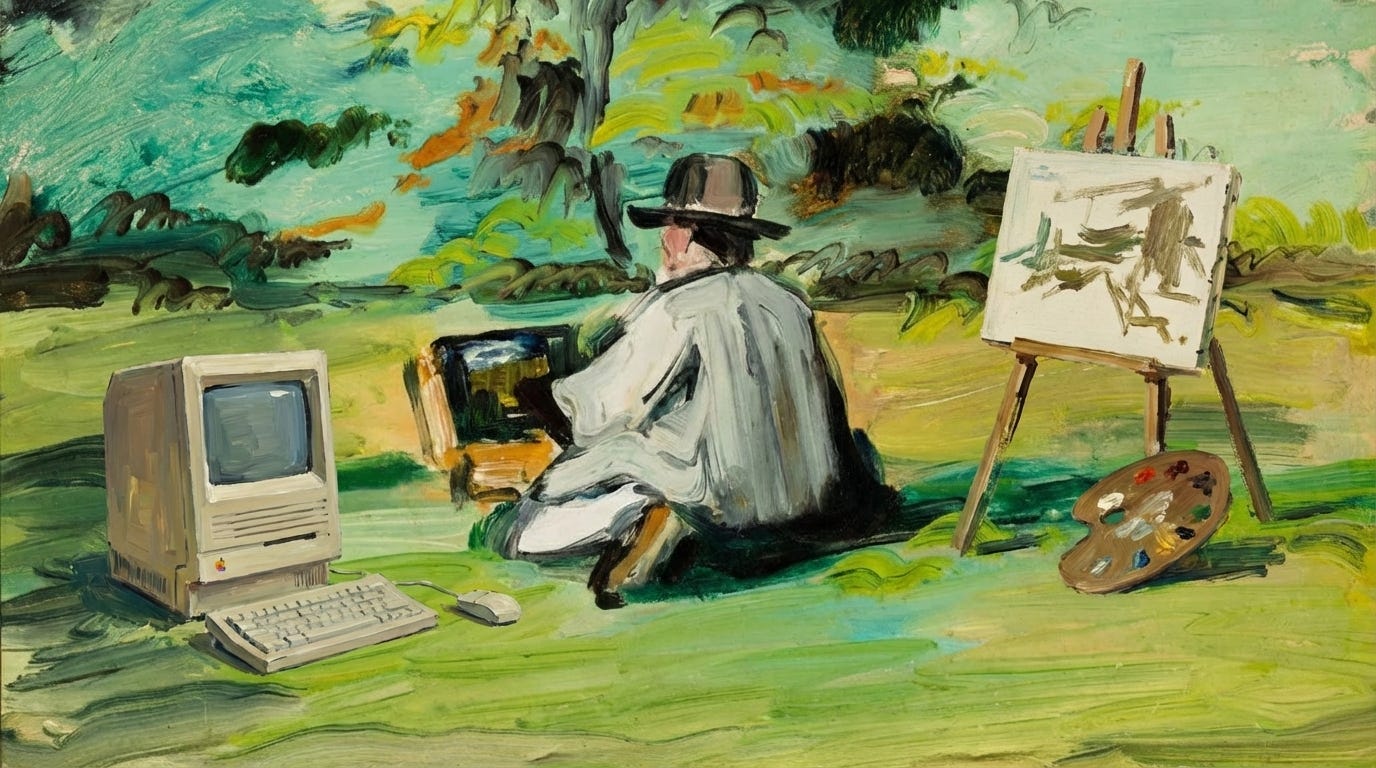

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, when I was learning how to program, one of the most iconic bloggers and tech figures was Paul Graham, the cofounder of the influential startup accelerator Y Combinator, which helped launch startups like Airbnb, Coinbase, Dropbox, and Stripe.

In addition to running Y Combinator, Graham also published essays on his personal website. It was Graham who introduced me to the essay form, if I’m being honest—and his 2003 essay ‘Hackers and Painters’ was particularly formative. If Joan Didion’s packing list showcased an aspirational lifestyle for writers, then Graham’s ‘Hackers and Painters’ did the same for software people.

‘Hackers and Painters’ begins with Graham reflecting on his unconventional education:

When I finished grad school in computer science I went to art school to study painting. A lot of people seemed surprised that someone interested in computers would also be interested in painting. They seemed to think that hacking and painting were very different kinds of work—that hacking was cold, precise, and methodical, and that painting was the frenzied expression of some primal urge.

Both of these images are wrong. Hacking and painting have a lot in common. In fact, of all the different types of people I’ve known, hackers and painters are among the most alike.

What hackers and painters have in common is that they’re both makers. Along with composers, architects, and writers, what hackers and painters are trying to do is make good things. They’re not doing research per se, though if in the course of trying to make good things they discover some new technique, so much the better.3

Graham writes about programming as a creative practice, something akin to a craft. He compares hacking to painting in a way that ennobles both, arguing that they have equivalent intellectual status and symmetric concerns. (In one passage, he writes: ‘Great software…requires a fanatical devotion to beauty. If you look inside good software, you find that parts no one is ever supposed to see are beautiful too…It drives me crazy to see code that's badly indented.’)

And Graham also touches on a problem familiar to artists and writers: ‘There is not much overlap,’ he laments, ‘between the kind of software that makes money and the kind that’s interesting to write.’ What, then, should idealistic young programmers do?

The answer to this problem, in the case of software, is a concept known to nearly all makers: the day job. This phrase began with musicians, who perform at night. More generally, it means that you have one kind of work you do for money, and another for love.

Nearly all makers have day jobs early in their careers. Painters and writers notoriously do. If you’re lucky you can get a day job that’s closely related to your real work.

Which brings us back to the question I posed at the beginning of this newsletter, and the question I had when I began writing my review of Marx’s book for Asterisk—

Who can afford to make art?

If you want to become an artist or writer, there are a few well-trodden paths to do great work without starving. You could, for example:

Inherit wealth. The preferred path for many modernists, like Marcel Proust (who inherited around €4.5 million when his parents passed away) and Gertrude Stein (she and her brother shared a trust fund worth 8,000 francs in 1904).4 The artist Florine Stettheimer also came from a wealthy family, and painted many of her works while living in the luxurious Alwyn Court apartments, one block south of Central Park.5

Marry into wealth. The heroine of Amina Cain’s novel Indelicacy is a cleaner at a museum, until her marriage to a wealthy man—then, finally, she begins to write. But such unions are less common in real life than they are in fiction, as the economist Tyler Cowen observed in the New York Times. And I suspect that many people—especially women raised by highly-educated mothers—are ill-suited to this path. (I have vivid memories of my mother telling me, “Remember, an education is the one thing that no one can ever take away from you.’ The implication was that a partner’s financial support could be.)

Become independently wealthy, and then make your art. This fantasy sustains many highly-paid and nearly burned-out corporate professionals, but as I wrote in December, you should do what you want to do now—even if you only have a few hours a week to pursue your artistic projects.

Cultivate a patron, sugar daddy, or similarly generous benefactor. We wouldn’t have the other Marx’s writing (Karl Marx, Das Kapital) without Friedrich Engels, who was born into a wealthy Wuppertal family and helped Karl with expenses.

But what if you don’t have access to a large pool of life-sustaining capital? Wealth is optional; luck and hard work aren’t. Other paths available to you:

Become an outlier. If you’re a critic, become the voice of your generation—quickly!—so you can get picked up by New Yorker (like Hilton Als, Doreen St. Félix, Jia Tolentino, and Kyle Chayka). If you’re a novelist, become Sally Rooney.

Harness your finances to the art–academic complex. Many artists and writers today make a living as tenure-track professors—or, less promisingly, as precariously employed adjuncts. Others apply to grants and fellowships that will cover their expenses and offer them unfettered time to work (assuming, of course, they’ve lined up more funding for the future). While money is disbursed in an unreliable and unpredictable fashion, it’s not a bad path—as long as major funders, like the National Endowment for the Arts, aren’t affected by politicized budget cuts.

Work a day job. Franz Kafka worked at an insurance firm, and his professional and familial commitments meant that he could only write fiction in the evenings. In Daily Rituals: How Artists Work, Mason Currey includes a letter that Kafka wrote to his fiancée, Felice Bauer, about his schedule:

From 8 to 2 or 2:30 in the office, then lunch till 3 or 3:30, after that sleep in bed (usually only attempts)…till 7:30, then ten miutes of exercises, naked at the open window, then an hour’s walk…then dinner with my family…then at 10:30 (but often not till 11:30) I sit down to write, and I go on, depending on my strength, inclination, and luck, until 1, 2, or 3 o’clock, once even till 6 in the morning.

Poor Kafka never escaped his day job, but many artists and writers strive to. So how do you accomplish that?

Don’t quit your day job…yet

You could take the day-job-to-outlier path, like the great postmodernist writer Thomas Pynchon did in the 1960s. Pynchon entered college as an engineering major and left as an English major. Afterwards, he spent 2 years working for Boeing as a technical writer while writing his debut novel, V., which was published in 1963. It was successful enough that he could quit his job and, it seems, live cheaply and write full-time.

Or you could take the day-job-to-outlier-and-academic path, which the renowned fiction writer and teacher George Saunders did in the 1990s. Saunders studied engineering in undergrad, and then got his MFA in creative writing in 1988. He then worked as a geophysicist and technical writer until 1997, when his literary success led to a faculty position at the same MFA program he graduated from.

But researching my Asterisk essay led me to believe that these 20th-century success stories are harder to achieve in the 21st century. It’s worth taking a look at a more contemporary example—the sci-fi writer Ted Chiang. Like Pynchon, he worked as a technical writer (for Microsoft); like George Saunders, he’s a celebrated short story writer. By the time Joshua Rothman profiled him for the New Yorker, in 2017, Chiang had won ‘twenty-seven major sci-fi awards,’ including four Nebulas and four Hugos. The film Arrival, which was based on one of Chiang’s stories, had premiered in theatres a few months earlier, and went on to make $203 million at the box office.

But despite all of Chiang’s successes, the profile noted that:

He still works as a technical writer—he creates reference materials for programmers—and lives in Bellevue, near Seattle…

Chiang continues to make ends meet through technical writing; it’s unclear whether the success of “Arrival” could change that, or even whether he would desire such a change.

And in 2019, in an interview with The Believer, Chiang expressed doubts about whether he would ever be able to escape his day job:

Are you still working as a technical writer on the side?

Right now I am able to take a break from that. But I’m under no illusion that this is a permanent situation.

Has the increased interest in adapting your work into film offered more opportunities?

That’s not a reliable source of income. The odds of anything coming from that are just so long.

Chiang isn’t alone. In 2023, the journalist Kate Dwyer asked, ‘Has it ever been harder to make a living as an author?’ One of the novelists she spoke to was Andrew Lipstein, who works as a product designer at Robinhood:

In early August, after Andrew Lipstein published The Vegan, his sophomore novel, a handful of loved ones asked if he planned to quit his day job in product design at a large financial technology company. Despite having published two books with the prestigious literary imprint Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Lipstein didn’t have any plans to quit; he considers product design to be his “career,” and he wouldn’t be able to support his growing family exclusively on the income from writing novels. “I feel disappointed having to tell people that because it sort of seems like a mark of success,” he said. “If I’m not just supporting myself by writing, to those who don’t know the reality of it, it seems like it’s a failure in some way.”

And then there’s the journalist Teddy (T.M.) Brown, who regularly writes for the New Yorker and the NYT Style Magazine…while working a day job in B2B SAAS. In a newsletter from last year, ‘You’re going to be tired either way’, he wrote:

I’m writing this in the 20-minute blocks I have to spare between meetings at my day job…The nice thing about having a day job is that I have the financial breathing room to pitch stories I actually want to write about. But the probably annoying truth about my setup is that I work a lot…

You have to want it really badly. It’s the advice I give to younger writers who ask how I maintain both sides of my life. You have to take stock of what you want from your career and what you want your life to look like and base it against a 24-hour clock that only moves in one relentless direction.

Day jobs can inform one’s creative practice, as my friend Megan Marz observed in The Baffler. Reviewing an exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art (which was later presented at the Cantor Arts Center in the Bay Area), Marz noted that Frank Stella was a house painter, Vivian Maier a nanny, Barbara Kruger a designer for Condé Nast. The overall message of the exhibition is optimistic—maybe your day job is the reason your art is so good! And yet:

Here were a bunch of exceptional individuals…Here were seductively narrow spotlights beamed on inflection point after inflection point at which a creative mind had turned this valuable material, a job, into art. So many spotlights make a halo, or maybe a mirage. I wanted a job, too, until I remembered I already had one.

In the end, the art in Day Jobs is not demystified by its source material as much as the day jobs are remystified by artistic success. The only way for this effect not to have occurred might have been to show unfinished, unrealized, or nonexistent art: what artists couldn’t quite bring to completion, or couldn’t even start, because they were too busy with, or tired from, their jobs.

Dignified working conditions are disappearing

A day job can complement one’s artistic practice—assuming, of course, that it:

Lets you commercialize the same skills you’re honing for your artistic work

Makes enough money to pay your rent, offer you psychological security, and pay for artistic expenses (classes, materials, &c)

Takes up a tolerable amount of time, so you can still spend mornings/evenings/weekends on your own work

But it’s hard to achieve this. In March of last year, Steven Kurutz wrote a NYT article about the struggles that Gen Xers in creative fields were facing:

If you entered media or image-making in the ’90s — magazine publishing, newspaper journalism, photography, graphic design, advertising, music, film, TV — there’s a good chance that you are now doing something else for work. That’s because those industries have shrunk or transformed themselves radically, shutting out those whose skills were once in high demand…

“I am having conversations every day with people whose careers are sort of over,” said Chris Wilcha, a 53-year-old film and TV director in Los Angeles…“My peers, friends and I continue to navigate the unforeseen obsolescence of the career paths we chose in our early 20s…The skills you cultivated, the craft you honed — it’s just gone. It’s startling…”

In the mid-2000s, he made a devil’s bargain for someone who grew up on punk rock: He started shooting commercials for Chevrolet, Facebook and Apple, among other companies, to support his family and fund his passion, documentary films…Then came a plot twist. Those commercial jobs grew scarce because of the consolidation of ad agencies and the rise of marketing content plucked from social media…

“Now it’s a knife fight for every job,” he said. “The cruel irony is, the thing I perceived as the sellout move is in free-fall.”

It’s worth noting that these problems don’t just affect Gen X. Zoomers emerging onto the labor market are also struggling to find a ‘safe’ day job that might facilitate their artistic ambitions. A few weeks before Kurutz’s article was published, the economic commentator and creator kyla scanlon argued that Gen Z is facing the end of predictable progress and career security.

‘Gen Z,’ Scanlon writes, ‘faces a double disruption: AI-driven technological change and institutional instability.’ Instead of criticizing certain ambitions as irrational (like trying to make it as a content creator), she suggests that they represent young people ‘responding rationally to a world where traditional “safe” choices feel increasingly risky.’

A creator with the right viral moment can generate more wealth in a week than their parents saw in a year. A lucky crypto trade can outperform a decade (or two) of traditional saving. The paths to wealth have been reimagined, to say the least and it feels like the in-between is disappearing.

And as the ideal day job becomes more and more scarce, artists and writers are facing another threat:

The housing theory of everything

In an earlier draft of my Asterisk essay, I wrote:

Complaints about cultural decline tend to be very vibes-based, so I’m going to try to investigate it using a classic technique from that other Marx: historical materialism. If you’re more liberal than left, don’t worry—we can also call this, for YIMBY readers, ‘the housing theory of everything.’

It felt a little sad to cut these lines—they just didn’t fit into my final draft!—but I’m introducing them here so that a) I can practice zero-waste writing, and b) so I can bring up the housing theory of everything, from a 2021 essay in Works in Progress.

The authors—John Myers, Ben Southwood, and Sam Bowman—note that housing has become extraordinarily expensive in the last 40 years, especially in cities that were historically centers of artistic and literary innovation:

Average New York City metropolitan area house prices are up 706% since 1980 (or 376% more than US consumer prices, and 326% more than US wages). For San Francisco the rise is 932%. London house prices are up over 2,100% in that period (or around 1,500% more than wages)…

City dwellers have to spend more money on housing, which might mean less money spent buying books, supporting independent cinema, going to contemporary dance performances…

And it also affects who can afford to live in cities:

Nearly all innovation happens, and has always happened, in cities. Just as cities have vast labour pools that make it easier for workers to find jobs that match their skills, they also allow innovators to collaborate to come up with new ways of doing things. Sometimes cities have experienced bursts of innovative output that changed the world – like Amsterdam in the 17th century, Edinburgh and London in the late 18th to early 19th centuries, Cleveland in the late 19th century, Vienna and Detroit in the early 20th century, and San Francisco today…

By limiting the number of people who can go to live in [cities]…we may also be missing out on the new ideas that drive society forward.

Though Myers, Southwood and Bowman focus on the scientific and technological ideas we may be missing out on, my Asterisk essay proposes that we’re also missing out on significant intellectual and artistic innovation. As the critic and novelist Christine Smallwood observed in her essay, ‘A Reviewer’s Life,’ for The Yale Review:

It is impossible to know what ideas never came into the world because someone couldn’t or wouldn’t accept an hourly rate that barely covers the babysitter.

We’re not just missing out on the capital-W Writing that freelance critics would otherwise do for magazines and literary journals; we’re also missing out on the lowercase-w writing produced for personal blogs and newsletters. The early-aughts internet was shaped by this kind of writing, and it feels, to me, that it’s equally endangered. As the Twitter menswear guy behind two of the most influential men’s fashion blogs of the 2000s, Die, Workwear! and Put This On, observed:6

Bad art (and criticism, and content) comes from bad incentive structures

Writing my Asterisk essay led me to conclude that, when it comes to conversations about artistic stagnation and mediocrity, perhaps the most important thing to think about is the money. Who has it? Who’s making money? Who isn’t? Who’s financially backing unprofitable work? What kind of work is valued by the market? What kind of work isn’t?

W. David Marx’s Blank Space explicitly focuses on cultural conditions. But I personally felt that his anti-poptimist argument—and his analysis of why there’s so much slop in the world—is limited by his lack of engagement with the economic conditions.

Let’s take a look at the economic conditions for writing—and for criticism and journalism, in particular. Here’s another part of an early draft that I had to cut:

“One dollar a word,” the critic and artist James Hannahan observes…“was a good rate in 1953.” According to the BLS’s inflation calculator, this would be equivalent to $12.14 per word today—a rate that no writer I know has ever made.

Why are wages for professional writing so low? I get into this in my essay, using an influential alt-weekly, the Village Voice, as a case study. But essentially:

The Voice…reached its greatest heights under a specific economic model for journalism — one that 21st century technologies have destroyed. When the paper was founded in 1951, it had two sources of revenue: from readers purchasing the paper and classified ads…

But this business model disintegrated with the rise of the internet. In the summer of 2001, a twentysomething Anil Dash began working as a web developer of the Voice…“My third day there, Craigslist launched in New York. I knew. I was like, ‘Oh my god.’” The Voice could no longer sell what Craigslist offered for free.

You probably know the rest of the story. After Craigslist, the deluge…

What happened to journalism in the 21st century is, in many ways, the story of the conflict between two utopian values: Information wants to be free and Writers should be paid.

There’s a lot of money in the production and dissemination of content. It’s just not going to the creators. (Or, in the case of TV shows, it’s not going to the actors.) Numerous decisions—by companies like Google, which penalized publishers in the 2000s for instituting paywalls; by the people behind websites like The Pirate Bay, Sci-Hub, Anna’s Archive; and many others—have created a culture where free information is normal. This isn’t always a bad thing. But we’ve struggled to reckon with the effects of this—many people feel entitled to access information without having to pay for it directly! And other forms of remuneration (ad revenue, government funding) aren’t always available.

And my belief is that this directly impacts the quality and candor of critical writing. One of the most useful articles I read, while researching my Asterisk essay, was Luke Ottenhoff’s ‘Music criticism in the time of stans and haters.’ It’s common to complain that music critics focus too much on pop stars (Taylor Swift, Lana del Rey, and now PC-music-darling-turned-pop-star charli xcx); that they pull their punches and are uselessly positive about everyone; that they don’t write about indie musicians enough.

But the economic and attentional dynamics of the internet are such that freelance music critics are getting paid, let’s say, $100 for a review. If they write a negative review of a pop star, they’ll get harassed online by fans. If they pitch a review of an independent artist, most publications won’t want to take it—unknown names don’t drive traffic.

It might be the case that music critics are more cowardly than they used to be…but I find these other dynamics more usefully explanatory.

And if a publication like Pitchfork decides to paywall their criticism—as they did earlier this month—people often focus on the information readers will lose, and not the income that writers have already lost, and continue to lose, without paywalls and other durable revenue streams:

It’s hard. I don’t know how to resolve the conflict between Information wants to be free and Writers deserve to be paid. But it’s worth noting that the internet of yesteryear, where almost every article was free to read, was also the internet that drastically reduced the value of highly researched, carefully argued writing. That internet helped shape our contemporary attentional landscape, full of bad work, underpaid artists, and antisocial incentives for content creators.

Nostalgia is not a strategy

We should be cautious about idealizing the early, paywall-free internet. But we should also be cautious about idealizing the 20th century. Yes, it offered a better economic model for journalism and criticism. Yes, it was replete with artistic movements (in the first 25 years of the century, as W. David Marx notes, already included ‘fauvism, cubism, futurism, expressionism, Dada, de Stijl, and surrealism’).

But what can nostalgia do for us in the 21st century? Not much, I think, and I don’t have much patience for people plaintively trying to resuscitate an old world. One of the earliest paragraphs I wrote for my Asterisk essay—which I retained, with only minor edits, in the final draft—was this one:

I feel impatient, though, when I encounter yet another essay that pines after the past. Yes, if only we could return to that world — where newspapers raked in ad revenue; where rent was cheap in lower Manhattan; where there were thousands of journalism jobs across the country — then maybe American criticism could be great again. But we can’t revive the past, any more than leftists can bring back postwar trade unions in a globalized economy, or conservatives can bring back 1950s-style traditional marriages in a world where more women have bachelor’s degrees than men.

The economist and PM of Canada, Mark Carney, made a similar point—in relation to geopolitics—at a speech last week in Davos:

And the old order…was it really so ideal? The benefits of the past were unevenly distributed, to put it politely. My mother was born in Hanoi, Vietnam, the same year Thomas Pynchon’s debut novel was published. He spent the next few years living off his book advances and royalties; my mother was sheltering from American bombs. The 1990s were when George Saunders went from MFA graduate to celebrated literary star; but it was also the decade where 4 performance artists had their NEA grants cancelled for depicting sexual themes in their work. All of the artists identified as gay, or incorporated the AIDS crisis into their work. How could they not, when gay artists, writers, and intellectuals were dying in droves—and countless elected officials ignored them?7

The old media ecosystem had higher wages, it’s true; it was also a highly restricted professional landscape that only some could enter into. Artists and writers face different challenges, and different opportunities, each decade. I was thinking of all this when I wrote one of the final paragraphs of my Asterisk piece:

I refuse to believe that more participation leads to a degraded cultural ecosystem. We can’t go back to the past, but that may be a good thing; there were millions of people who were denied full access to the cultural sphere because of their gender or race or sexuality. People who would have never made it into the inner sanctum of American culture — even at a defiantly countercultural publication like the Voice — can now, for the first time in history, publish from anywhere and reach an audience everywhere.

The future is just around the corner

Time, as Teddy (T.M.) Brown noted, ‘only moves in one relentless direction.’ The future of art and literature won’t be found by resurrecting the past—though learning from the past is always useful.

In an earlier draft of my essay, I wrote:

We’re already living in interesting times. I’d like to live in artistically interesting times, too.

If we assume—as my Asterisk essay argues—that artistic innovation requires adequate-to-beneficient economic conditions for artists—then how can we develop them? Lately, I’ve started to think that there are 2 3 fronts for this problem:

Defending against, and avoid, the degradation of existing conditions. Advocate for higher wages from existing publications. Unionize. Collectively bargain for better pay and benefits. This is essential, and when it comes to criticism and journalism, organizations like the Freelance Solidarity Project play an essential role. That’s why I signed onto their statement on industry-wide cuts to criticism, alongside many writers I’ve admired and read for years. But this isn’t enough, I think, to significantly alter the economic conditions that artists and writers are operating in today. Which is why, I think, there’s a second front:

Create new ways for artists to make money. I’ve previously written about how to expand the market for literature (and literary criticism); the intention here is to ensure that more attention and economic resources are drawn into artistic and cultural milieus, so that important work can be adequately resourced, funded, and paid for. I’m also profoundly energized and excited by the work that Yancey Strickler is doing here. Strickler is a former music critic who founded Kickstarter (which I consider a significant innovation in how creative work is funded), reincorporated the company as a public benefit corporation, and then founded a new company called Metalabel—which has explicitly built in features like revenue sharing to make artistic collaborations more equitable. In 2025, Strickler announced that his new project is developing the legal infrastructure for something called an A-Corp, to offer artists and independent creatives more ways to make money. Strickler and the artist Joshua Citarella have an excellent podcast where they discuss A-Corps and other ways that artists can earn a living and do ambitious work in the world we actually live in, not in some idealized past:

Cultivate publics with ambitious, discerning taste. I added this after an insightful comment from Kristine Benoit de Bykhovetz:

Even with better funding models, we still need publics who have the habits to seek out difficult work, reread, tolerate ambiguity, and reward risk. Otherwise new money just amplifies the same attention incentives. So yes to the two fronts you name, and I would add a third: rebuilding the conditions where attention and discernment are actually cultivated.

Her own newsletter, The Reflective Eye, is an excellent example of how such publics can approach ‘difficult’ art, film, and literature.

The work will happen anyway

A few weeks after I filed my final draft, I came across an essay by the writer Apoorva Tadepalli in The Point, where she writes about literary careerism and the difficulties of a writing life.

The difficulties are numerous—as I’ve spent the last 7,000 words exploring—and yet. Writers write. Artists make art. The work happens anyway. Why? ‘Here’s the thing,’ Tadepalli says:

We (by which I mean writers who are early-career, low-paid, freelance, unknown, whatever) know all about nepotism and backdoor agreements. We know about exploitation, about agonizing over concealing just how desperate we are, about holding our own in negotiating our rates if we even have the privilege to negotiate. We know about having a million side gigs. We know about spending so much time on a five-hundred-dollar article that we can’t bear to try to calculate how much we made per hour of work. And it doesn’t matter to us. It’s frustrating and tiresome, and it matters in the way student debt and seven years earning minimum wage matter, making a difference to where we live and how we eat and what we do at night. But it does not matter to the fact of our actual writing, to the fact that we write, to the thoughts we wrestle with when we read books and try to translate those thoughts into words on a page…We gripe in our support groups, but we still write. We know all the reasons and more why the writing life isn’t worth it, and clearly none of them really matter because we still write.

Artistic work still happens, even in dispiriting economic and cultural conditions. But the counterfactual still plagues me. Maybe we could have more work, better work, work from more of society, representing more subjectivities—if we could only organize and innovate our way to better conditions.

That’s the challenge of the coming decades, and it’s a difficult one, but I think it’s exciting to face difficult challenges, and see if we are worthy of them—no? Digital technologies have largely solved the distribution problem for creatives; but they have not yet solved the monetization problem.

I wouldn’t have the interests I have, nor the opportunities to pursue them, nor the friends and interlocutors and collaborators to work with, without the internet. I want to know if a better internet is possible. Let’s find out together.

Four recent favorites

The only gourmand (perfume) I’ve ever loved ✦✧ Energetic, dreamy breakbeat from a South Korean producer ✦✧ ‘Nothing is happening in San Francisco’ ✦✧ Mia Forrest’s ikebana collages

The only gourmand I’ve ever loved ✦

I line-edited this newsletter while wearing Saffron Flour—a lovely, indulgent fragrance from indie perfumer Courtney Rafuse’s Universal Flowering. I bought the 13-scent discovery set a few weeks ago

I love the smell of saffron—the intoxicating collision between a densely sweet, spicy, cut through with the bright, heady grassy freshness that gives saffron a kind of unusually striking pungency. I got a sample of Baccarat Rouge 540 partly for the saffron, but.

But I prefer the even-temperedness of Universal Flowering’s Saffron Flour—the earliest notes feel more pristine and bright, and the scent settles down into a smooth, gentle lactonic sweetness (whereas Baccarat Rouge 540 becomes almost stiflingly sweet at the end).

Energetic, dreamy breakbeat from a South Korean producer ✦

In 2024, my new year’s resolution was to have an anti-algorithmic year of music discovery. As I wrote in my newsletter:

Some of this is a reaction to hitting peak Spotify: it’s no longer interesting to see what Spotify wants me to Discover, Weekly—especially when it’s reflected back to me, in my end-of-year Wrapped, as a supposedly privileged insight into my taste.

In the last 2 years, I’ve mostly discovered music through friends like Vincent Jenewein. His newsletter about the best electronic music of 2025 introduced me to the infinitely exciting, ebullient, exuberant South Korean producer Yetsuby. Here’s my favorite track from her debut album 4EVA:

The writer Philip Sherburne (who writes an experimental/electronic music newsletter called Futurism Restated) also wrote a great review of the album 4EVA in Pitchfork:

Seoul producer Yetsuby’s music…is a jumble of brightly colored baubles: marbles and beach glass, sequins and gumdrops, all spun into mesmerizingly symmetrical abstractions. You might be momentarily reminded of Hiroshi Yoshimura, Steve Reich, ’90s ambient, and fantastical video-game soundtracks, yet the references float by so gently and swiftly that you’re too swept up in the downy tumult to think too closely about them…

“Aestheti-Q” rides a brisk, syncopated drum pattern and a barrage of monosyllabic vocal samples fashioned into a hiccuping arpeggio…what stands out [in the album] is the high-def quality of her production…Crystalline sounds come in waves, a gentle juggernaut of prismatic streamers and laser zaps—Jersey club reimagined as a geyser of diamonds.

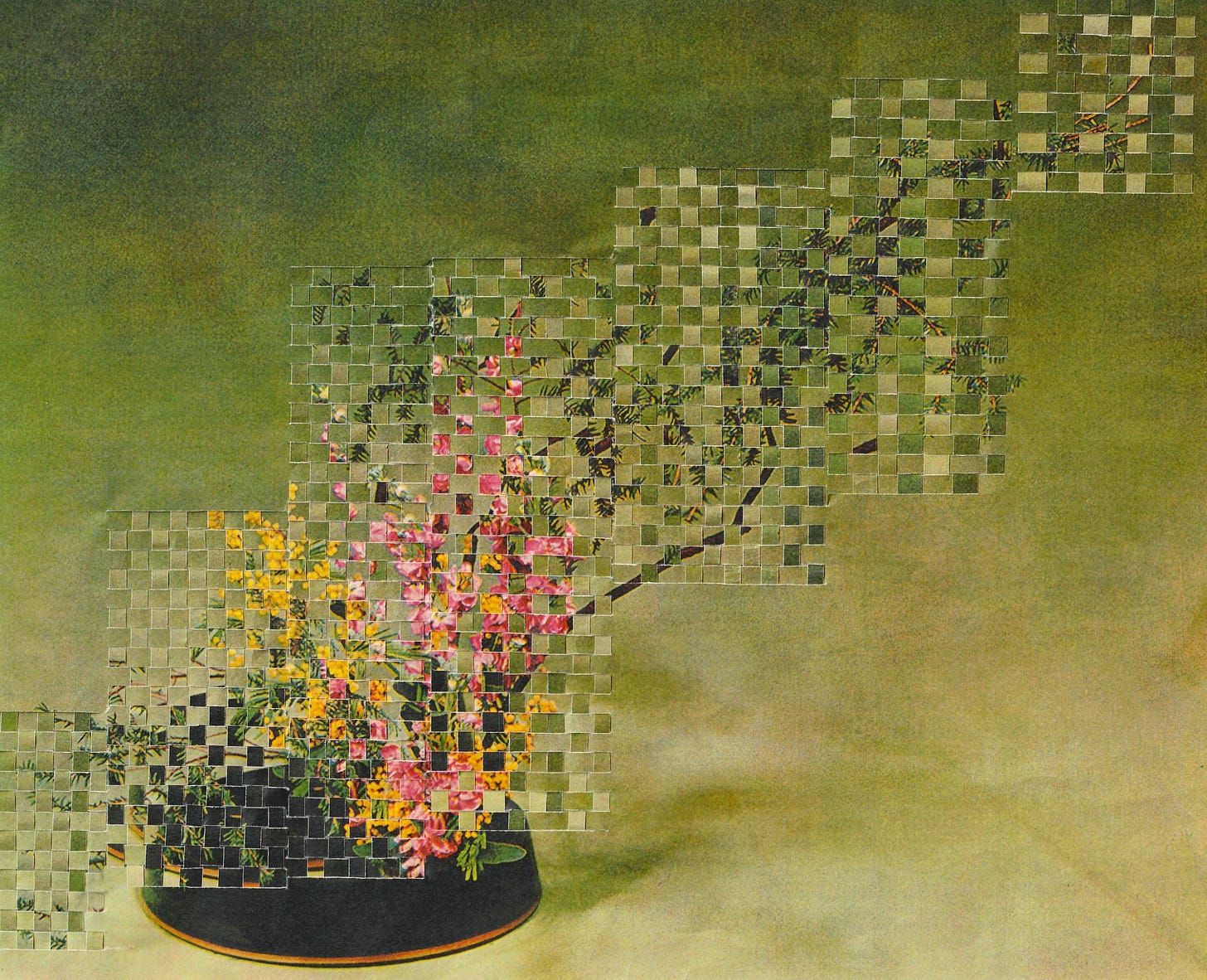

Mia Forrest’s cut-and-woven ikebana collages ✦

The Australian artist Mia Forrest’s ‘Cut Flowers’ project uses images from Shōzō Satō’s 1966 book, The Art of Arranging Flowers: A Complete Guide to Japanese Ikebana, and transforms them using a precise cutting-and-weaving technique:

‘Nothing is happening in San Francisco’ ✦

Earlier this year, the esteemed San Francisco–based publisher McSweeney’s posted a screenshot on Instagram:

Nothing is happening in San Francisco. All the artists are dead. There are no books being made here. The world’s best bookstores are not here. There are no readings, no music venues, no art galleries, no libraries, no orchestras, no museums, no festivals that involve pianos in botanical flower gardens, and no food. There are definitely not poetry readings or theaters or handmade modernist saunas with views of the Golden Gate Bridge. There is absolutely no culture. Don’t even think about moving, or even visiting, here. It’s really terrible. If you do come, you will regret it. If you already live here, like we do, our sincere condolences.

This cheeky narrative of decline was meant to announce San Francisco is Dead, a calendar of literary, film, art, and music events in the city.

I recommend this March performance at The Lab (tickets are free!) featuring the artist and experimental music performer Evicshen, who I’ve written about before—

— and Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste, who did the sound design for a performance involving the poet Claudia Rankine’s work a few years ago. (Here’s a New York Times article about it.)

If you’ve made it to the end of this newsletter, I’m touched. There are thousands of posts you could be reading, instead of mine—thank you for your attention and time! And if you enjoyed this post, please share it with a friend:

I’ll be back in your inbox shortly with everything i read in january 2026, feat. mini-reviews of James Joyce’s short story collection Dubliners, the Chinese philosophical classic Zhuangzi, Sarah Schulman’s new book on community and solidarity, and effusive praise for a very good, very new self-help book!

One of the most concise critiques of effective altruism I’ve ever seen comes from Brunella Tipismana Urbano, who recently tweeted:

One of the genius ideas of EA was that it gave a clean procedural answer to a very 2010s ambient anxiety (“how do you live in a world saturated with suffering and inequality? what do you do?”) while also letting you stay legible to the elite and still giving you access to it…but the mood has shifted…we're about to learn what utilitarian optimization without the constraint of morality looks like.

For fans of Rick Perlstein’s magisterial histories of the American right-wing (Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America is one of the best nonfiction books I’ve ever read, and the novelist Lincoln Michel also wrote about it recently)…you may be touched to read about how Perlstein and Aaron Swartz became friends, in a blog post by Henry Farrell:

People who didn’t know Aaron remember him for his tireless work for a variety of public causes. They usually don’t realize that this work went together with a myriad of private kindnesses. I got to know Aaron as an extraordinarily intelligent commentator on Crooked Timber, an academic blog that I contribute to. At first, I didn’t know about the other great things that he had done; he didn’t talk about them unless he was pressed.

He privately helped many other people, in equally unfussy ways. Rick Perlstein, the political historian of the rise of the right, is now famous. Before he was well known, Aaron came across his work, realized that he didn’t have a website, and offered to make one for him. Rick was a bit nonplussed to receive so generous an offer from a complete stranger, but quickly realized that Aaron was for real. They became good friends…

His activism went hand-in-hand with a deep commitment to the intellect and to figuring out the world through argument. This could discomfit other activists, since it meant that he often changed his mind. He had the profound intellectual curiosity of a first rate scholar without the self-importance that usually accompanies it.

For people unfamiliar with Paul Graham, there are two other things worth noting.

First, he’s been consistently critical of Trump—while other Silicon Valley figures have chosen deference (aka spinelessness; exactly the kind of spinelessness that visionary thinkers and maverick intellects are not supposed to exhibit…) In October 2024, Graham encouraged people to vote for Harris, noting that Trump ‘ran the White House like a mob boss, choosing subordinates for loyalty rather than ability. No one knows that better than the people who worked for him.’ In April 2025—four months into Trump’s second term—he tweeted that a startup founder (who had voted for Trump) told him, ‘You were so right.’

Second, he’s one of the rare tech figures to publicly support Palestinians during the genocide. Another is the Replit founder and CEO Amjad Masad. In the SF Standard’s profile of Masad, Graham said:

There are a lot of people who care about the Palestinians but who are afraid to speak out publicly,…What Amjad and I have in common is that we don’t have to worry about being fired if we do.

Others do—like Paul Biggar, who cofounded CircleCI and was fired from the company’s board after writing a blog post about how disappointed he was by his peers:

The propaganda kills me…So much humanity for those killed on October 7, none for the people killed on the 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, or in November or December. 20,000 people, killed by deliberate, indiscriminate bombing.

None either for the people killed on Oct 6, 5, 4. For the people massacred in 1948 and since. No protest of the illegal occupation, the illegal settlements. The razing of the villages and the olive groves. They don’t exist to them; they didn’t happen.

The blog post has comprehensive citations for the deaths he mentions, which I’ve omitted here. After he was removed from the board, Biggar posted on Mastodon: ‘Actions have consequences, and that’s ok.’

I originally used this calculator to convert the Stein trust fund to 2026, and wrote that the Steins had a trust fund of

8,000 francs in 1904, or about €3.5 million today.

But David Barry helpfully pointed out in a comment that it doesn’t account for the 1960 redenomination! According to the more precise INSEE calculator, their trust fund would be worth only €36,900 today.

Writers unburdened by familial wealth might appreciate Emily Cookie’s funny, frank, and insightful ‘Pay to Play,’ published in Bookforum:

The few writers I knew who hadn’t gone to fancy schools could be spotted because their careers were advancing more slowly, as mine was. I would have been so much better at everything, I thought, if I had been raised in a family with more money—until, in a feat of self-help, I began to insist to myself that the reverse was true. It was better to have come from less, I decided; it was both more interesting and undoubtedly purer to be poorer. I soon started applying these upside-down values to everything: I preferred dysfunctional organizations, friends who showed up late, skin with wrinkles, the unsuccessful, the awkward, the backward, the ill. The correctness of these renovated judgments seemed so clear, and I held to my new beliefs so doggedly, that I was surprised every time I encountered someone who didn’t agree, someone who professed to appreciate success, grace, timeliness, health.

Cooke doesn’t dismiss the influence of wealth, but she also points out that writing has always had—will always have—some level of meritocracy:

Having lots of money confers status but having very little confers legitimacy, which offers a different kind of status; having too much is unseemly yet so is having none. The rich and the poor collude in believing that the amount of money you inherit or make means something about your moral fiber, the quality of your art. What will we do when we find out it doesn’t?

Many years ago, I made a tumblr to write about fashion and personal style. Derek Guy followed me, and I instantly developed so much performance anxiety and fear that I never posted again.

I’m sorry to lib out in this paragraph, but also: surely there’s no better time to lib out than now? I’m so sick of our current political climate!

This is such a helpful framing. I agree that economics and infrastructure are upstream of what kind of art and criticism can exist. But I keep wondering about a second upstream variable: the formation of taste. Even with better funding models, we still need publics who have the habits to seek out difficult work, reread, tolerate ambiguity, and reward risk. Otherwise new money just amplifies the same attention incentives. So yes to the two fronts you name, and I would add a third: rebuilding the conditions where attention and discernment are actually cultivated.

So much to ponder, but here is a thought off the top of my head about resolving the dilemma between "information wants to be free" and "writers deserve to be paid":

Something heartening I've seen here at Substack and in other parts of the internet are the writers who are making a making a full-time income, or a decent side income, thanks to the patronage model. Of course, this isn't the most stable model and it requires a lot of work upfront if it's ever to succeed (hence why you rarely see it recommended as a viable path in the creator economy). BUT. It's a real thing. There are people out there (including me) who are spending more money each year on supporting creators they care about than they do on Netflix. I guess that's unusual, but unusual is okay: the Pareto principle, or some form of it, seems to be the norm when it comes to source of income. A few generous donors, and a slightly larger amount of mini-donors/fans, can make all the difference and allow everyone else to read for free and help the writer grow by word of mouth. You probably won't be rich if you follow this path, but you'll have your basic needs met, which is what matters most to most of us writers.

PS. Of course, it's easy to argue that we don't see a lot of examples of the patronage model and therefore it's not truly viable etc., but the fact that we _do_ see it means that it's possible. And with things constantly changing and evolving and finding their footing, I like to stay hopeful.